So, finally… why is a jump shot better than a layup?

Three reasons.

First, jump shots are easier and quicker to generate. It takes less time to create a “decent” jumper than a “perfect” layup, and frequency – what hockey folks call “shots on goal” – means a lot. It’s the great equalizer. A team that takes more jump shots can outscore a team that takes fewer shots even if it makes baskets at a poorer percentage rate.

Second, efficient jump shooting stretches the defense, opening pathways to the rim. Teams unable to threaten the defense with the jump shot have less room to maneuver and generally struggle to generate layups. The irony is that good jump shooting – shot attempts “far from the basket” – leads to layups or shot attempts “close to the basket.”

Third, jump shooting promotes simplicity, leading to fewer turnovers and empty possessions. It doesn’t take a complicated offense or intricate play to free a teammate for a quality jump shot. Coaches and television commentators endlessly preach the importance of making the “extra pass.” But is an offense featuring multiple passes before a shot attempt inherently more effective than one that features fewer passes? A quality shot is a quality shot regardless of how many passes led to it. Conversely, a bad shot is a bad shot. In fact, one might reasonably argue that offensive maneuvers that generate quality shots quickly and more simply – with fewer passes – are preferred because there’s less chance of turnover. Think about it. By definition an “extra” pass is just that – extra, unnecessary, not needed. Modern offenses built to harness the power of the jump shot are simple in nature and create more opportunities to score.

Let’s drill deeper, exploring the backend of our proposition first… the layup.

In modern analytic parlance, layups are “shots at the rim” -– tip-ins, put backs, dunks, and old-fashioned layups. Under game conditions, they are highly accurate and efficient, but hard to come by… less the result of perfectly executed set plays, more the result of freelance maneuvers in the open floor typified by the helter-skelter of transition during the first 10 seconds of possession when the defense is not yet set:

• an errant dribble or pass leading to a steal and quick score;

• a fast break after a defensive rebound or an opponent’s score, resulting in a numbers advantage in the front court;

• a press attack that invites a defensive trap in the backcourt to gain a numbers advantage in the front court.

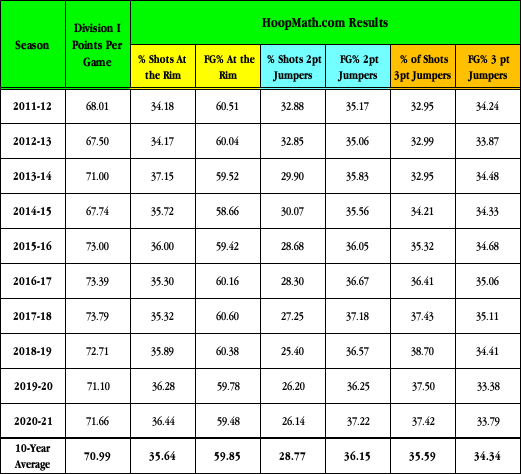

According to analytics guru, Jeff Haley, over the last ten seasons roughly 36% of all field goal attempts in a typical game were “shots at the rim,” resulting in baskets 60% of the time. The remaining 64% of field goal attempts were jump shots from other points on the floor.

Not surprising, during transition – the first 10 seconds of possession when the defense is more likely to be confused and outmanned – nearly 50% of attempts were taken “at the rim” and converted at a 65% clip.

Haley notes that during transition shot attempts are strongly influenced by how a team takes control of the ball. “After stealing a ball, teams generally go to the rim. 70% of all attempted shots in the first 5 seconds after a steal occur at the rim. 40% of all shots that occur in the first 5 seconds after an opponent miss are attempted at the rim, while roughly 30% of shots attempted in the first 5 seconds after a made basket by an opponent are at the rim. Qualitatively, these results aren’t surprising. Steals often lead to quick layups, while fast breaking off of a rebound generally gives you a better opportunity to get to the bucket than does fast breaking off of a made basket by the opponent.”

But once the transition period of a possession is over, it becomes more difficult to get shots “at the rim” as the defense is now set and most offenses tend to settle into more predictable half court routines. “As the time to the first shot of a possession increases,” reports Haley, “the percentage of initial shots attempted at the rim decreases. 29% of initial shots taken between 10 and 15 seconds after the start of a possession are attempted at the rim, whereas 22% of initial shots taken more than 30 seconds after the start of a possession are at the rim.”

That leads to the front end of our proposition… the jump shot.

After the first 10 seconds of possession, not only do jump shots grow in frequency – accounting for 70 – 80% of attempts – they grow in prominence as they not only generate most of the points an offense scores, they are largely responsible for creating the remaining layups or “at rim” shots an offense takes.

The reality is that layups in the half court seldom occur as the direct result of a designed play or series of planned actions, but haphazardly from defensive breakdowns caused by the threat of the modern jump shot.

