“We don’t teach the triple-threat position at Princeton.”

I nearly fell to the floor.

Here was Joe Scott, former player and disciple of Princeton’s legendary Pete Carril, now the newly named head coach the Tigers, preaching heresy at a coaching clinic.

Princeton, the home of Bill Bradley, the epicenter of traditional give’n go, pass-and-cut basketball, the Mecca of low-possession, conservative offense and the last place on the face of the earth you’d expect to find a coach rejecting one of basketball’s sacred maxims.

“In my entire time as a player I don’t remember a single time in a game where I caught a pass, came to a stop so I could crouch and place the ball in a triple-threat position.

Think about it.

Implicit in the command, “assume a triple-threat position” is the understanding that you have received a pass within shooting range of the basket. If you’re outside your effective shooting range when you receive the ball, your options are already limited to dribbling or passing. You aren’t a credible shot threat so there is no “triple threat” regardless of the stance you take. It is what it is.

But if you’ve received the ball within shooting range we can assume that you worked hard to get free, creating “separation” through your own guile, quickness and hard work, or through the efforts of your screening teammates. What is the point of creating separation only to give it back again by assuming the classic, crouched-over triple threat position routinely advocated by the coaching community for the last seventy-five years?

In their basketball classic, Basketball According to Knight and Newell, Bobby Knight and Pete Newell, two of the greatest coaches of all-time, insist: “We want any player receiving the ball at any position on the court to immediately face the basket for a two-count.”

Let me get this straight. Catch the ball, face the basket, and wait two seconds before acting? Are you kidding me? In two seconds any advantage you gained is now lost. The defender is back in your face and your options have been reduced from three to two.

Joe Scott explains further.

“When you catch the ball you’ve got to be able to pass or shoot or dribble immediately. If you catch the ball and assume a triple-threat position – crouched and hunched over – you have to come out this stance – you have to stand up – to pass or shoot or attack the basket. And then it’s too late. The man who passed you the ball and cut to the basket is no longer open; your defender has already closed on you so the shot you would have taken is no longer there; the gap in the defense that you could have driven through has closed. Instead, it’s your ability to meld three different actions into one seamless action that makes you hard to guard. Players that do these things “separately” are easy to guard. Good basketball players can dribble, pass, and shoot all at once.”

So why do coaches – even brilliant ones — continue to preach the virtues of the triple-threat position?

Dedicated coaches want to “teach” and to do so they take what is naturally seamless and whole, and break it into parts or pieces that they can describe, drill, and measure. Here’s a fairly typical description of the triple-threat position you can find in virtually any basketball instructional book:

1. To be in the triple threat position, you must still have your dribble. The best way is to receive a pass from a teammate.

2. After you have received the pass, bring the ball down to your hip and face your defender.

3. Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, knees bent, and in a slight crouch.

4. Grasp the ball with your weak hand on the side of the ball and your strong hand on top.

5. Bend both elbows so they are approximately at right angles.

6. Once you are in this position you can either pass the ball to a teammate, dribble around the defender, or shoot the ball. Your decision will be influenced by how the defender is playing you.

This wonderfully exacting description, frozen in words, has little to do with how the game is actually played. It’s useful if you’re teaching the game to a gawky 7th grader who must master balance and basic footwork before he can play the game competitively. Over time, though, this form of instruction, mindlessly repeated by successive generations of coaches at all levels, degenerates into “conventional wisdom” that upon serious reflection is utter nonsense.

Listen again to Joe Scott: “In my entire time as a player I don’t remember a single time in a game where I caught a pass, came to a stop so I could crouch and place the ball in a triple-threat position.”

So how does a basketball player achieve “triple threat” without assuming the classic “triple-threat position? Interestingly, coaches Knight and Newell provide the answer when they discuss how best to attack zone defenses:

“We want our players receiving the ball from a reverse pass to go immediately into the shot motion. If the shot is there without excessive pressure, we want it taken. However, if the defensive man is rushing at the shooter, we want to momentarily straighten him with a good shot fake that involves the ball, the head, and the shoulders, and then get past him with a dribble penetration that will force the defense into a different kind of coverage enabling us to free someone else in the zone.”

In other words, you become triple-threat when you catch the ball “ready to shoot.” It makes no difference whether the defense is man or zone. It is the immediate threat of the jump shot that triggers the full array of attack options. In the milliseconds during which he brings the ball into a shooting position, the receiver sees the options to drive, pass, or take the shot. This is what Joe Scott means when he says, “Good basketball players can dribble, pass, and shoot all at once.”

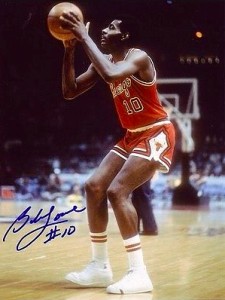

Here are two photographs. The first is a staged photo of Los Angeles Clipper Blake Griffin in classic triple-threat position. The second features three-time NBA all star Bob Love in an actual game catching the ball “ready to shoot.” Which position creates more problems for the defense?