In Part 1 we traced basketball’s early history culminating in Hank Luisetti and Kenny Sailors’ historic appearances in New York’s Madison Square Garden where they challenged the orthodoxy of the day by shooting one-handed while airborne. In Part II, we’ll explore the evolution of shooting styles in greater detail and show how the modern jump shot transformed basketball in four key ways.

Continue reading…Author Archives: Mark Seeberg

A jump shot is better than a layup

When I launched my blog in 2014, I outlined ten immutable laws or principles that define the nature of basketball and govern its play. These laws are fundamental to understanding, coaching, and playing basketball. Once mastered they form a prism through which one can “see” the game, appreciate its simplicity, and master its subtleties. At the center of the ten is the all-important Fifth Law: A jump shot is better than a layup. For me it’s the cornerstone on which modern basketball theory rests and why I named my site better than a layup. Over the next few weeks, I’ll unpack this law in a series of three posts. Here’s Part I.

Continue reading…Records are made to be broken, but…

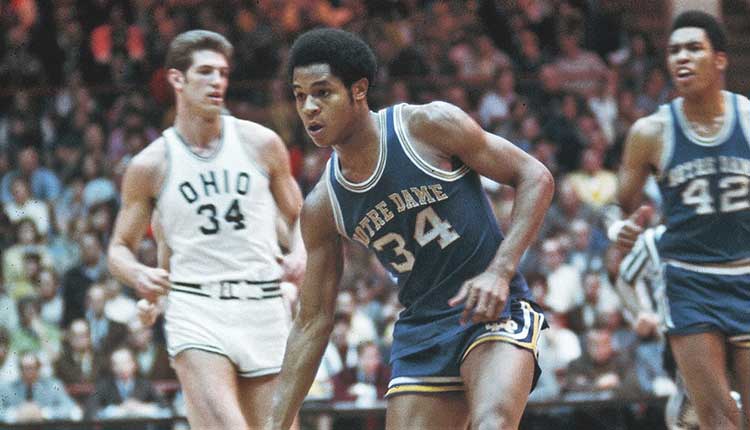

Though the 82nd NCAA Tournament has been scrubbed, we can still celebrate the 50th anniversary of Austin Carr’s single-game scoring record: 61 points in the 1969-70 first round game against Ohio University, the Mid-American Conference champion.

Shooting 57% from the field, the 6’3” Notre Dame guard made 25 field goals out of 44 attempts. He nearly duplicated this amazing feat a week later against SEC champion Kentucky and Big Ten champ Iowa scoring 52 and 45 points respectively. His three-game shooting percentage was 58%.

Significantly, he was joined by teammate Collis Jones who averaged 23 points per game in the three contests. Together, they produced 228 points in three successive tournament games — an average of 76 points per game on 54% marksmanship.

For a detailed look at their amazing feat I invite you to visit the piece I posted last week at Hudl.com. You’ll find a highlight film of their two-man, single-game scoring record (85 points) as well as an intriguing comparison with last year’s tournament field.

If you’re interested in seeing the entire game, visit my YouTube channel. Digitized from an ancient Sony reel-to-reel video tape, the game is not only great fun to watch, but is of historic interest as it marks the beginning of the end of one era in college basketball and the launching of the one we now experience. In many ways, it foreshadows how the college game evolved as it grew in popularity, driven by 24/7 cable coverage and the explosion of March Madness.

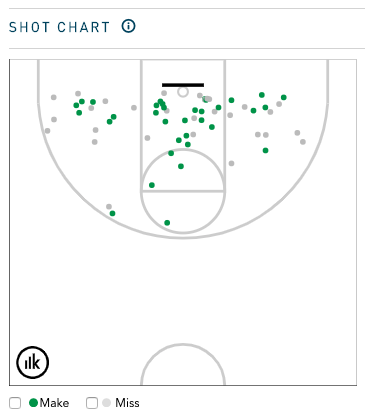

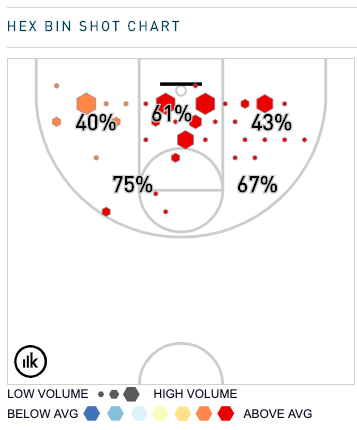

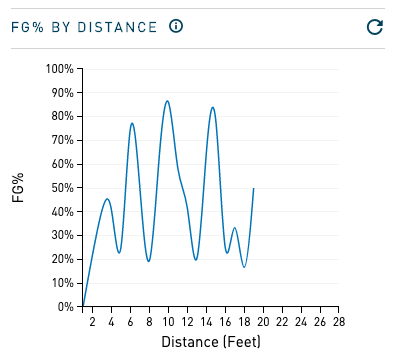

In the meantime, here are several Krossover charts I constructed to bring analytic definition to the Carr-Jones record, all of it occurring in an era before the 3-point shot.

Chart #1: Traditional Shot Chart: 63 FGA, 34 FG, 54%

Chart #2: Hot Zone: The Hex Bin Shot Chart shows volume by hexagon size and efficiency by color.