As we’ve seen, the nature of the jump shot creates gravity… it pulls defenders away from the basket and opens the floor, creating more space for the offense to maneuver. The threat of a quick “catch and shoot” forces the defender to concede an open shot or move closer to contest the potential shooter. If he moves too close or too aggressively, he surrenders precious reaction time, leaving him vulnerable to a sudden change of direction before the catch or a shot fake and penetrating drive after the catch.

Consequently, an offense most likely to produce layups is actually one that encourages jump shooting and is comprised of players who regularly make such shots. If you can free your players for jump shots and claim a decent number of offensive rebounds leading to second shots in the process, you’re likely to outscore an opponent who seeks perfection by running an overly complicated offense in the hopes of springing its players free for uncontested layups.

For example, consider the “Princeton Offense, an offensive system that prides itself on spacing, great passing and cutting, unselfishness, and most importantly, exquisitely timed backdoor cuts to the rim.

Over the years, the school that designed and christened the attack – Princeton University – has made a number of impressive runs in the NCAA tournament despite being outmanned by more talented opponents.

In five seasons spanning 1963 to 1968, they ran off 104 victories, finishing two of the seasons ranked 3rd and 8th nationally, and a third season in 1964-65 advancing to the Final Four led by national player of the year, Bill Bradley. Their performance over the next 26 seasons was more modest, featuring nine trips to the NCAA tournament and eleven Ivy League championships. Then, in 1995-96, they went on a four-year tear, winning 82% of their games, including a 27-2 record in 1997-98 and season-ending AP ranking of 8th in the nation.

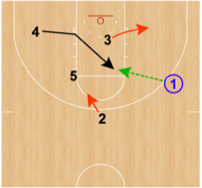

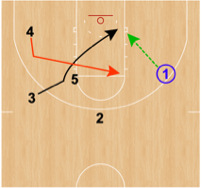

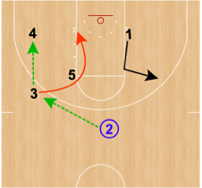

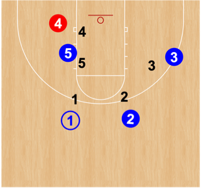

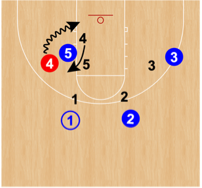

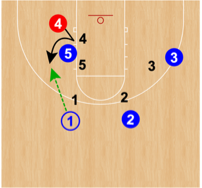

The Princeton attack unfolds in several different ways but often begins in a 2-3 set with all five players stationed above the free throw line extended. This spreads the floor, opening a huge swath of space all the way to the baseline, exposing the entire backside of the defense to backdoor cuts to the rim.

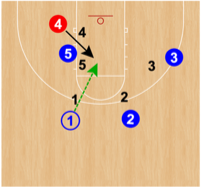

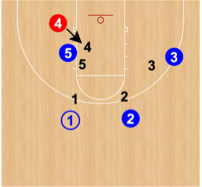

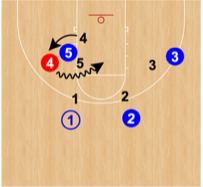

Here’s a quick glimpse of the Tigers’ 2-3 alignment and the flurry of passes, cuts, and exchanges they make in their search for a quality jumper or layup.

The offense is fun to watch and over the years has been widely copied, but… a little secret: if you don’t have two or more proficient jump shooters, the offense is a bust.

This next clip demonstrates the importance of jump shooting in the Princeton attack and ends with a spectacular backdoor in the closing seconds of Princeton’s upset victory over UCLA in the 1996 NCAA tournament.

The Princeton attack is rightfully famous for its emphasis on old fashioned fundamentals and nifty passes to cutters sneaking behind the defense for uncontested layups, but the strategy only works if it threatens the defense with efficient jump shooting. If not, the defense will ignore the perimeter and pack the interior, daring you to drive. No jump shots, no layups.

Ironically, an early season loss to North Carolina during Princeton’s marvelous season of 1997-98 is a good illustration of this principle.

At the time, UNC was ranked #2 in country and would finish the season ranked #1 despite a disappointing loss to Utah in the NCAA tourney semi-finals. But UNC’s coach Bill Guthridge didn’t take the 22nd ranked Tigers lightly. Despite their Ivy League pedigree, he believed they were good enough to compete for the national title. He was especially wary of their disciplined passing and well-timed backdoor cuts to the basket. Film analysis revealed that Princeton was so precise they relied on passing the ball through a 14” wide window on their backdoor cuts. The ball took up 8” of this corridor so his defensive strategy aimed to shave off 3” on either side.

