When I finally tuned in there were less than ten minutes to play.

9:35 to be exact.

Kentucky’s Johnny Juzang had just knocked in a 3-pointer to increase the Wildcat’s meager lead to eight, 58-50. Twenty-four seconds later, Texas Tech missed a jumper, foreshadowing the utterly dreadful nine minutes of basketball that were about to unfold.

Eventually, Kentucky pulled out a 76-74 victory in overtime but I never got that far. The final minutes of regulation play were enough for me. In all, 4 field goals, 10 turnovers, 10 fouls.

On average, over the course of nearly ten minutes of play, two top-20 teams, representing premier D-1 programs with access to the best recruits in the country, collectively generated one basket every two minutes and forty seconds of play. Yikes!

Ten seconds after a timeout at the 1:11 mark, the Wildcat’s Tyrese Maxey missed a quick jumper and was promptly criticized by ESPN’s Jimmy Dykes. “Not a good shot… you gotta run some offense.”

“Jimmy,” I shouted at the screen, “I’ve watched Kentucky ‘run offense’ for the last nine minutes and nothing good has happened.”

When your offense produces one basket on seven shot attempts during the final quarter of play – that’s roughly a field goal attempt every 1 minute and 43 seconds – there’s not much benefit to “running some offense.” You might as well jack it up and hope that by increasing your attempts something eventually goes in.

For their part, Texas Tech didn’t fare much better. During those final 9:35 they went 3 for 12 from the field, only catching Kentucky as regulation expired on the back of seven free throws.

Look, I get it.

Every team has an off night or stretches in a game when the wheels come off. And lots of time, the bad play becomes infectious, one team dragging its opponent into the mire. Last Saturday’s game between 15th ranked Kentucky and 18th ranked Texas Tech is neither indicative of their true prowess or representative of the state of college basketball this season… but it’s not far off, either.

We began this season with coaches, commentators, and fans all asking the same question: how will college basketball’s new 3-point line affect the game?

Will extending the line to the international distance of 22 feet, 1¾ inches curb the game’s growing emphasis on the 3-pointer, leading to greater variety in offensive style and strategy as the NCAA intends? Will shooting percentages at the longer distance remain sufficient to pull defenders even farther from the basket, opening the floor for more dribble drives and offensive maneuvers inside the arc? Will players who lack long-range proficiency rediscover the value of the post up and short range jumpers?

With two-thirds of the season behind us we can reach some tentative conclusions.

First, players are still in the midst of adjusting to the new distance. Since early November the basic indices have consistently trended downward. Points per game have fallen to 71.6, two points lower than where they stood just two seasons ago. In the same time period, overall field goal and 3-point shooting percentages have both slipped with 3-point accuracy nearing its historic low of 33.9%. According to Ken Pomeroy “efficiency” or points scored per 100 possessions is at a 17-year low. “As with every season” he cites, “shooting will improve and players will commit fewer turnovers. But it’s almost certain that offensive efficiency will continue to lag a few points behind what we’ve seen over the past four seasons.”

Nevertheless, the negatives we’ve seen this season are slight and will surely rebound with time and natural adjustment as they have every time the 3-point line has been extended.

For example, like the NBA, the new and deeper college arc runs out of floor space as it curves its way to the baseline. Consequently, at a certain point, the arc is forced into a straight line running parallel to the sideline. This creates an advantage for 3-point shooters as the distance from the corner to the center of the cylinder is 6” shorter than everywhere else along the arc.

But it also creates a problem.

In the corners the corridor between the 3-point line and the sideline is uncomfortably narrow, only 35.4 inches wide. This season many players have found it difficult to stay in bounds when launching the corner three. Either they step onto or across the 3-point line, unintentionally creating a long range two-pointer, or they step too far back and end up out of bounds. In response, coaches are teaching new footwork tactics. Most right-handed shooters catch with the left foot forward and step into the shot with the right foot, so Iowa State coach Steve Prohm is teaching his players to catch on two feet and go straight. Texas Tech’s Chris Beard is taking a different approach, teaching his players to side-step. Whatever the change in tactics, players will soon adapt and take advantage of the corner three like their NBA counterparts. When that happens, shooting percentages and points scored will rise.

Second, though offensive efficiency will recover, it will likely settle at a level reflecting the overall decline in scoring that began nearly fifty years ago. The 3-pointer, shot clock and freedom of movement rules implemented and revised on six different occasions remain insufficient to reverse the overall decline.

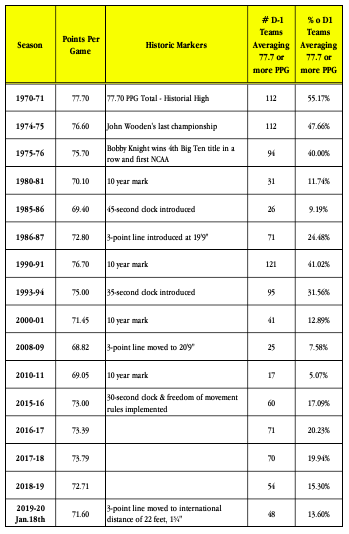

Note the following chart. Scoring reached its apex in 1970-71 when D-1 teams averaged 77.7 points per game. Two seasons later, in 1974-75, scoring began its long downward slide.

