At the tail end of last season, Jordan Sperber, analytics guru, blogger, and video coordinator for the New Mexico State University men’s basketball team, penned an insightful reflection on the concept of “offensive balance.”

Rather than retreating to conventional wisdom on the subject – the idealized notion that balanced scoring where everyone shares the ball and no one player dominates is inherently “better basketball” – Sperber dug deeper, revealing that it’s a bit more complicated than what the typical fan may imagine.

Using Loyola Chicago’s inspiring Final Four run as his starting point, Sperber constructed a statistical baseline, charting last season’s the top five scorers for every team in the country and developing a matrix to separate balanced squads from the unbalanced.

With his matrix in place he continued his exploration, probing the relationship between balanced scoring and offensive efficiency.

Are balanced teams in which scoring is shared somewhat equally among its starters more efficient than those where it is not? Is a team like Loyola Chicago whose starting five averaged between 11 and 13 points per man tougher to defend than a team like Oklahoma that relied significantly on the scoring prowess of its super star, Trae Young?

Sperber quickly dismissed the easy answer to this question, demonstrating that during the 2017-18 season “unbalanced offenses were actually slightly better than balanced offenses” for the simple reason that sheer talent trumps virtually everything else. Sportswriters and t.v. commentators romanticize balanced scoring but effective coaches identify talent and cater to it. As Michael Jordan once noted, “There’s no ‘I’ in ‘team,’ but there is in ‘win.’”

Sperber appropriately cited Davidson’s Bob McKillop as a prime example, a coach who loves motion offense because it epitomizes the concept of sharing the ball and spreading points across the line-up, yet whose squad last season ranked ninth-to-last in offensive balance. “In fact,” noted Sperber, “they’ve been an unbalanced scoring team for each of the past three seasons. The reason? Peyton Aldridge and Jack Gibbs…Coaching and scheme undoubtedly will play a role, but at the end of the day personnel is going to dictate scoring distribution dramatically… If you have South Dakota State’s personnel, you’re doing your offense a disservice by not featuring Mike Daum. If you have Gonzaga’s personnel, you’re doing your offense a disservice by not featuring your balance. Neither style is right or wrong, just different.”

Armed with this insight Sperber probed a more interesting and important question: “Are unbalanced teams (like Oklahoma) too dependent on getting good games from their best player?” What happens when the superstar on an unbalanced team has a bad night? Does this impact his team to a greater degree than when the top performer on a balanced team has an off night?

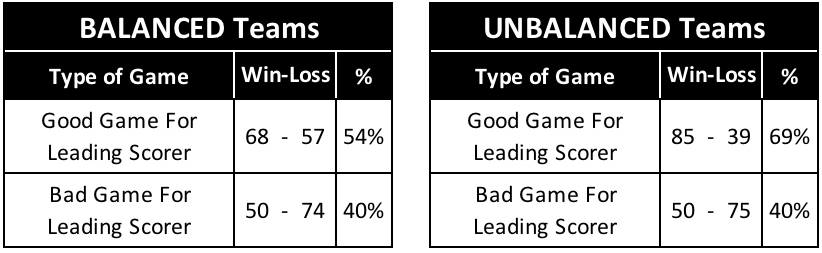

Sperber answered these questions in a simple but insightful chart:

Despite what is commonly believed, Sperber’s data reveals: (a) that high-volume scorers don’t play their unbalanced teams out of contention when they have a bad night any more than the top performers on balanced teams do; but (b) high-volume scorers definitely win more games for their teams when they have a great night.

In other words, all things being equal, a balanced team in which scoring is broadly distributed across its lineup faces the same level of risk when its top performer struggles as the unbalanced team does when its high-volume scorer has an off night. We tend to idealize the balanced team, cheering its “unselfishness,” but it’s equally vulnerable during an off night. A poor performance from a Clayton Custer threatens his team about the same as a poor performance from a high scoring Trae Young. “Balanced scoring” from the other members of the team generally won’t change the outcome.

Interestingly, Sperber’s conclusions are reinforced in dramatic fashion by two earlier Loyola Chicago squads, the 1963 national champions and the 1985 Sweet Sixteen edition. In both cases, Loyola featured balanced scoring teams whose top performers had difficult final games in the tournament, one sinking his team’s chances, the other pulling out victory with a furious charge in the final minutes of play.

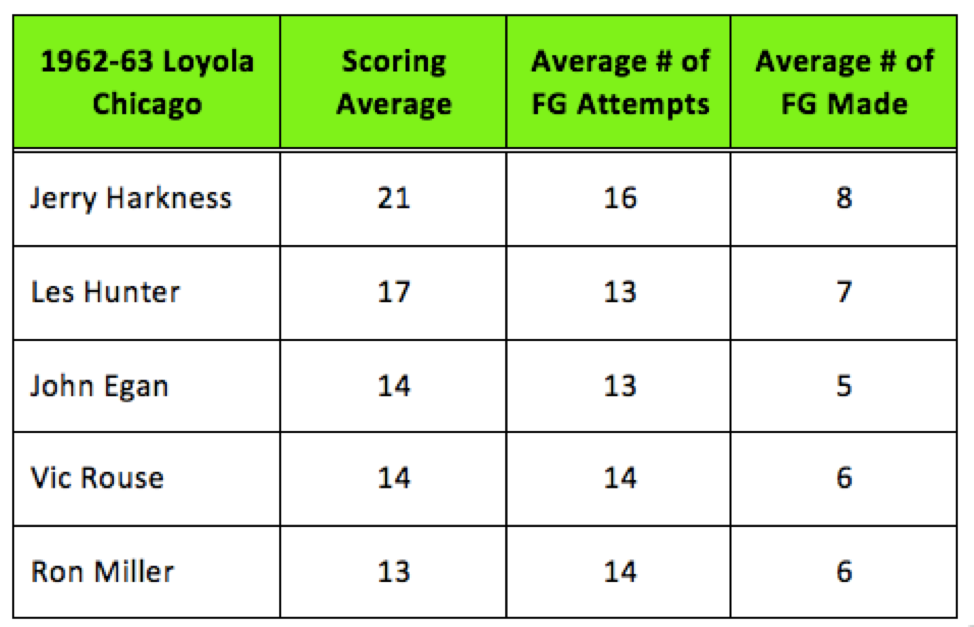

Here’s a look at Loyola’s 1963 championship squad.