In the end, he succeeded, limiting Princeton to only four backdoor baskets, but barely won the game, 50-42. In fact, Princeton led most of the way, shooting 64% from two-point range but a dismal 15% from beyond the 3-point arc. Convert just three of their 22 missed 3-pointers and they would have erased UNC’s eight-point victory.

Over the season, Princeton’s exquisitely executed backdoor layups were the direct result of their superb jump shooting. They finished 1997-98 ranked 4th in the nation, shooting 50% from the field, making 61% of their two-pointers and 39% of their 3-point attempts. UNC was able to limit the backdoor damage but not the overall proficiency of Princeton’s 2-point shooting. On the season Princeton averaged 14 makes out of 24 two-point attempts; against UNC they were 14 for 22. Only a terrible shooting night from 3-point range in which the Tigers made five fewer 3-pointers than their season average of nine prevented them from springing the upset.

Again, willing and proficient jump shooters create layups, not the other way around.

How Does the Modern 3-pointer Affect the Equation?

To repeat what we noted in Part 1 and again in Part 2, “a jump shot is better than a layup because 3 counts more than 2, but this was true before the advent of the three… it’s the inherent nature of the jump shot that makes the proposition true, not the distance of the shot nor its relative value based on the distance.”

Consider the following statement: “If a team has no dangerous outside shooters, the defense will mass closer to the basket and make it extremely difficult for any offense to get the close-in shots. A driving player who can hit from outside becomes more effective as a driver because he draws the defense closer to him, which makes it easier to get by the defense. A driving game draws the defense back and sets up the good percentage jump shots and a good outside shooting game sets up the drives. Good outside shooters also prevent their defensive men from floating and helping out on defense as much as they would against poor outside shooters.”

Sounds eerily similar to the definition of “gravity” first used by NBA coaches and the analytics community a decade or more ago as the 3-pointer grew in prominence. Yet it was written nearly 60 years ago.

The author? John Wooden in his 1966 classic, Practical Modern Basketball.

You don’t need 3-pointers to create spacing. You need proficient jump shooters. A good shooter with range and proficiency will create space regardless of the value of the shot. The longer his range, the greater space he creates. This is true whether field goals are worth three points or two.

When an offense spreads the floor with capable shooters, it necessarily stretches the defense, creating gaps for driving and penetration. But a poor jump shooting team, no matter its attempts to spread the floor and regardless whether shots are worth 3 or 2, will not pull defenders to the perimeter. Instead, they will sag and choke off paths to the basket.

Because the 3-pointer rewards shooters with an extra point, it’s encouraged several generations of players to attempt an ever-greater proportion of their shots from beyond the arc and their coaches to employ offensive schemes that generate such shots. In the process, players and coaches have rediscovered the central axiom of modern basketball: proficient jump shooting stretches defenses.

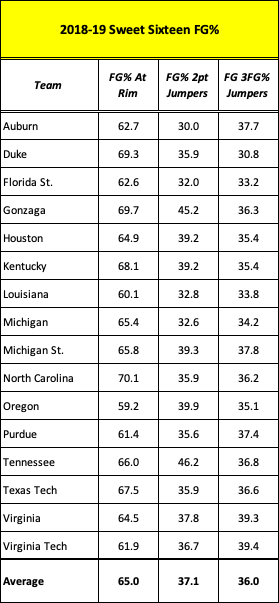

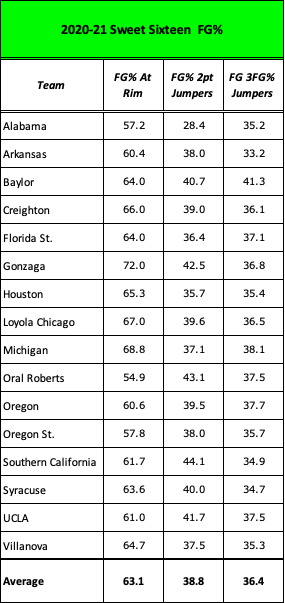

Today, we’ve reached a point where the 3-point proficiency of many teams matches or even exceeds their 2-point proficiency. Here’s look at the NCAA’s two most recent Sweet Sixteen teams comparing their shooting percentages at three distances. (N.B. There was no tourney in 2019-20.)

Thirteen teams – 41% of the two-year Sweet Sixteen field – actually enjoyed better shooting percentages from beyond the arc than inside it. Four of the eight “Final Four” squads shot 3-pointers at a higher clip than 2-pointers, and Houston in the 2020-21 tourney nearly became a fifth.

If we eliminated the 3-pointer tomorrow, would coaches stop spreading the floor? Would they stop guarding a Kyle Guy, Davide Moretti, Corey Kispert, Davion Mitchell, Jared Butler, or Ryan Cline who all shot better than 40% from beyond the arc if such shots were suddenly worth only two points?