By 1985-86, when the shot clock was introduced, scoring had declined by eight points. More dramatically, the percentage of D-1 teams continuing to match the average high of 77.7 or higher had collapsed from 55% to 9%. The trend only began to reverse when the three-pointer was introduced, rewarding an extra point for longer range field goals.

However, by 2010-11, forty years after the high water mark, scoring again dipped to 69 points per game and the percent of teams holding at or above the high water mark of 77.7 shrunk to 5%. Keep in mind, this decline occurred in the midst of the 3-point revolution. If you convert 3-point field goals to replicate their 1970-71 value – two points instead of three – you end up with a disappointing per game average of 62.8 points. That’s 15 points lower than the high in 1970-71.

Now, jump to the current season. The numbers are slightly higher than 2010-11 but slightly lower than last season. Against the overall 49-year trend line, the differences are insignificant.

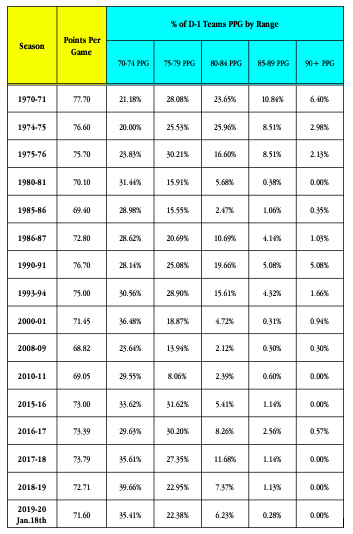

Let’s add some more definition to our examination of long-term offensive trajectory… the same milestone seasons but a review of average points per game by various ranges.

In 1970-71 nearly 41% of D-1 teams averaged 80 points or more; forty years later, in 2010-11, with the 3-pointer and shot clock firmly ensconced in offensive strategy, only 3% averaged 80 points or better. Last season, 9%; this season 6%.

Again, the overall trend lines are firmly in place. Once players adjust to the new line, offensive indices will rebound slightly and the college game will settle at a level representative of the 3-point era.

Third, and most important, extending the 3-point line by a mere 16 ¾” is not great enough to reduce the emphasis on the three-pointer and bring variety to offensive strategy as the NCAA intended.

To curb or retard 3-point dominance means shrinking the percent of field goal attempts taken from beyond the arc. There are only two ways to do this. Either increase the pace of play to a point where the overall number of field goal attempts grows while the number of 3-pointers falls as a percent of the higher total, or hold the current overall field goal attempts constant while the number of 3-point attempts falls. There’s no evidence that either event has occurred or ever will occur.

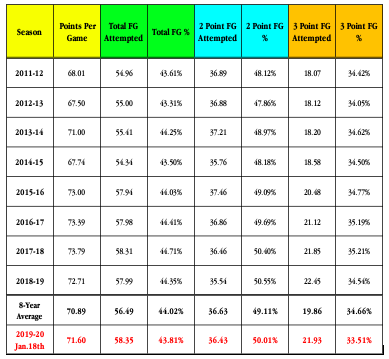

Consider the following the chart.

This illustration traces the history of field goal attempts and shooting percentages over the last eight seasons, then compares those results against the current season. Note that since 2011-12, the average number of field goal attempts has remained fairly constant, ranging between 54 and 58 attempts per game, an average of 56.

But this season’s average is 58 and the number of 3-point field goal attempts is 22, two more attempts the eight-year average. Despite the deeper arc, teams are taking more 3-point jumpers this season, not fewer.

Hidden in those figures is a much more telling sign: the number of 3-pointers as a percent of all field goal attempts has actually grown. In the eight years between 2011-12 and last season, the average number of 3-point attempts constituted 35% of all attempts. As of January 18th this season, the figure is 38%.

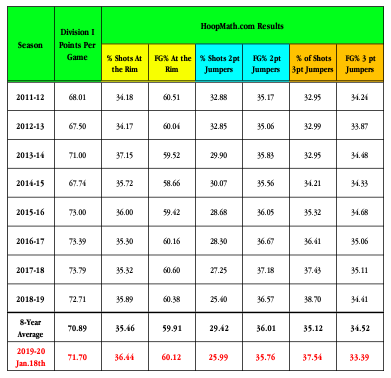

So far, the deeper arc has not curbed the emphasis teams place on the 3-pointer, nor has the increased space inside the arc fostered greater diversity in offensive style and strategy. Here’s another chart constructed by pulling data from Jeff Haley’s HoopMath.com.