From a statistical stand point the data is fascinatingly pure. Not only was scoring spread very evenly between the five starters, that season Loyola seldom substituted. During the season, the five starters accounted for 95.4% of the team’s total scoring. In its national championship game with Cincinnati, the starting five played the entire 40 minutes of regular play followed by a 5-minute overtime period. Not a single substitution.

The team’s top performer was Jerry Harkness, a consensus first-team All-American. During the championship game, though, he had a horrible night, scoring only a single point on a free throw during the first 35 minutes of play.

But, then, he exploded.

With 4:34 left in regulation, Harkness scored his first field goal, followed ten seconds later by a steal and a second basket. At the 2:45 mark he scored a third basket and with only four seconds left on the clock, he connected on a 12’ jumper to tie the game and send it into overtime. On the opening tip of the overtime period Harkness scored his fifth and final field goal.

In all, Harkness contributed 14 points in the victory, seven less than his season average, but enough in a low scoring game to help Loyola to overcome a 15-point deficit. In the course of 242 desperate seconds of play, he scored 13 of his points on five field goals and three free throws, propelling Loyola to the national championship.

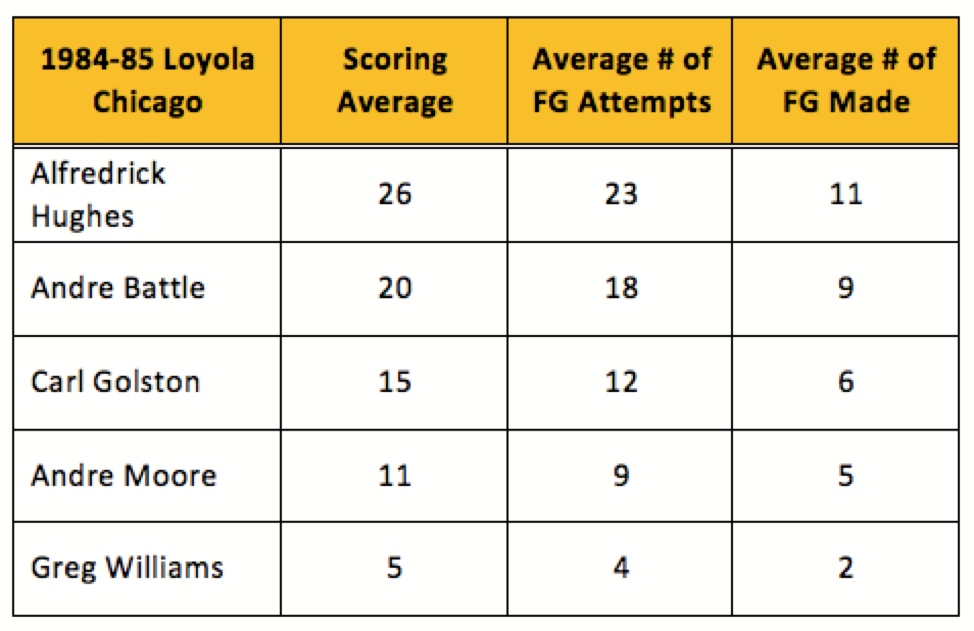

While Harkness was able to rescue his team with last minute heroics, Alfredrick Hughes, the top performer of the 1985 Sweet Sixteen Ramblers, did not a fare as well.

Like the ’63 Ramblers, Loyola entered the tournament as one of the nation’s highest scoring teams, a nation-leading 19-game winning streak, and a starting five featuring four players in double figures. Though not as balanced as the ’63 edition, the starting five accounted for 91% of the team’s total scoring with 85% of the team’s points running through the top four scorers.

After victories in the first two rounds of the tournament, Loyola found itself matched against Georgetown, the defending national champs. For the first 30 minutes the undersized Ramblers clung to a small lead but eventually succumbed to the Hoya’s superior depth and size, epitomized by 7’0” Patrick Ewing.

Unlike Harkness’ stunning comeback performance twenty-three years earlier, Alfredrick Hughes never got untracked. Beginning with his first field goal attempt that was blocked, Hughes had an absolutely dreadful night from the field, connecting on only four attempts – a total of 8 points, 18 fewer than his seasonal average. His “balanced” teammates simply did not have enough fire power to make up the difference.

Ironically, the ’85 Ramblers were coached by Gene Sullivan who served as the lead assistant at Notre Dame during the Austin Carr era. Ironic as both teams utilized the same offensive scheme – a helter-skelter break down the floor in hopes of gaining a numbers advantage, followed by Sullivan’s quick-hitting double stack half court attack – but while Loyola profited from relatively balanced scoring, Notre Dame’s success rested squarely on the high-scoring Carr and his teammate, Collis Jones. Together, during their junior and senior years, they accounted for 58 points or 63% of the team’s 91-point per game, regular season average.

Sullivan and head coach Johnny Dee weren’t interested in scoring balance, but in balancing offensive roles. They placed their starters in floor positions that were mutually supporting and played to each man’s strengths. Carr and Jones were great shooters, so by design they were expected to dominate the team in field goal attempts. In fact, once the post-season NCAA tournament began each year, the coaching staff sought to widen the scoring imbalance even further by increasing the tandem’s shot attempts.

