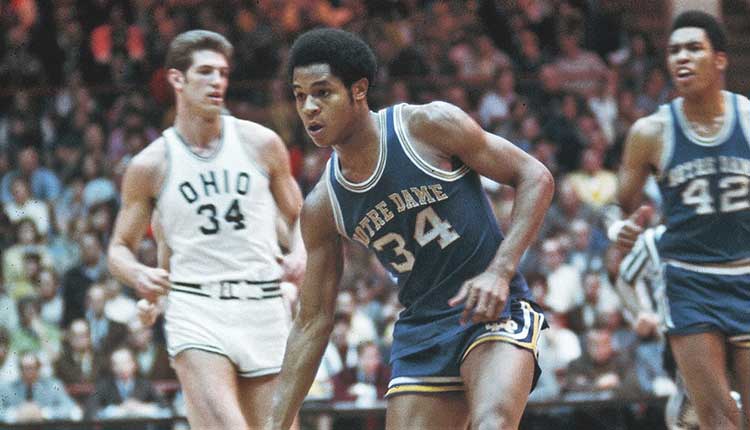

Though the 82nd NCAA Tournament has been scrubbed, we can still celebrate the 50th anniversary of Austin Carr’s single-game scoring record: 61 points in the 1969-70 first round game against Ohio University, the Mid-American Conference champion.

Shooting 57% from the field, the 6’3” Notre Dame guard made 25 field goals out of 44 attempts. He nearly duplicated this amazing feat a week later against SEC champion Kentucky and Big Ten champ Iowa scoring 52 and 45 points respectively. His three-game shooting percentage was 58%.

Significantly, he was joined by teammate Collis Jones who averaged 23 points per game in the three contests. Together, they produced 228 points in three successive tournament games — an average of 76 points per game on 54% marksmanship.

For a detailed look at their amazing feat I invite you to visit the piece I posted last week at Hudl.com. You’ll find a highlight film of their two-man, single-game scoring record (85 points) as well as an intriguing comparison with last year’s tournament field.

If you’re interested in seeing the entire game, visit my YouTube channel. Digitized from an ancient Sony reel-to-reel video tape, the game is not only great fun to watch, but is of historic interest as it marks the beginning of the end of one era in college basketball and the launching of the one we now experience. In many ways, it foreshadows how the college game evolved as it grew in popularity, driven by 24/7 cable coverage and the explosion of March Madness.

In the meantime, here are several Krossover charts I constructed to bring analytic definition to the Carr-Jones record, all of it occurring in an era before the 3-point shot.

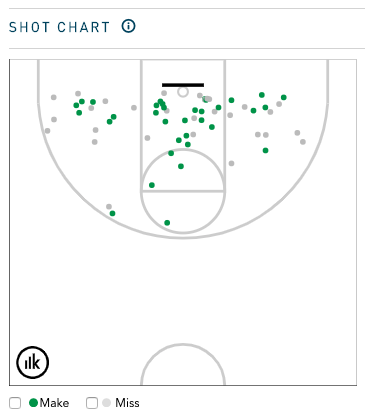

Chart #1: Traditional Shot Chart: 63 FGA, 34 FG, 54%

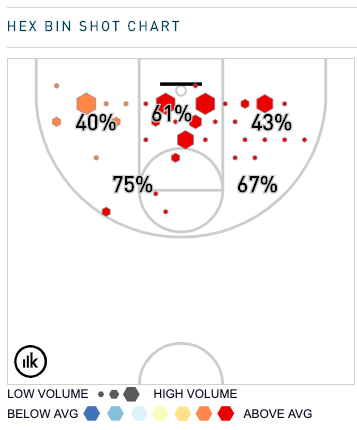

Chart #2: Hot Zone: The Hex Bin Shot Chart shows volume by hexagon size and efficiency by color.

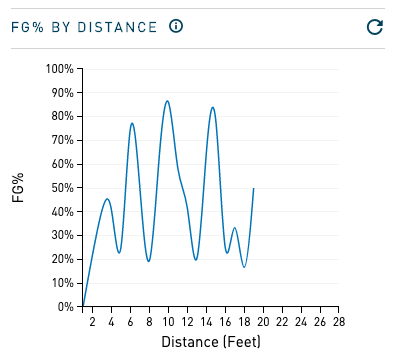

Chart #3: FG% by Distance

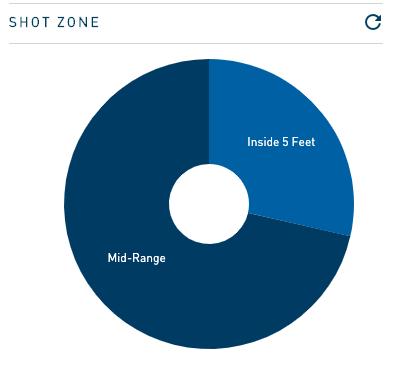

Chart #4: Shot Zone: Midrange: 40 FGA, 20 FG, 50%; Inside 5 Feet: 23 FGA, 14 FG, 61%

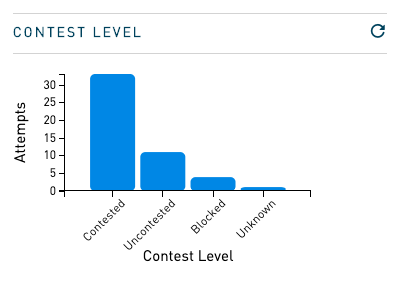

Chart #5: Defensive Contesting Level: Contested: 40 FGA, 22 FG, 55%; Uncontested: 17 FGA, 10 FG, 59%; Blocked: 6 FGA, 0 FG, 0%; Unknown: 2 FGA, 2 FG, 100%

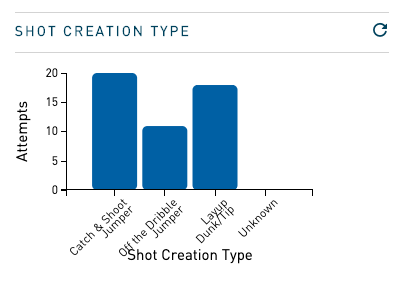

Chart #6: Shot Creation Type: Catch & Shoot Jumpers: 23 FGA, 9 FG, 39%; Off the Dribble Jumpers: 12 FGA,8 FG, 67%; Layup, Dunk, Tip: 27 FGA, 16 FG, 59%; Unknown: 1 FGA, 1 FG, 100%

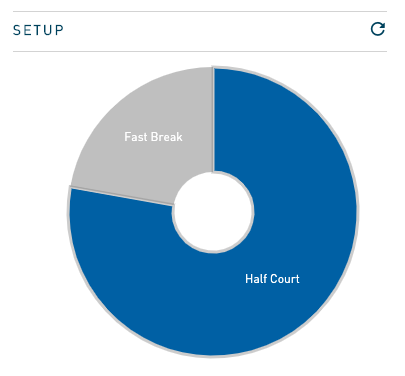

Chart #7: Offensive Set Up: Half Ct Offense: 42 FGA, 24 FG, 49%; Fast Break: 14 FGA, 10 FG, 71%