It’s over… finally. Much of it unwatchable. The slowest, lowest scoring collegiate season since 1981-82. In fact, you’d have to go back 64 years to 1951-52 to find a less productive season. That’s an era when many players still relied on two and one-handed set shots.

The tournament, of course, presented many of the old delights – the “combination of upsets, buzzer-beaters, frenzied comebacks, court-storming, dancing, and weeping” recently noted by ESPN’s Brian Phillips – but also contributed to the season-long agony of pushing and shoving, interminable timeouts, coaches prowling the sideline, often straying onto the court, jump shots clanging off the rim… well, you get the picture.

- According to analytics expert Ken Pomeroy, three of this year’s Final Four teams ranked outside of the top 200 in tempo. The lone exception? Duke ranked No. 114.

- In its semi-final game against Duke, Michigan State scored 14 points in the first 3:42 of play followed by only 9 points in the remaining 16:18 of the half. Duke advanced to the finals on the back of 27 free throws and 26 field goals in 40 minutes of competition. That’s an average of one basket every 90 seconds.

- Forty-eight hours later, the halftime score of Duke’s national championship game with Wisconsin ended 31 apiece. In the 1988 matchup, Kansas and Oklahoma battled to a 50 – 50 tie in the same period of time, collectively outscoring this year’s stalwarts, including nine McDonald’s All Americans, three of whom are surefire one-and-doners, by 38 points.

- The final five minutes of the Duke – Wisconsin brawl took 18:41 minutes of real time to play.

To place the dismal offensive performance of this year’s tournament in historical perspective, consider the following:

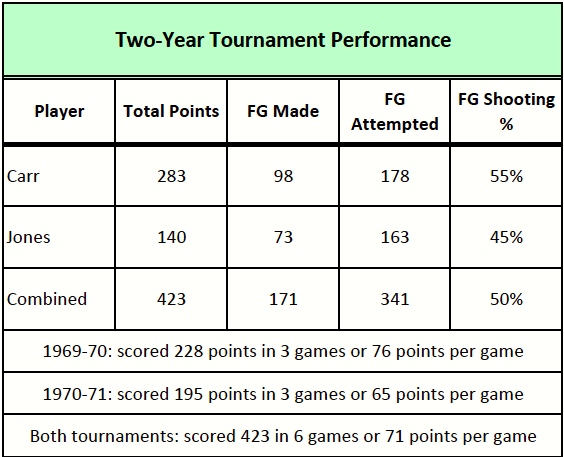

Forty-five years ago, during the 1969-70 tournament, Austin Carr set the March Madness single-game scoring record of 61 points against the Mid-American Conference champion, Ohio University. Shooting 57% from the field, the 6’3” Notre Dame guard made 25 field goals out of 44 attempts. He nearly duplicated this amazing feat a week later against SEC champion Kentucky and Big Ten champ Iowa scoring 52 and 45 points respectively. His three-game shooting percentage was 58%. Significantly, he was joined by teammate Collis Jones who averaged 23 points per game in the three contests. Together, they produced 228 points in three successive tournament games – an average of 76 points per game on 54% marksmanship.

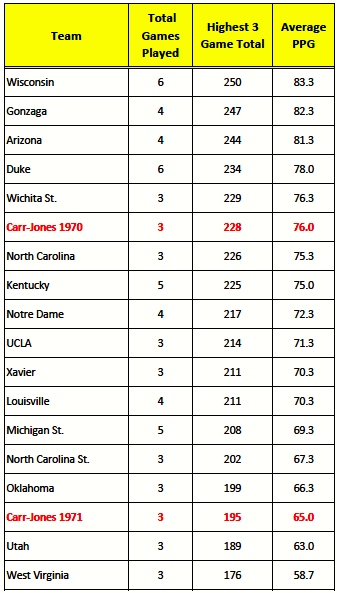

Only three teams out of this year’s field of 64 posted a greater points-per-game average – 80.5, 78.0, and 76.3. Think about that. Two players from an earlier era nearly outscored the entire field of 64 teams from today’s era.

Was this a one-year wonder? A statistical anomaly?

Let’s add one more year of tournament play to the comparison, three games in 1970-71. That year Carr and Jones combined for 195 points on 45% shooting, an average of 65 points per game. Over the course, then, of six games spanning two tournaments, the duo produced 423 points, shooting 50% from the field and averaging 71 points per game.