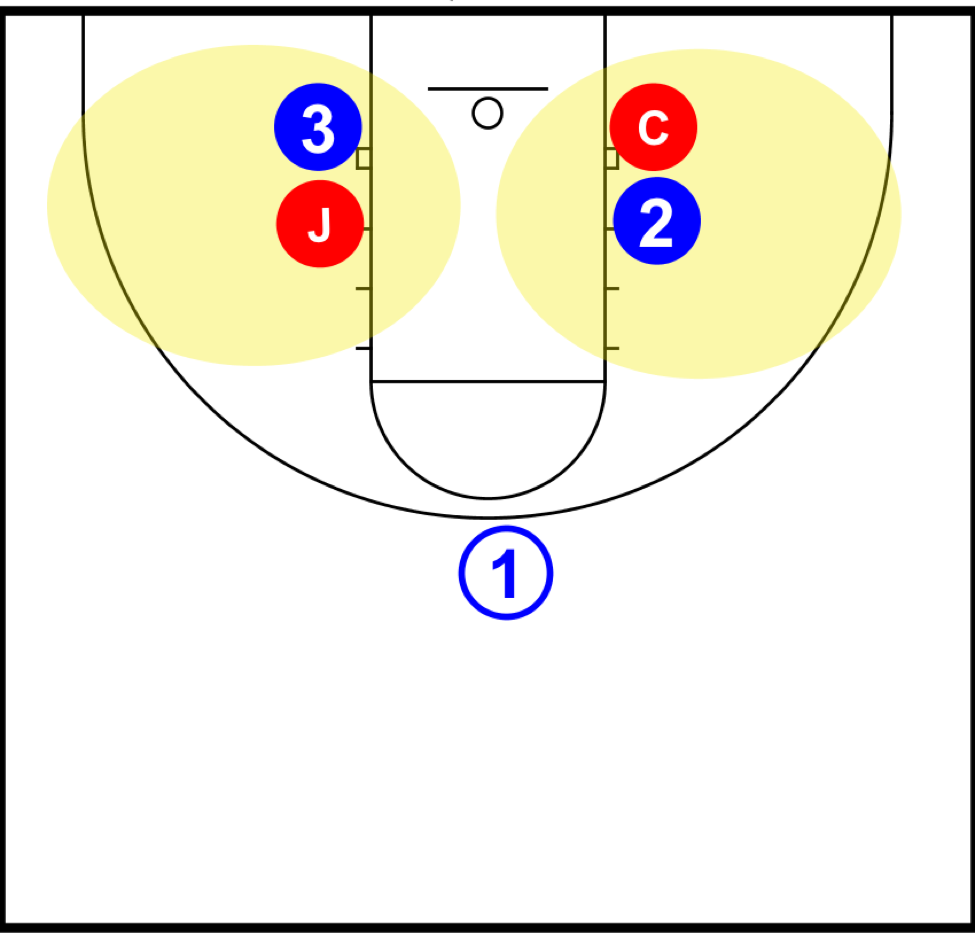

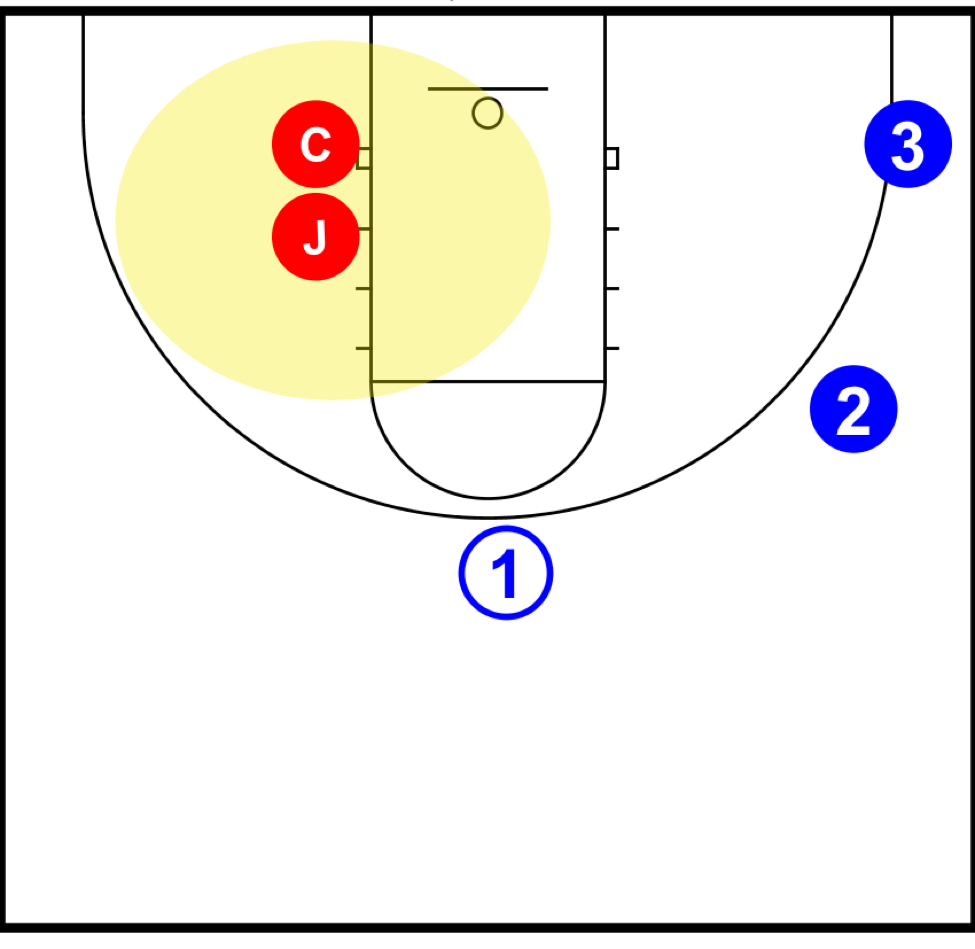

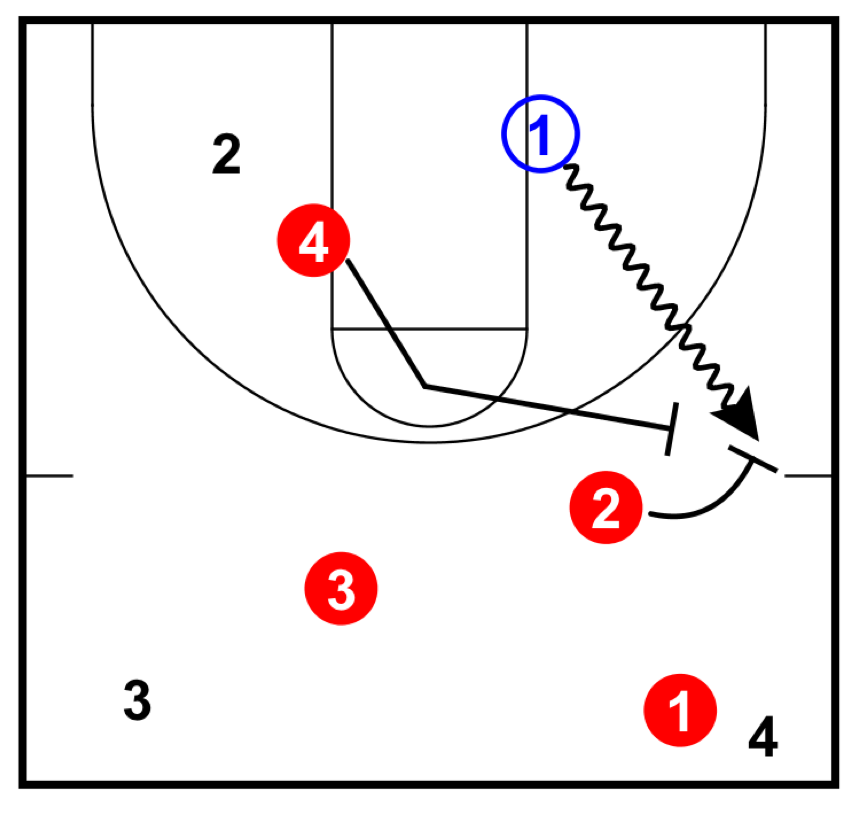

Throughout the regular 26-game season the Irish employed Sullivan’s double stack formation, placing Carr and Jones on opposite sides of the lane. This forced opponents to guard a wide perimeter making it difficult for them to help one another.

Throughout the regular 26-game season the Irish employed Sullivan’s double stack formation, placing Carr and Jones on opposite sides of the lane. This forced opponents to guard a wide perimeter making it difficult for them to help one another.