I don’t think so.

You have to defend good shooters wherever they are. That may be the 3-pointer’s greatest contribution to basketball.

Controversy

From its start, jump shooting sparked debate.

The establishment – coaches, administrators, and sportswriters – worried that the jump shot threatened the team-oriented purity of the game. For sixty years players had weaved and cut and set screens, passing the ball five or six times until it found its way to the open man, but now a shooter like Kenny Sailors could take a few dribbles, rise up, and shoot a basket, all on his own.

“What’s ruining basketball is the jump shot,” wrote NY sports columnist, Jimmy Breslin, in 1956. “Nearly all your big scorers have it. It’s impossible to stop, and the way the modern player can shoot, you almost wonder how he ever misses… The jump shot today is the bread-and-butter part of basketball. It requires no team effort. Just a guy who can jump and shoot with made-in-the-laboratory accuracy. It has driven the basketball’s main feature almost out of the game. That’s the give-and-go play, the sport’s version of the hit-and-run…. In give-and-go basketball, the play’s object is to work the ball until you’ve got two defensive men in a position where, if an offensive man cuts to the basket, they bang into each other. The result is usually the offensive man taking a pass at full speed and laying it in with the same motion.”

A year later, Harry Grayson, Newspaper Enterprise Association sports editor, joined Breslin: “Basketball today, however, is doing a fine job of killing itself. One word sums it up: repetition. Shoot and score, then throw it up again – that’s all they’re doing except in isolated cases from coast to coast. The jump shot is the big thing. Kids are coming out today with deadly eyes. They get any place near the basket and up they go. . . .The combatant today in college basketball hardly knows basketball at all. All his practice time is put into this shot. By the time he is a varsity starter, he is a tall, quick-moving boy who can shoot. That is fine, but where does it leave the game? The jump shot has stripped all the technique from the sport.”

Coaches, in particular, felt the game was slipping away from them.

They had seen their sport evolve from a stop-start-stop game dictated largely by them to a game of continuity and transition controlled by players. Eliminating the jump ball after each field goal back in 1937 meant they could no longer align their players around the midcourt circle, hoping to seize the tip and begin their attack like a football team snapping the ball to launch a pre-designed play from the line of scrimmage. Luisetti’s running push shot, followed a decade later by Sailors’ vertical jumper forced coaches to surrender even more control.

Seven-time NBA all-star and later coach of the Detroit Pistons and New York Knickerbockers, Dick McGuire, summed up the general consensus in the mid-1950s: “You set up a play, pick off a man clean. You’ve got a man home free underneath. Feed him and he scores. It took four or five good moves to get it done. But you figure it was worth it. You scored. Then the other team brings the ball down. They make one pass. The guy goes up into the air so high you he’s looking for somebody in the mezzanine. Then he shoots and – bingo! – he’s got his basket. Now you have to go back and work for yours. Makes you wonder. I mean, those jump shots – they make the whole thing so easy.”

Whether they liked it or not, the read and react nature of the jump shot was simply too potent an offensive weapon to ignore. They could design set plays and patterns of movement, but the moment of decision was truly in hands of players whose jump shooting ability freed them to maneuver on their own, literally changing the coach’s scripted play “on the fly.”

In the end, coaches conceded the inevitable, replacing two-handed set shooting with one-handed jump shooting. Ironically, though, many continued teaching the game as it had been played in the pre-jump shot era, unconsciously promoting strategies that actually inhibited the true value of the jump shot. For example, throughout the 1950s, 60s, 70s and even beyond, many coaches continued running offenses that had been popularized in the 1930s and 40s… intricate patterns and plays originally designed to free cutters for layups or time to launch two-handed set shots.

Consider the Drake Shuffle, a five-man, continuity offense pioneered by Oklahoma’s Bruce Drake in the late 1940s and later adopted by Joel Eaves at Auburn and Bob Spear at the Air Force Academy in the 1950s.

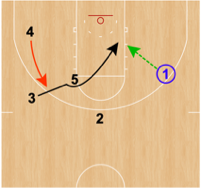

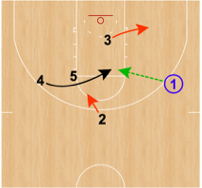

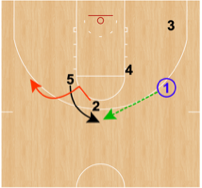

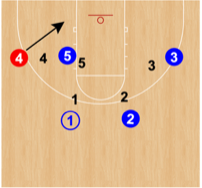

The Shuffle offense is a sequential series of passes and cuts designed to incorporate all five players in a rotating pattern. The progression of steps moves every player through predetermined spots or floor positions and keeps repeating the progression from side to side until the pattern frees a cutter for a layup or a high percentage shot. There are variations and options to the pattern, of course, but the Shuffle’s basic continuity proceeds like this.