But it gets better… or worse.

Using only their three “highest scoring games,” how do this year’s “Sweet Sixteen” teams stack up against the Carr-Jones three-game performances? In other words, what happens when we throw out their lowest performances and average only their “best three”?

That’s a pretty dramatic picture of the state of today’s college game, a fitting proxy for the entire season, the forty-third in the long downward slide of college basketball from a game of fluidity, grace, and exciting offense to a game marked by wrestling, poor shooting and low scoring, control freak coaches, and interminable delay.

The decline is well known, documented repeatedly in a succession of articles and commentaries stretching back 15 years or more. Recently, though, the chorus of concern has grown louder and shriller, especially in the last several months. Here’s a representative sample:

- “This is a season of hopeless shots and streams of timeouts slaughtering any flow. One game was 17 – 14 at half and tied 55 to 55 after an overtime. Nine teams from power conferences have won games without breaking 50 points. Temple won a game scoring 40 points, on 11 of 48 shooting. Georgia Tech – an ACC program that gives out scholarships – scored 28 points… in a full, 40-minute game.” (Sam Mellinger, Kansas City Star)

- “I think the game is in crisis and I don’t think it’s in crisis just because of the final scores.” (Doug Gottlieb, CBS analyst)

- “I will fight for college basketball until the death but sitting by and watching this ship sink is not good enough. Who could defend what we are seeing right now? I love this game and it’s becoming unwatchable.” (Jay Bilas, ESPN analyst)

- “We allowed physicality and the weight room to become way more important that basketball skills. I think that led to an eroding of the game and not allowing basketball talent to come out.” (Curtis Shaw, Big 12 coordinator of officials)

- “I think the game’s a joke. It really is. I don’t coach it, I don’t play it, so I don’t understand all the ins and outs of it, but as a spectator… watching it, it’s a joke. There’s only like 10 teams in the top 25 that play the kind of basketball that you like to watch. And every coach will tell you there’s 90 million reasons for it. And the bottom line is, that nobody can score. They’ll tell you that it’s because of great defense, great scouting, a lot of film work … Nonsense. Nonsense.” (Geno Auriemma, Connecticut University women’s coach, defending national champions)

- “What a novel idea? Get the ball down the floor and score! Young coaches, get a tape of Loyola Marymount back in 1990… If you can score in the 70’s you’ll win a lot of games in today’s game of college basketball.” (Dan Dakich, ESPN analyst)

- “The pace is too slow. Bump and grind. Coaches micromanaging every possession. No flow. No freedom of movement.” (Seth Greenberg, ESPN analyst)

- “I have great concerns. The trends are long-term and unhealthy.” (Dan Gavitt, an NCAA men’s basketball vice president)

- “The product stinks …. We’ve accepted mediocrity.” (Tim Cluess, Iona head coach)

- “College basketball is facing a crisis … it stinks. It’s time for an extreme makeover.” Seth Davis, Sports Illustrated and CBS analyst)

- “NCAA men’s basketball is a brutal grind, a low-scoring, conservative game dominated by clampdown defense and half-court sets that look like they’re being run on wet sand… Field goal percentage is down. Possessions are down. Scoring is down to just over 67 points per game, its lowest level since the early 1950s, after declining in 13 of the last 15 seasons. Attendance is down. Turnovers are just about the only thing in college basketball that has recently gone up… A lot of basketball that feels like being slowly dissolved in the stomach of an anaconda. Virginia, probably the second-best team in the country over the course of the season, beat Syracuse earlier this month after scoring two points in the game’s first 13:53. Insert your own boilerplate acknowledgement that defense can be beautiful; does anyone seriously want to watch that? (Brian Phillips, ESPN)

- “If they want to keep kids in school and keep them from being pro players, they’re doing it the exact right way by having the 35-second shot clock and having the game look and officiated the way it is. It’s horrible. It’s ridiculous. It’s worse than high school. You’ve got 20 to 25 seconds of passing on the perimeter and then somebody goes and tries to make a play and do something stupid, and scoring’s gone down.” (Mark Cuban, Dallas Mavericks owner)

What to do about this mess? How to reverse the decline?

Next week the NCAA Men’s Basketball Rules Committee will meet to tackle these questions. They’ll come to the task armed with loads of analytic data and a long list of recommendations from their peers in the basketball community – widening the lane, shortening the shot clock, reducing the number of timeouts, lengthening the three point line, to name a few. But while such changes may be steps in the right direction, I doubt they’ll go far enough.