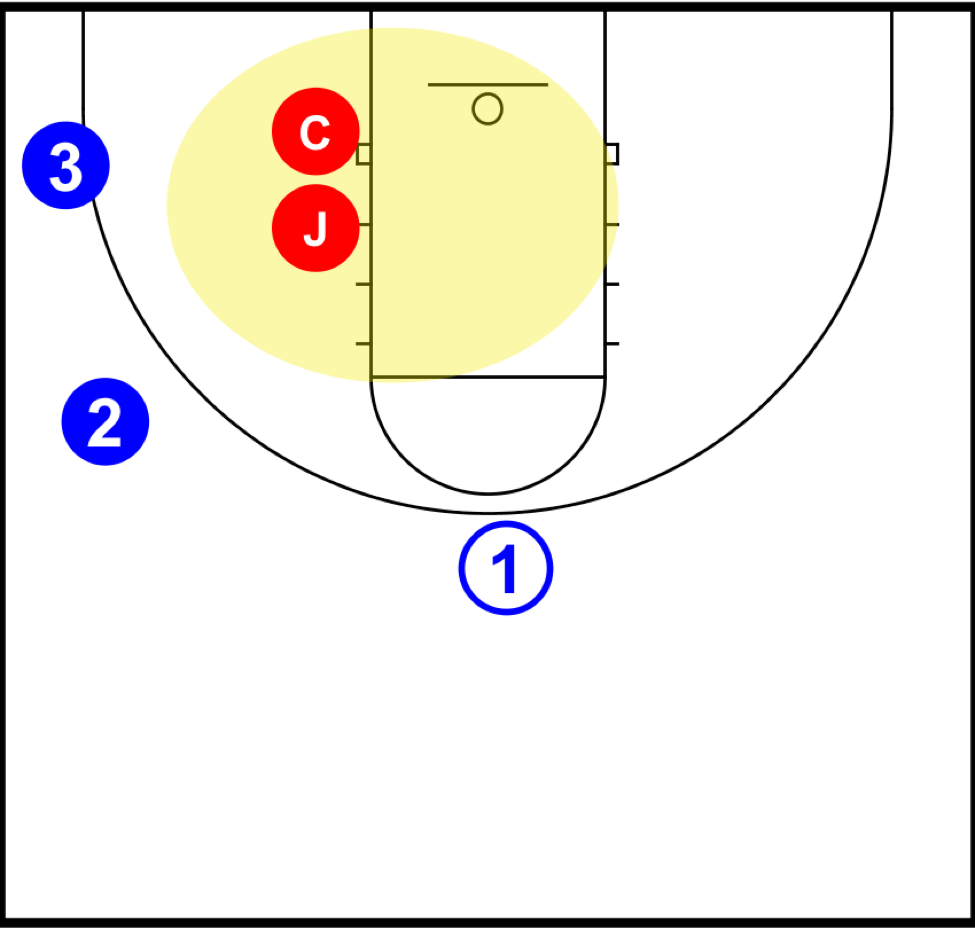

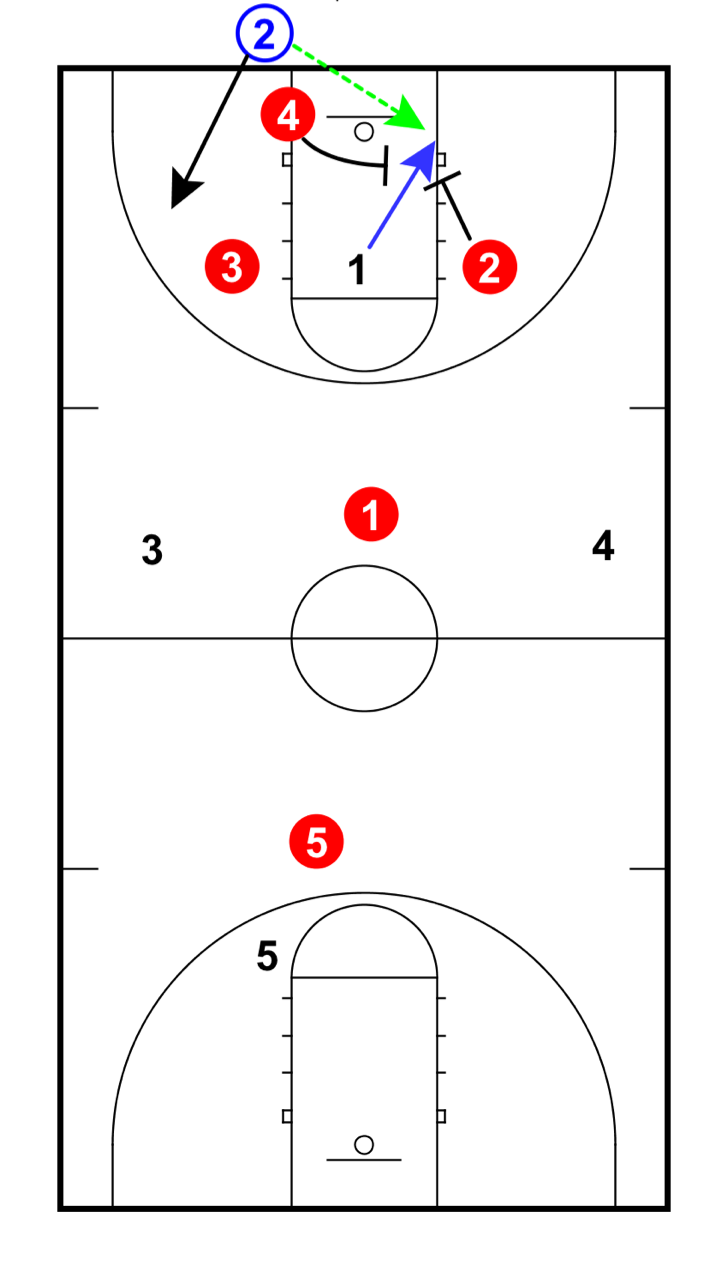

During the NCAA tournament, though, they shifted the point of the attack, employing a single stack with Carr and Jones aligned together on the left block, their teammates positioned on the other side of the floor, at the wing and corner. This created lots of room for Carr and Jones to maneuver and further isolated the defenders from one another.

The shift in alignment served as an accelerant. In effect, the coaching staff accentuated the team’s scoring imbalance in the belief that it would increase their chances of victory. Essentially, they played a two-man game.