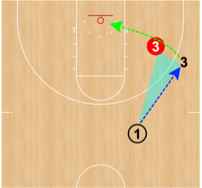

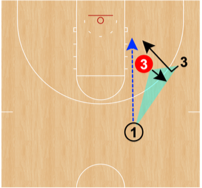

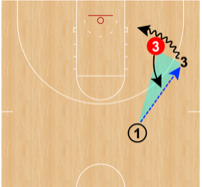

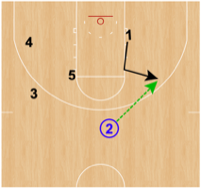

First, the entry pass.

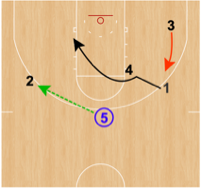

Then, three cuts in quick sequence.

And, the pattern begins again, this time to the opposite side of the floor.

The cutters, of course, are reading their defenders and will often change their routes as the pattern unfolds, or the entry pass might shift to the strong side of the formation, setting up a different set of movements.

The Shuffle celebrates the purity of old-time, traditional basketball, emphasizing patience and ball control. In lieu of one-on-one skills, all players must be highly disciplined, trained in the basic offensive fundamentals of passing, receiving, spacing, screening and rebounding. Most importantly, the offense requires that every player play every position regardless of his size, agility, or skill level. There are no role players; it’s the ultimate team game.

When Bob Spear and his young assistant, Dean Smith, took the coaching reins at the newly opened Air Force Academy in 1956, they were confronted with a team predictably less talented and smaller than its opponents. Their tallest player was only 6’ 4”. To compensate, they searched for an offense that demanded military-like discipline, slowed tempo, controlled the ball, and limited possessions. Smith had played for Phog Allen at Kansas and had experienced defending Bruce Drake’s Shuffle first hand. He thought the offense would be a good fit for the Academy and convinced Spear to adapt and make it his own.

Spear not only employed the Shuffle that first season, he became a committed devotee of the offense, using it for the next fifteen years until his retirement in 1971. By repeatedly moving the ball from side to side and interchanging each player in all five positions, he found that with patience he could eventually break down defenses and get the high percentage shots he needed to compete. Here are some film clips of Spear’s Shuffle during his final season at Air Force.

Beautiful symmetry, elegant in design, and for a traditionalist, poetry in motion… but in the post-jump shot era, it’s impossible to hide the Shuffle’s limitations.

First, it’s mechanical, predictable, and congests the floor, smothering opportunities for read and react, freelance basketball.

When Dean Smith left the Air Force Academy to become head coach at North Carolina, he took the Shuffle with him but eventually abandoned it. Though he had always urged his players to look for opportunities to score within the Shuffle, he found that too often they focused on executing the pattern as it was diagramed, missing the freelance opportunities that naturally presented themselves. “This motivated our search for an alternate offense that would free the player’s mind to concentrate on playing basketball” (emphasis mine). Smith kept the Shuffle in his playbook throughout his career, using it in certain situations, but replaced it as UNC’s primary attack with his freelance “passing game” in the mid-1960s.

Second, the Shuffle treats every player the same.

It’s an equal opportunity offense like the batting order in baseball requiring every player to take his turn at the plate. By forcing everyone to play every position whether they’re suited for a particular position or not, the offense fails to accommodate the strengths and weaknesses of each player. What happens to the exceptionally quick guard who is a superb jump shooter from long range? The proscribed pattern forces him into roles that squander his talent. In the Shuffle he eventually ends up at the high post with his back to basket, screening for other players, then pulling to the point position to become a passer. What happens to a Michael Jordan or Charlie Scott in such an offense? Or big men like Bob McAdoo or James Worthy?

Early Jump Shooting Offenses

The Shuffle is but one of many “old school” offenses that merely subsumed jump shooting into its basic scheme while ignoring the speed, flexibility and lethality the jump shot offered. The set shot disappeared but the complicated cutting patterns and multiple passes these offenses relied upon to create separation remained… even though the jump shot had largely obviated the need for all the complication.

For these traditionalists nothing really changed. They continued coaching basketball as they always had, corralling players within their patterns and scripted plays, seemingly unaware that the jump shot had fundamentally changed the nature of the game.

Meanwhile other coaches embraced the jumper, modifying their attacks to harness its full potential, confident that it would lead to a simpler, freer, and more proficient game.

In Cincinnati, coach Ed Jucker believed a simpler approach to offense was best. “Too many young coaches,” he theorized, “waste too many hours devising “razzle-dazzle” offenses and freak defenses instead of concentrating on the simple elements that lead to success. The fewer passes needed to bring the ball into a good position for a shot, the better. The less dribbling, the better…”

For Jucker, the modern jump shot was the avenue to simplicity.