No one wishing to cross a wide ditch would attempt to cross half of it first but that’s exactly what’s likely to happen. By nature, committee work is characterized by courtesy, compromise, and concession. Very often the process trumps the outcome. In the committee’s zeal to reach consensus, it may end up with a plan that everyone can “settle for,” but no one feels strongly about.

For example, will the committee shorten the shot clock to 24 seconds to speed the pace of play or settle for 30 seconds in deference to coaches who insist that possessions must be long enough to accommodate a “variety of playing styles” (i.e., the coaching community’s incessant need to control every dribble)?

Will the committee look beyond good intentions and easy solutions to the unintended consequences that may follow?

Despite their best intentions the participants may find themselves behaving like the characters in the old fable, The Blind Men and the Elephant, each touching or “seeing” part of the problem from the limited perspective of the interest group he represents, no one touching or seeing the whole, or even if they do, lacking the authority to take the dramatic action required to really solve the problem.

Seeing the whole and taking the necessary action to reverse the decline in pace and scoring requires historical perspective and the willingness to grasp the confluence or intersection of factors that created the problem in the first place.

What we witnessed this past season was not an anomaly but the new norm – a style of play that has been in the making long before the shot clock and three-point shot were approved in the mid-eighties. The history of well-intentioned changes to open the floor and increase scoring have simply provided coaches with greater opportunity to do what they always do: micromanage.

Instead of an earlier era when some teams played slow, others fast, and still others at a medium pace, today we see a boring “sameness” – a series of four-minute t.v. segments further comprised of a series of 35-second possessions featuring largely ineffective, time-consuming screens set 20 feet or more from the basket in hopes of springing a dribbler free to attack the rim, or when denied, a pitch to a teammate for a three-pointer that will be missed nearly 70% of the time.

Walk back in time and you will discover just how bad this has been for the game. In 1960, Bobby Knight and his Ohio State teammates scored 90 points per game, still the school record. In 1970, Iowa averaged 103 points per contest in Big Ten play. That same season, sixteen years before the advent of the shot clock and the three-pointer, D-1 teams averaged 76.6 points per game. Forty-one years later we endured a 53-41 title game between UConn and Butler in which the teams combined for 26% from the field.

What the heck happened? Better defense? Better scouting and smarter coaches? Bigger and stronger players?

Let’s go back to where the problem started, move beyond the conventional wisdom, and untangle the real reasons for the decline.

Mark, I could not agree more. To be honest, outside of watching my daughter’s college team this year, the best exhibition of real college basketball was on the women’s side when the Dayton Flyers played UConn in the tournament. Best offensive execution and shooting I saw all year… men or women. On the men’s side – too many timeouts. Game is being too micromanaged.

Pretty impressive analysis cousin Mark….good stuff!

Coach: Great stuff. I am not a huge basketball fan as you know but your writing is so good it keeps my interest and even I can understand your points. You are the Roger Angell of basketball. As for the blog topic, I agree with Mr Schad that for pure basketball skills the women’s game seems far better and more fun to watch these days…Notre Dame being a great example.

Seebs. Great job. Accurate and on point. Requiring coaches to stay seated ala Coach Woden, is a start. Love your work. Doc

Just finished reading my first story written by Mark. What is really sad is that coaches still over-coach and the clock is still too long. Not to mention that officiating is just as bad as they refuse to grow a set and make some tough but correct calls without a worry about where they’ll work next year or will their tough calls eliminate them from tourney work. So now we’re embarking on the 2018-19 season and the idea is to let any ball handler initiate contact while driving to the basket and the poor defender gets whistled. Has anyone, including too many in the media, reread the rule book relative to guarding and screening? How about the part that talks about basic guarding principles? Now that my blood pressure is high it’s time to stop before I think about all of the reviews this comment will generate.

Tom, thanks for reading my post and making a comment. Anxious to see how this season’s “freedom of movement” rule interpretation works out. Like you I worry about the number of ticky-tack fouls being called, often breaking the natural flow and rhythm of the game. Generally, I’m pleased that a lot of the grabbing and mugging has stopped but hoping they can strike a reasonable balance. Guess I still favor my midwestern roots: No harm, no foul.

Pingback: Digging Deeper | better than a layup