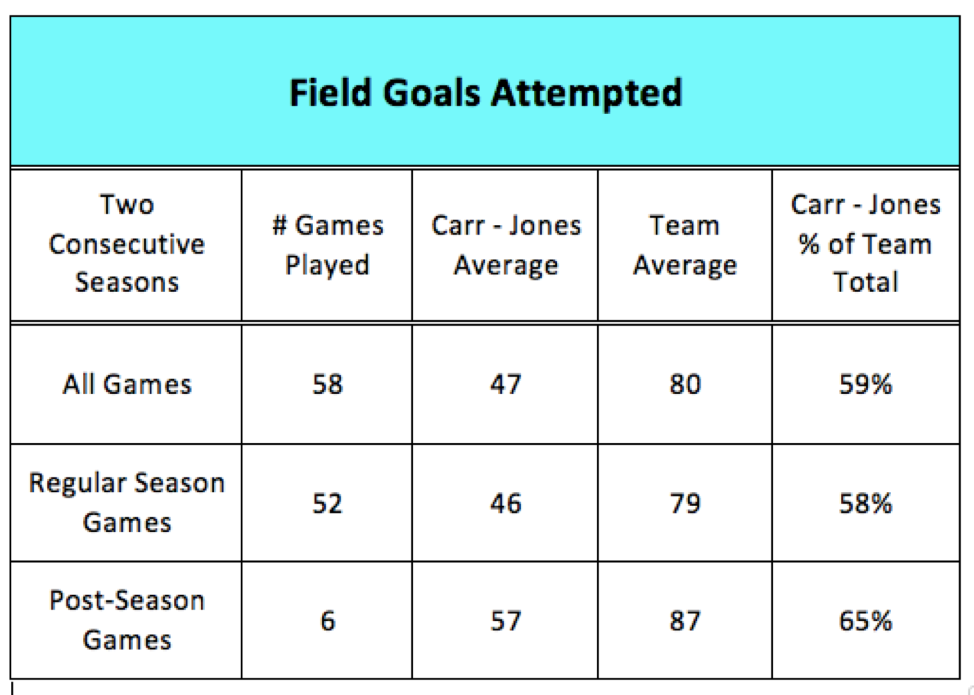

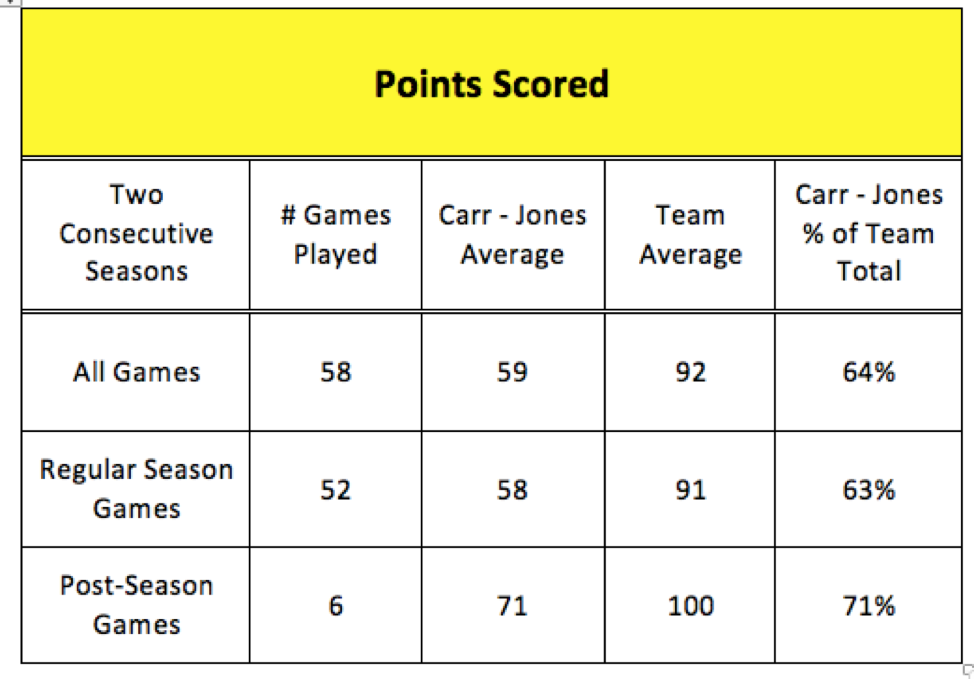

The following charts are instructive. Note the significant increase in shot attempts, points scored, and the percent of offense flowing through these two future NBA first-round draft choices.

Over the course of six games spanning two consecutive NCAA tournaments, Carr and Jones combined for 423 points, shooting 50% from the field and averaging 71 points per game. A two-man scoring record that has stood for nearly fifty years… and accomplished without the benefit of the three-pointer.

Sullivan’s experience at ND and Loyola provides an interesting bookend to Sperber’s findings on what constitutes balanced offense, for while he relied on unbalanced scoring at one school, he emphasized a more balanced approach at the other. To be sure, neither squad advanced past the Sweet Sixteen but both were among the top teams nationally in their respective eras. In fact, the ninth-ranked, 1970-71 Irish contingent was the only team that season to defeat UCLA on the way to its fifth consecutive championship.