Look at the percent of field goal attempts inside the arc – “at the rim” attempts (layups, dunks, tip-ins) and two-point jumpers. This season compared to the average of the previous eight seasons reveals that the percent of shots taken “at the rim” has increased slightly, from 35% to 36%, perhaps indicative of the deeper arc generating more dribble drives as the NCAA intended, but not significantly higher. More importantly, the percent of two-point jumpers is nearly 3½% lower than the eight-year average.

Despite NCAA’s best intentions, the new 3-point line hasn’t changed offensive strategy and tactics in any appreciable way. The offensive sets and styles we’ve seen over the last decade or more remain essentially the same. Team A shoots and misses, forsakes the offensive rebound, and immediately falls back to prevent a run out. Team B snags the rebound, attempts a run out, and when denied, runs a ball screen to set up the dribble drive. More often than not, this results in one player dribbling, one screening, and three standing around hoping to receive a pitch out for an uncontested three. Everyone does the same thing.

These outcomes were predictable. Like most bureaucracies, the NCAA legislates change incrementally. Over the last thirty-four years the association has adjusted 3-point line on two occasions, each time lengthening the arc to make the shot more challenging and to expand the space inside the arc to encourage freedom of movement and offensive variety. But they never go far enough. As West Virginia coach Bob Huggins, a member of the NCAA rules committee, said last summer, “We didn’t move it back enough to make a difference. All this stuff about there’s more spacing and it’ll be cleaner and all that, that’s bullshit.”

The line needs to move to the NBA distance of 23 feet, 9 inches. This will dramatically shrink the pool of college players whose shooting proficiency makes them credible threats from the longer distance and force coaches to devise more varied strategies than the current “either/or” game in which a dribbler attacks the rim in hopes of a layup or dunk, and if denied, pitches the ball to a teammate for a 3-point attempt.

Relocating today’s line at the international distance increased the operating space inside the arc by roughly 100 square feet. Moving the arc back another 19 ¾” to NBA distance will expand this space even more. Add the fact that the college lane is still set at 12 feet, and you end up with more space between the elbow and the 3-point line than any other basketball court in the world. There’s a lot more you can do in that space than simply dribble drive the basket. Coaches will define new roles (or rediscover old ones) for the remaining players on their rosters to exploit, roles requiring skills for life “inside the arc.” Offenses will become more varied and less predictable.

If you fear that such a change will, instead, replicate the NBA’s style of offense and destroy the college game’s distinct flavor, consider the following: in any given year, about 550,000 young men play high school basketball; in round numbers, 4,550 of them are offered D-1 scholarships (13 scholarships per team, 350 teams). How many of these players will emerge as reasonable threats attempting 3-pointers from the NBA line during their college days?

Right now, there are 154 NBA players who average three or more 3-point attempts per game and make 35% or more of them… 154 of the finest players in the world. For the sake of argument, let’s presume that there are 154 D-1 players who could perform equally well. In fairness, add another 146 D-1 players to the mix who lack the overall skill to play professional ball but whose long range shooting prowess could benefit their college teams. That’s 300 players we’d trust to take NBA distance jump shots. What are we going to do with the remaining 4,250 players on scholarship? Who’s going to guard these kids if they’re standing outside the arc?

“I wouldn’t be opposed to them moving it back to the NBA line,” Pomeroy said earlier this season. “I think the more you move the 3-point line back, the more it becomes a true skill, and so the good shooters can take advantage of it and the bad shooters can’t.”

Take the “bad shooters” off the line and offensive strategy will change dramatically because you have to find spots on the floor to place them – spots and roles that utilize their strengths and minimize their weaknesses. We’ll see less reliance on the 3-pointer and greater offensive diversity.

Until then, it’s more of the same.

thanks Mark—always interesting—the 3 point rule has changed basketball at all levels and deserves analysis. I watched part of the second half of the Celtics-76ers game last week and while I watched, the 76ers shot approx 15 three pointers vs 1 two point shot—-they missed every 3 pointer and the game was over. Very boring. But the 3 pointer has provided us with better athletes. Rick Mahorn wouldn’t play today. The goons are gone. The court has opened up

and you get better athletes because they have more room to move. Hockey eliminated the two line off sides rule and that opened up the rink and the game became less physical and highlighted the skilled players. And similar to basketball, the change brought in European players. I think it works better in hockey. In basketball, the 3 point line is a mixed blessing.

You’re on target as always, Chris. I love the open floor and the room it gives “athletes” to maneuver. My problem with the prevalence of the 3-pointer in college is that it has created an “either / or” game of layups or 3-pointers with very little in between and a tremendous amount of time is expended as teams search for one or the other. They talk a lot about “space and pace” but the pace is actually significantly slower today. True, most teams today run the ball down the floor in transition (very few walk the ball up the court) but when denied — and most are — they spend lots of time before a shot attempt is taken. Overall field goal attempts have been down for years in the name of analytic “efficiency.” Consequently, teams today average about the same number of field goals as they did in the early 1950s. Thanks again for reading my stuff and taking the time to comment.