When he took over the head coaching reins at Cincinnati in 1960, he replaced the Bearcats’ run-and-gun offense with a deliberate half court attack that stressed high percentage shots. He wanted an offense that operated from the center of the cylinder to the foul line, an area circumscribed by an arc of 13 feet, 9 inches.

Jucker found the double screen he so often saw in NBA games very interesting – not the screen or pick itself – but the “scraping action” of the cutter moving without the ball and rubbing his defender off the stationary screeners to gain separation. This gave him an idea he called the “swing and go.” He persuaded his best jump shooter, All-American forward, Ron Bonham, “that 15 well-selected shots could be as persuasive as 25 random ones.”

Starting with a traditional 2-3 alignment, Jucker repositioned Bonham closer to the basket – along the lane, near the block – several feet behind the pivot man, George Wilson.

This forced Bonham’s defender into a difficult defensive situation. Bonham’s first move was always inside and up the lane. To prevent him from catching a pass near the basket, the defender had to play higher, blocking Bonham’s path to middle of the lane.

However, in this position the defender was susceptible to be being rubbed or scrapped off the pivot man if Bonham changed his path, swinging around the pivot. Bonham could now catch the ball unguarded 12 feet from the basket with his dribble still live.

The two defenders were forced to give up a relatively easy, catch and shoot jumper or switch assignments causing a likely mismatch. Even if Bonham’s defender managed to fight over the top, he had little or no cushion left and was vulnerable to a shot fake and drive, and was likely to get screened a second time by Wilson, thus setting up a classic pick and roll.

Jucker’s “Swing & Go” offense was based on the threat of a simple, catch and shoot jumper, and the sequence of read and react options that flowed naturally from it – the shot fake and drive, the pull-up, the two-man pick and roll.

Ironically, after two consecutive national championships in 1961 and ‘62, Jucker ran into Loyola Chicago in the 1963 NCAA Finals, a team that harnessed the jump shot in a different way: the fast break.

Like the rest of the fast break community, Loyola was already wedded to a freelance, open style of play, so the jump shot was easily integrated into their quiver of arrows. They continued to run and press and score in rapid spurts, and when forced into a half court set, spread the defense much like Princeton, using the speed of the jump shot as the fulcrum to generate greater overall pace and score even more points. Dramatically, in their championship game against Cincinnati, Loyola fell behind by 15 points, but in the final 14 minutes of regulation, outscored the Bearcats, 24 to 9, and sent the game into overtime. They ended up winning 60 – 58 as time ran out.

The statistical difference between the two teams was astounding: Cincy shot 48.9% on 45 field goal attempts while Loyola shot a horrific 27.4% from the field. But the Ramblers generated 84 shot attempts. In the second half, Cincinnati slowed the game and stopped shooting, attempting only 17 field goals. Loyola kept firing away, attempting 48. Recall what we said at the outstart: jump shots are easy to generate… a team that takes more jump shots can outscore a team that takes fewer shots even if it makes baskets at a poorer percentage rate.

The following year, UCLA’s John Wooden won the first of his ten national championships using an offense he had conceived in the early 1930s, a full decade before Kenny Sailors thrilled NYC crowds with his theatrics in Madison Square Garden: a 2-1-2 high post attack that was actually strengthened when the jump shot grew in prominence twenty years later.

The early seeds of the offense were planted during his All-American days at Purdue but evolved in 1936 when the NCAA passed the 3-second rule prohibiting teams from camping their big men in the lane for longer than three consecutive seconds. In response, coaches began positioning their centers at the high post, either directly above the free throw line or on the side of the lane in the area we now call the “elbow.” From this position the center became the “pivot” of the offense, receiving the entry pass, then handling the ball as his teammates cut and swirled by him, looking to find the “open man.” Eventually, defenses countered by collapsing on the high post making the entry pass difficult. In response, guards began entering the ball to the forwards to initiate the offense.

In his early days as a high school coach, first at Dayton High School in Kentucky and later at South Bend Central in Indiana, Wooden added one more refinement: as the guard completed his pass to the forward, he cut sharply off the back of the high post to the basket looking for an immediate return pass. This penetrating action triggered the rest of Wooden’s offense and was later crowned the “UCLA cut.”

When the jump shot replaced the set shot, Wooden’s offense grew more potent. It was as if he had anticipated the emergence of the jump shot. He didn’t have to change a thing. The alignment of the offense and its sequence of actions benefitted from the speed and explosiveness of the shot. Here are some illustrative clips of the Wooden offense during the 1970-71 season, first reviewed in Keep It Binary, Stupid where we explored the UCLA attack in greater detail.