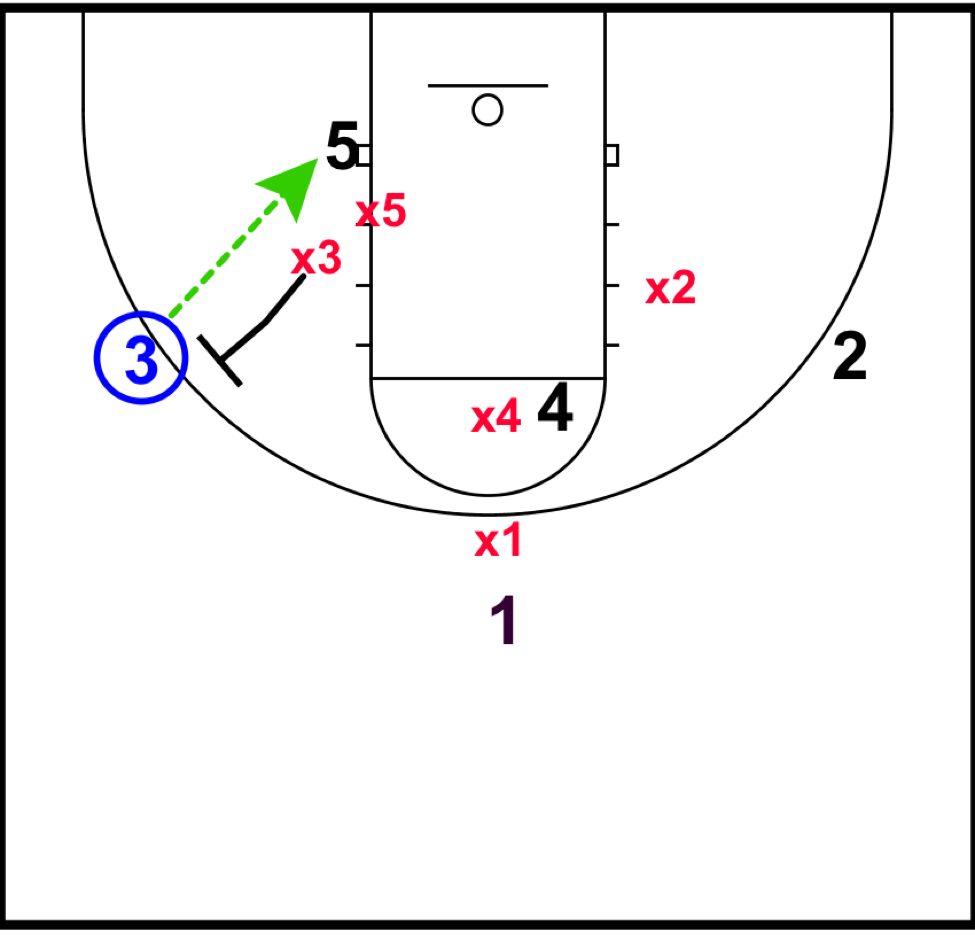

Sperber would not be surprised to learn that Carr and Jones had outstanding performances in that upset victory. Carr, in particular, was phenomenal. With 6:35 left, Notre Dame clinging to a four-point lead, the officials called timeout. Two important decisions were made at opposite ends of the court. On the UCLA bench, John Wooden switched defensive assignments, matching all-American Sidney Wicks on Carr; on the ND bench, coaches Dee and Sullivan shifted from their customary “double stack” alignment to an overload formation with Carr and Jones stacked together.

By isolating their two most potent scorers they hoped to increase their lead and seal the victory.

The result?

Carr scored 15 of Notre Dame’s final 17 points, in the process forcing Wicks into three quick fouls and out of the game, and leading the Irish to a decisive seven-point victory.

The lesson here is clear: good coaches measure their talent and position their players where they can be most effective, often times with little concern for achieving balanced scoring. Unsurprisingly, the legendary John Wooden presents us with several vivid examples.

In the fall of 1963, Wooden entered his 16thseason at UCLA, unranked and largely ignored. Thirty consecutive victories later, his Bruins forced 29 turnovers and beat Duke going away, 98 – 83, to win its first national crown. What happened to transform a likely mediocre season into such an eye-popping finale?

A change in fundamental strategy prompted by UCLA’s talented and quick, but very small starting lineup.

Throughout his career, Wooden had favored man-to-man pressure but during the offseason assistant coach Jerry Norman pestered him to replace his customary approach with a 2-2-1 full-court zone press. “We needed to do something different to force tempo and counteract our lack of size,” explained Norman years later. He convinced Wooden to use the zone press for the entire game, forcing opponents to play faster than they liked, leading to errant passes and turnovers, and a cascade of fast break baskets for the smaller but quicker Bruins. To spring the traps that anchored the defense, all-American guard Gail Goodrich played the front line paired with UCLA’s diminutive center, Fred Slaughter; the other guard, all-American Walt Hazzard played the backline with small forward, Keith Erickson, where they could pick off the frequently rushed and panicky passes. Together, they created sheer havoc.

The Bruin blitzkrieg produced a second national championship in 1964-65 season, then paused in 1965-66 while the extraordinarily talented freshman, Lew Alcindor, waited to begin his varsity eligibility. Then, Wooden unleashed two dramatic changes to UCLA’s strategy.

First, he shifted his 2-2-1 press to a “diamond-and-one” or 1-2-1-1 alignment to take advantage of Alcindor’s intimidating size at the defensive basket.

The 2-2-1 zone press is a very flexible defensive tool, creating opportunities to trap the ball at different spots in the backcourt as well as to vary the level of pressure, possession by possession. While the trap may be set immediately after the throw in, it often occurs above the free throw line extended, the defenders coaxing the ball handler up the floor and toward the sideline where he could be blocked on three sides, or on four sides if they sprang the trap as he crossed the midline. It’s a confusing press that often disguises its true intent.

While the trap may be set immediately after the throw in, it often occurs above the free throw line extended, the defenders coaxing the ball handler up the floor and toward the sideline where he could be blocked on three sides, or on four sides if they sprang the trap as he crossed the midline. It’s a confusing press that often disguises its true intent.

On the other hand, the diamond-and-one press is less confusing but more aggressive because the frontline defenders generally attempt to trap the ball immediately after the throw in, below the free throw line extended. Consequently, it’s more vulnerable than the 2-2-1 press because it commits three defenders to exert maximum pressure a long way from the basket they are defending. If the attackers beat this initial trap, they gain a three-on-two advantage very early in the possession.

But with 7’2” Alcindor guarding the basket, the Bruin’s defensive frontline could afford to gamble. They could attempt to smother the attackers at one end of the floor, confident that Alcindor would prevent any easy fast-break baskets at the other end.

But with 7’2” Alcindor guarding the basket, the Bruin’s defensive frontline could afford to gamble. They could attempt to smother the attackers at one end of the floor, confident that Alcindor would prevent any easy fast-break baskets at the other end.

