Remember those early scenes in Hoosiers when Coach Norman Dale drills his Hickory High team in his offensive philosophy?

“How many passes?” he implores.

“Four!”

And several scenes later, “How many times are we gonna pass off? How many?”

“Four!”

And then just before their first game, “Guys, remember what we worked on in practice. I wanna see it on the court! How many times are we gonna pass before we shoot? How many?

“Four!”

And then early in the game, Rade, the team’s self-centered hothead, challenges Dale, jacking up several long jumpers without once passing the ball. Dale immediately benches him and even after losing another player to fouls, refuses to reinsert him, content to finish the game with only four players on the floor.

It’s the film’s defining moment because it reveals Coach Dale’s character – his insistence on team work and discipline and selflessness, his belief that there’s a “right way” to play the game that is more important than the outcome. At that point we’re not sure why, but for Norman Dale, this is his last chance, the end of the line. He’s willing to lose the game, infuriate his team and its fans, and risk his job, all for principle. If he retreats now, he knows he will lose everything.

Twenty-nine years since its debut I’m not surprised by the film’s enduring fascination. It’s got everything – the David versus Goliath story line, the celebration of small town virtues, the quiet insistence on integrity, second chances, and the possibility of redemption no matter the depth of personal failing.

But I’m forever amused by how much importance Hoosiers’ fans continue to place on coach Dale’s dictum: four passes.

They leave the film believing that the number of passes that precede a shot distinguishes the well coached team from the poorly coached one; that whether it’s four or six or some other magical number, effective offense requires multiple passes. This notion is reinforced endlessly by t.v. announcers, often former coaches-turned-commentators, who constantly stress the importance of making the “extra pass.”

I was reminded of this several weeks ago while watching the Virginia and Louisville game. ESPN’s Dick Vitale was especially enamored by Virginia, a team that features exquisite offensive patience and efficiency, complimented by a smothering defense that sucks the life out of the shot clock, leaving its opponents with few uncontested shots. To emphasize his respect for Virginia’s offensive prowess, during one particular possession Vitale enthusiastically ticked off the number of passes, one by one. “That’s one touch, two touches, three touches…” When he reached six, a Virginia player took a rushed, unbalanced 14-footer that happened to go in and Dickie V responded with characteristic exuberance. “Oh, baby, what great basketball.” Or something to that effect.

Let me see if I’ve got this right.

Six touches followed by a poor shot that happens to go in is great basketball. So, one touch followed by the exact same shot with the same result must be… poor basketball? Does that mean that six touches followed by a miss is better than one touch followed by a make? Is an offense featuring multiple passes before a shot attempt inherently more effective than one that features fewer passes?

I don’t think so.

A quality shot is a quality shot regardless of how many passes lead to it. Conversely, a bad shot is a bad shot. In fact, one might reasonably argue that offensive maneuvers that generate quality shots quickly and more simply – with fewer passes – are preferred because there’s less chance of turnover.

Think about it. By definition an “extra” pass is just that – extra, unnecessary, not needed. A few examples are in order.

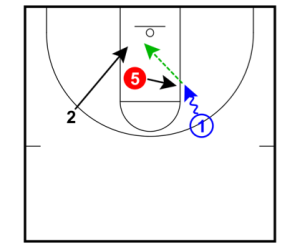

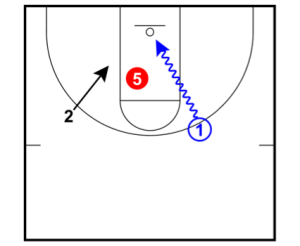

Take the proverbial 2-on-1 break. Most of the time, the most effective maneuver is a straightforward dribble drive to the rim without a pass or, if contested, a single pass resulting in an immediate lay-up or a dunk. Anything more complicated is fraught with risk. In the illustration below, the two offensive players split the lone defender.

The ball handler drives the rim at a 45-degree angle, fully committed to “going all the way.” His commitment to the rim forces the defender to make a decision. If the defender is the least bit tentative, the dribbler continues all the way to the rim. If, instead, the defender commits to him, then and only then does the dribbler pass the ball to his attacking teammate. Occasionally you’ll see the two attackers pass the ball back and forth between them as they proceed up the floor, but each pass presents a risk of turnover.

Let’s examine a more complicated situation: a half-court set. In the twelve-season period between 1963 and 1975, John Wooden’s UCLA squads won ten national championships. The bread-and-butter of their offensive scheme involved a maneuver that became so closely associated with Wooden that it is commonly called the “UCLA cut.” It involves no more than three passes and any one of the passes in the sequence can result in a shot attempt.

