In the run-up to this season’s Final Four we were greeted by two interesting but unsurprising commentaries. Unsurprising because they merely confirmed what we already knew: that the number of 3-point attempts in college basketball continues to surge, and correspondingly, the number of dunks has followed suit.

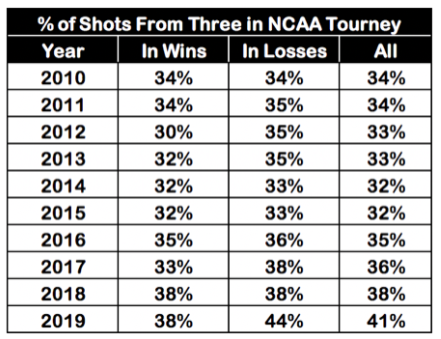

In his April 8th Sports Illustrated piece, citing data compiled by Ken Pomeroy, Andy Staples recounted the record number of treys attempted in the tournament. Back in 2014 and ‘15 the percent of three-point field goal attempts per tournament game hovered around 32% but rose to 35% in 2016, then cleared 38% last season. Through the first 64 games of this year’s tournament, Pomeroy found that the average percent of three-point attempts had grown to nearly 41%.

Hoop Vision’s Jordan Sperber chimed in with a nifty chart, illustrating the trend over a ten-year period.

And what does the dramatic uptick in three-point attempts have to do with the increasing number of dunks generated in this year’s tourney?

Josh Plano’s March 28, 2019 piece at FiveThirtyEight.com revealed that six of this year’s Sweet 16 entries had a dunk share, or percent of 2-point attempts, exceeding 10%. Four years ago, only one did. “This is less about a few dunk-crazed teams and more a reflection of the nationwide trend in college basketball,” reported Plano. On the eve of the Final Four, the season had produced 19,550 dunks, about 2,000 more than just five years ago.

And the reasons?

“We’re seeing more dunks,” ESPN analyst Jay Bilas told The New York Times, “because there are more spectacular athletes out there.” More significantly, though, Bilas cited the symbiotic relationship between 3-pointers and dunks.

The rise of the three as a strategic weapon has created an either-or game: you shoot the three or drive to the rim for a high percentage layup or dunk. You avoid all other lower percentage 2-point attempts. Throw in the long-range accuracy of a Carson Edwards or Kyle Guy and the crazy athleticism of players like Zion Williamson and Ja Morant, and you end up with lots of threes and dunks.

Again, interesting but not really surprising.

While the three-pointer has greatly influenced offensive schemes and strategy, I sometimes wonder if the media echo chamber has overly dramatized its importance, imbuing it with near magical qualities when its actual benefits are, in many ways, quite relative.

Continue reading…