By the late 1960s and early 70s the jump shot was fully weaponized. An increasing number of coaches gave their better shooters the green light. Seventeen of the 26 highest single-season scorers in NCAA history played between 1968 – 78. Rick Mount at Purdue, Calvin Murphy at Niagara, LSU’s “Pistol” Pete Maravich and Mississippi’s John Neumann were routinely attempting 30 to 40 shots per game and scoring 35 or more points.

In South Bend, Notre Dame was in the midst of four consecutive winning seasons of twenty or more games, something the school had never done before. Irish coach Johnny Dee loved the fast break and an NBA-style set offense driven by freelance pick and roll and multiple two and three-man set plays. In the 1969-70 season, though, he jettisoned his set offense at the urging of assistant, Gene Sullivan, and implemented a half-court offense based in part on Ed Jucker’s “swing and go” attack. The press dubbed the offense the “double stack” and shooting guard, Austin Carr, took flight, over the next two seasons averaging 38 PPG while shooting a phenomenal 53% from the field.

The “stack” or “iso” as Sullivan liked to call it was an organized system of multiple formations and freelance movement designed specifically to exploit the power of the modern jump shot and free Carr and his teammates to move without the ball. As Carr later recounted, “Scoring in a system is totally different than taking the ball and saying, ‘Give me the ball and get out of the way.’ If I got the ball and wasn’t open for a shot, I had to give it up and then go back through whatever the next side of the play was. So… I would get it back, but first I have to give it up.”

Notre Dame’s success rested squarely on the high-scoring Carr and his teammate, Collis Jones.

Together, during their junior and senior years, they accounted for 58 points or 63% of the team’s 91 PPG average. In NCAA tournament play, the tandem set a two-man, NCAA tournament scoring record that has stood for fifty-two years. Over the course of six tournament games spanning two seasons, they produced 423 points, shooting 50% from the field and averaging 71 points per game. Carr, of course, holds the single-game tournament scoring record of 61 points, along with four other records. In 1971, he was named the Naismith Player of the Year and NBA’s top draft choice.

Like Jucker’s “swing and go,” the Notre Dame stack offense was primarily a jump shooting offense that shortened defensive reaction time, leading to layups and short pull-up jump shots when the defense overplayed its hand. The key difference was pace: ND continued to fast break and in its the half-court set, often generated a field goal attempt with a single pass.

Three hours down the road from Notre Dame, Indiana’s Bobby Knight struck a happy medium, winning the first of his three NCAA titles in 1976, using a jump shot savvy attack similar to UNC’s passing game, he called the “motion offense.” It was faster paced than Jucker’s “swing and go” but more patient than Notre Dame’s “iso” attack.

He deployed his players in different combinations without regard to traditional positions, constantly moving and setting screens for one another, passing until a teammate became open for jump shot or an uncontested lay-up. It was a free-flowing, relatively unrestricted scheme requiring his players to read and react to the defense, guided by a simple set of rules. For example, Knight insisted on proper spacing to spread the defense, ensuring that each player had sufficient room to maneuver as he read the defense. “The width of the floor has to be covered and I want everybody to be 15 to 18 feet away from the next guy,” instructed Knight. To coordinate their movement, he set three basic, but flexible rules:

• Pass and screen away: players pass to one side of the court and seek to screen for players on the opposite side of the court. The hope is to create spacing and driving lanes to the basket.

• Back screen: players in the key seek to screen players on the wing and open them up for basket cuts.

• Flare screen: a player without the ball on the perimeter seeks to set a screen (usually near the elbow area of the lane) for another player without the ball at the top of the key area.

Over the years, many have attributed today’s near obsession with offensive and defensive efficiency, and error-free basketball to Knight. After all, his mantra is frequently quoted: “Victory favors the team making the fewest mistakes.”

But it’s not really true.

To be sure, Knight’s arrival in the Big Ten in 1971, quickly followed by six conference championships and two national championships in his first ten seasons, captured the attention of his fellow coaches. Pretty soon everyone in the league wanted to copy his success formula. The league’s long history of fast breaking, high scoring teams gave way to a greater emphasis on team defense and deliberate, risk-adverse offense.

You’re mistaken, though, if you think Knight’s Indiana teams played like programmed robots.

His first national championship team in 1975-76 averaged 82 points per game. There are few D-1 teams today averaging more. And his renowned “motion offense” depended upon read-and-react decisions by the players, not instructions shouted from the sideline.

Despite the image of the screaming, in-your-face dictator hurling chairs across the floor we so often associate with him, for the most part, Bobby Knight let his players play. He instilled his philosophy and principles in practice and expected his players to apply them during the game.