Chart #3: FG% by Distance

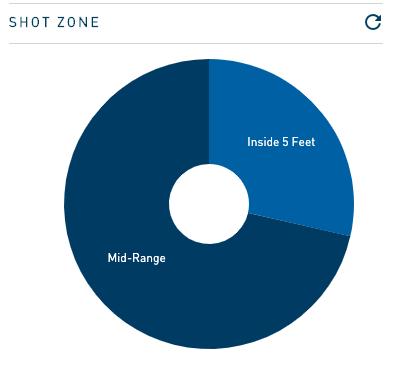

Chart #4: Shot Zone: Midrange: 40 FGA, 20 FG, 50%; Inside 5 Feet: 23 FGA, 14 FG, 61%

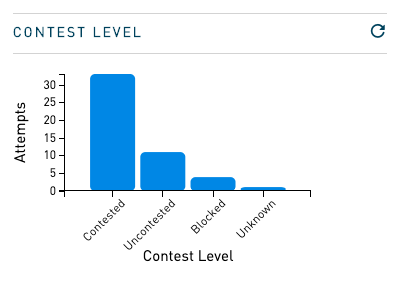

Chart #5: Defensive Contesting Level: Contested: 40 FGA, 22 FG, 55%; Uncontested: 17 FGA, 10 FG, 59%; Blocked: 6 FGA, 0 FG, 0%; Unknown: 2 FGA, 2 FG, 100%

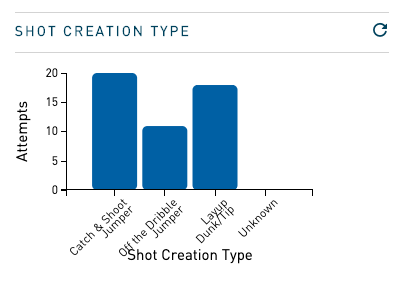

Chart #6: Shot Creation Type: Catch & Shoot Jumpers: 23 FGA, 9 FG, 39%; Off the Dribble Jumpers: 12 FGA,8 FG, 67%; Layup, Dunk, Tip: 27 FGA, 16 FG, 59%; Unknown: 1 FGA, 1 FG, 100%

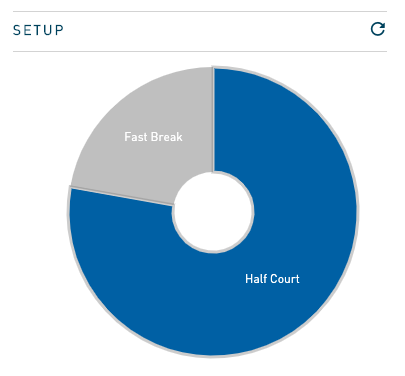

Chart #7: Offensive Set Up: Half Ct Offense: 42 FGA, 24 FG, 49%; Fast Break: 14 FGA, 10 FG, 71%

Keep It Binary, Stupid

Basketball unfolds as a series of choices, one leading to the next. No matter how controlled or patterned a team attempts to be, the offensive scheme will inevitably break down requiring the attackers to improvise.

Effective coaching exploits this reality by placing players in spots where their natural freelance abilities come to the fore and where the choices are binary – “either/or” situations where it is relatively easy for the offense to read the defense and act quickly.

Complicated offensive schemes that congest the floor, obscure the choices, and attempt to control too many variables reward the defense by creating uncertainty and indecisiveness. Too many moving parts complicate the reads, granting the defense time to react.

Conversely, offenses that create quick, binary decision-making are built around actions and maneuvers that shorten defensive reaction time. Effective offense reduces the number of choices by forcing defenders into “no-win” situations where a choice to respond in one way renders them vulnerable in another way. This makes it easier for offensive players to see or read the defense and seize the initiative quickly.

Basketball’s fourth law – Keep It Binary, Stupid – explores these principles.

The New 3-Point Line is a Bust

When I finally tuned in there were less than ten minutes to play.

9:35 to be exact.

Kentucky’s Johnny Juzang had just knocked in a 3-pointer to increase the Wildcat’s meager lead to eight, 58-50. Twenty-four seconds later, Texas Tech missed a jumper, foreshadowing the utterly dreadful nine minutes of basketball that were about to unfold.

Eventually, Kentucky pulled out a 76-74 victory in overtime but I never got that far. The final minutes of regulation play were enough for me. In all, 4 field goals, 10 turnovers, 10 fouls.

On average, over the course of nearly ten minutes of play, two top-20 teams, representing premier D-1 programs with access to the best recruits in the country, collectively generated one basket every two minutes and forty seconds of play. Yikes!

Ten seconds after a timeout at the 1:11 mark, the Wildcat’s Tyrese Maxey missed a quick jumper and was promptly criticized by ESPN’s Jimmy Dykes. “Not a good shot… you gotta run some offense.”

“Jimmy,” I shouted at the screen, “I’ve watched Kentucky ‘run offense’ for the last nine minutes and nothing good has happened.”

When your offense produces one basket on seven shot attempts during the final quarter of play – that’s roughly a field goal attempt every 1 minute and 43 seconds – there’s not much benefit to “running some offense.” You might as well jack it up and hope that by increasing your attempts something eventually goes in.

For their part, Texas Tech didn’t fare much better. During those final 9:35 they went 3 for 12 from the field, only catching Kentucky as regulation expired on the back of seven free throws.

Look, I get it.

Every team has an off night or stretches in a game when the wheels come off. And lots of time, the bad play becomes infectious, one team dragging its opponent into the mire. Last Saturday’s game between 15th ranked Kentucky and 18th ranked Texas Tech is neither indicative of their true prowess or representative of the state of college basketball this season… but it’s not far off, either.

We began this season with coaches, commentators, and fans all asking the same question: how will college basketball’s new 3-point line affect the game?

Will extending the line to the international distance of 22 feet, 1¾ inches curb the game’s growing emphasis on the 3-pointer, leading to greater variety in offensive style and strategy as the NCAA intends? Will shooting percentages at the longer distance remain sufficient to pull defenders even farther from the basket, opening the floor for more dribble drives and offensive maneuvers inside the arc? Will players who lack long-range proficiency rediscover the value of the post up and short range jumpers?

With two-thirds of the season behind us we can reach some tentative conclusions.

Continue reading…