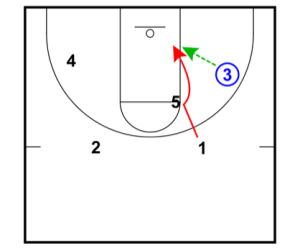

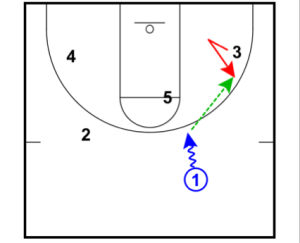

The maneuver begins with a simple entry pass from the guard to the forward. Note that the forward’s cut to the basket followed by his reverse to the wing, can result in an immediate jumper or backdoor cut if the defender is not ready.

The entry sets up the famous “UCLA cut” — a simple give and go move with one important addition. The diving guard attempts to rub or scrape off his defender using the center stationed at the high post. The guard can cut either side of the center in an effort to create adequate space to receive a pass from the forward. If this fails, the center steps out to receive a pass from the forward. In effect, he replaces the diving guard, setting up the next sequence of action.

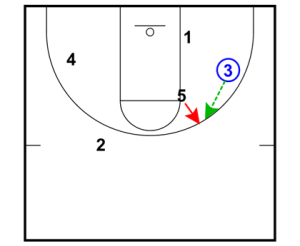

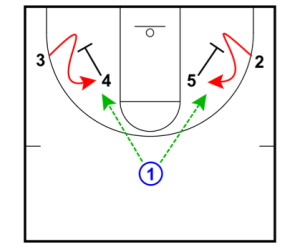

With the ball now in his hands, the center looks for two cutters. The first is the offside forward who breaks sharply to the basket then flashes into the lane.  The second option features a down screen on the ball side, freeing the guard who had originally executed the UCLA cut and is now positioned at the block. Both passes are intended to result in an immediate jumper or drive to the rim.

The second option features a down screen on the ball side, freeing the guard who had originally executed the UCLA cut and is now positioned at the block. Both passes are intended to result in an immediate jumper or drive to the rim.

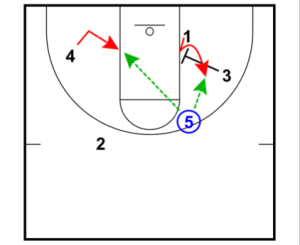

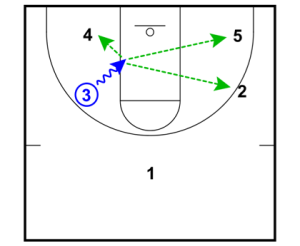

Lastly, let’s return to Virginia’s attack called the “blocker-mover motion offense.” It features a variety of schemes utilizing three perimeter players supported by two interior players who “block” or set screens for their constantly moving teammates. The favorite seems to be a series of cuts and passes that culminate in the following – a wide curl with the receiver catching the ball facing the basket. He can shoot, drive the basket, pull-up if his drive is denied, or if defensive help arrives, make a quick pass to an offside teammate.

Interestingly, while coach Tony Bennett prefers to run time, forcing the defense to guard multiple actions on each possession, the resulting base maneuver can be accomplished with one pass, perhaps followed by a second. It doesn’t require multiple passes to create the same shot.

So, what can we conclude?

First, get beyond Coach Dale’s actual words to the sentiment or principle he’s trying to instill. His insistence on “four passes” is simply a contrivance to foster teamwork and unselfishness early in the season, a way of insisting that his players help one another get a quality shot instead of jacking up the first shot that comes along.

Second, replace the admonition “make the extra pass” with “make the right pass.” An effective offense is one that produces quality shots and creates opportunities for second shots. Spacing, movement, and passing are part of this, but they’re not ends in themselves. A long possession featuring intricate movement and passing that results in a turnover or poor shot is as wasteful as a short possession that results in the same. Coaches who prefer slow tempo with more passing and ball handling are not necessarily better coaches than those who prefer fast tempo with fewer passing and ball handling.

Third, the next time you watch college basketball on television, turn off the sound. You’ll see the game more clearly.

You need as many passes as it takes to get a good shot. The shot can be a 2 footer…10 footer or 20 footer. Get a good open look. Personally I Love the movie Hoosiers. If you remember the game winning shot came after joust one pass.

AMDG

One pass, one shot!

Coach: I am not a great student of basketball but I do understand the concept of getting a quality look and a quality shot. Moving without the ball and getting open is just as important and making that pass. Loved your diagrams…I actually understand some of them!

GO IRISH!

Stump