There’s no better illustration of this than Knight’s 1987 NCAA championship game against Syracuse when, rather than taking a timeout in the final seconds to set up the game-winning play, he trusted his players to get a good shot all on their own. Without any courtside instruction from Knight, they quickly adjusted as Syracuse shifted from its traditional zone into a box-and-one and freelanced the play that sprang Keith Smart for the game-winning shot; a freelanced pull-up jumper from the short corner.

Shoot It or Move it

Increasingly, the coaching community recognized that jump shooting freed players to create separation and maneuver on their own… and much more quickly than the tightly scripted patterns and play calls of the past.

Implicitly, the jump shooting offenses replaced one of basketball’s historic axioms – face the basket in a “triple threat “position for two counts, then act – with a new rule: catch the ball ready to shoot.

In fact, nothing more clearly distinguishes the new approaches to offense from the old school than the fundamental differences between these two axioms.

In the pre-jump shoot era, you caught the ball, faced the basket in a crouched, athletic position, and pondered your options for two counts while surveying the defense. Finally, you acted: shooting, passing, or driving based on how the defense was playing you.

But recall what former player and Princeton coach Joe Scott once said: “We don’t teach the triple-threat position at Princeton… In my entire time as a player, I don’t remember a single time in a game where I caught a pass, came to a stop so I could crouch and place the ball in a triple-threat position.

When you catch the ball, you’ve got to be able to pass or shoot or dribble immediately. If you catch the ball and assume a triple-threat position – crouched and hunched over – you have to come out this stance – you have to stand up – to pass or shoot or attack the basket. And then it’s too late.

The man who passed you the ball and cut to the basket is no longer open; your defender has already closed on you so the shot you would have taken is no longer there; the gap in the defense that you could have driven through has closed.

Instead, it’s your ability to meld three different actions into one seamless action that makes you hard to guard. Players that do these things “separately” are easy to guard. Good basketball players can dribble, pass, and shoot all at once.”

What’s the point of creating separation only to give it back by assuming the classic, crouched-over triple threat position? Any advantage you gained is now lost. The defender is back in your face and your options have been reduced from three to two.

Today’s player becomes triple-threat when he catches the ball ready to shoot. It makes no difference whether the defense is man or zone. It is the immediate threat of the jump shot that triggers the full array of attack options. In the milliseconds during which he brings the ball into a shooting position, the receiver sees the options to drive, pass, or take the shot. This is what Joe Scott means when he says, “Good basketball players can dribble, pass, and shoot all at once.”

To be sure, traditionalists like Knight continued to teach the “triple threat” position throughout their careers – it was ingrained in their devotion to “disciplined, fundamental basketball” and to the game’s coaching legends – but study film of their players in action and you’ll seldom see anyone in shooting range assume the position. They catch the ball ready to shoot and immediately exploit any opening the defense gives them.

Here are some illustrative clips from Bobby Knight’s 1987 semi-final victory over UNLV and his 1984 East Regional semi-final win over Michael Jordan and UNC.

Jump ahead to the 21st century where offenses are largely driven by the analytic value and simplicity of the three-point shot, and you’ll find dramatic confirmation of the new axiom.

Villanova’s Jay Wright, winner of two national championships in recent years has made “catching the ball ready to shoot” one of the hallmarks of his spread offense. “The most open you’re going to be is when you first catch the ball… Catch and think shot. I’d rather have my guys catching like a shooter and maybe some ill-advised threes than having my guys scared to shoot.”

Wright is heavily influenced by Gregg Popovich, head coach of the San Antonio Spurs since 1996 and winner of five NBA championships. “One simple thing,” Wright said. “He has a ‘.5 rule.’ Hold the ball for .5 seconds; if you don’t shoot it, drive it, or pass it in .5 seconds, he’s on you. He wants that ball moving, and he wants people moving. And he really holds the guys accountable to that. I really like that. It’s one of a number of things that we have implemented here in our program.”

Watch the simplicity of Villanova’s offense during their national championship run 2017-18.

Conclusion

Remember the old Woody Hayes football adage? “Only three things can happen when you pass and two of them are bad.”

In basketball the reverse is true. Replace the word “pass” with “jump shot” and you’ll find that once a shot is attempted, seven things can happen and five of them are good for the offense.

• make the basket

• make the basket and get fouled… shoot free throws

• miss the basket but get fouled… shoot free throws

• miss the basket but snag the offensive rebound for a second attempt or tip-in

• get blocked but recover the ball for another attempt

• get blocked or charge in the act of shooting and lose possession

• miss and lose possession

More shots are generally better than fewer shots as the probable outcome is in your favor. Effective offenses produce a greater number of quality shots than their opponents through fewer passes, faster tempo, and the speed of the modern jump shot.

“God is not on the side of the big battalions,” Voltaire once said, “but of the best shots.”