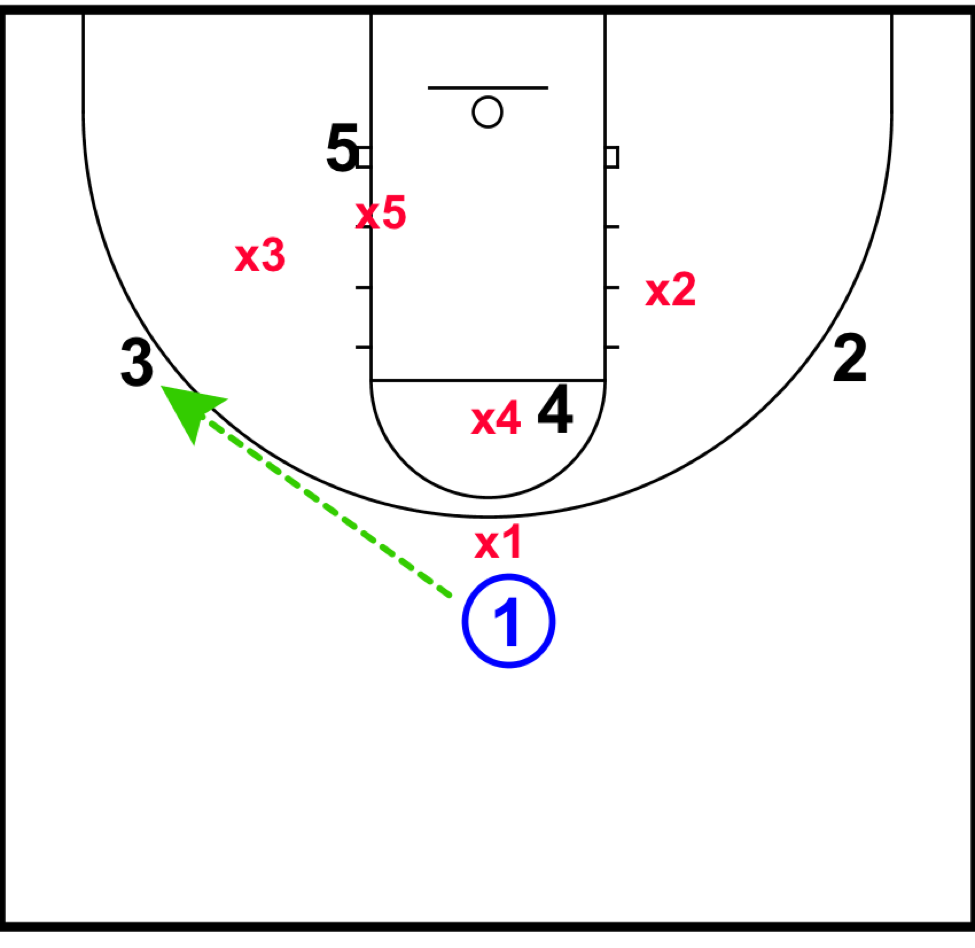

On offense, in response once again to Alcindor’s size and unusual abilities, Wooden made his second strategic change.  He shifted from his patented 2-1-2 high post offense to a 1-3-1 attack that positioned Alcindor on the left block near the basket with Lynn Shackelford, an excellent shooter from long-range, at the nearby wing. That placed the defense in a very vulnerable position, for whenever the ball was passed to Shackelford, they were forced to choose between two equally bad outcomes.

He shifted from his patented 2-1-2 high post offense to a 1-3-1 attack that positioned Alcindor on the left block near the basket with Lynn Shackelford, an excellent shooter from long-range, at the nearby wing. That placed the defense in a very vulnerable position, for whenever the ball was passed to Shackelford, they were forced to choose between two equally bad outcomes.

If Shackelford’s defender sagged to help cover Alcindor, Shackelford shot an easy jumper. If he contested  Shackelford, the ball went to Alcindor who was nearly impossible to defend one-on-one near the basket.

Shackelford, the ball went to Alcindor who was nearly impossible to defend one-on-one near the basket.

More significant than the change in offensive strategy was the choice of personnel to execute it. Long-time Wooden assistant Denny Crum, explains:

“You have to be able to get kids to take advantage of their strengths, but you also have to hide their weaknesses… other than Kareem, Sidney Wicks was our best player, but he didn’t even start. Who was in that spot, on Kareem’s side of the floor when he set up on the low post? Lynn Shackelford.

Why? Because if they tried to double-team Kareem, that left (Shackelford) open, and if they came out and guarded his (outside) shot, that left Kareem one-on-one. You put Sidney Wicks in that same spot, they wouldn’t guard him, because his percentage was poor. He didn’t accept that, so he kept shooting (the outside shot) . . . which is why he was on the bench.

Shackelford couldn’t run, couldn’t jump and couldn’t guard anybody, but on the offensive end, he was devastating. That was (Wooden) taking advantage of the strengths of his players.”

In the end, then, balanced scoring is really not the key indicator in achieving offensive balance at all; it’s just one of the many elements that coaches try to “harmonize” in response to the challenges of an entire season of play.

- What are the physical attributes of my team: size, strength, quickness of each player?

- What leadership intangibles will be in play this season? How many seniors do I have?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of each team member?

- What roles within our preferred offensive and defensive systems might best mask our weaknesses and accentuate our strengths? Should we consider fundamental changes to our preferred systems to accommodate the players we have? How flexible are we prepared to be?

- Who plays well together? Which combination of players assigned to specific roles seems to work best? Will that combination need to change based on the circumstances of a particular game or a particular point in the season?

Basically, it all comes down to the murky concept of chemistry. What pieces fit best together? The hardest part of coaching is recognizing the appropriate role for each player and determining how they will fit together, then convincing each player to surrender enough of his ego to make it work.

Excellent column Mark. A lot of times team chemistry is often only thought of as “how well do the players get along?” Team chemistry is more importantly built on fitting pieces of a puzzle together. Sometimes there is a dominant piece and sometimes all the pieces are more proportionate. Coaches need to find the answers to the questions you have posed above for each team each year. I think you also need to add to the mix: * Who wants the ball when times are tough or at crunch time. Who is willing to make the pass and who is willing and able to make the shot. And sometimes just as important… who does the team have confidence in to make the pass and the shot? The 85/86 Celtics as an example had a plethora of scorers and for the most part were a very balanced team. But when the game was on the line they wanted the ball in the hands of Larry Bird and everyone knew Danny Ainge would get it to him.

Again, great article Mark!

Thanks for reading and commenting, and most importantly, for adding a critical element to the concept. Your Celtics example is right on target.

Hi Mark—great stuff from great coaches. Thank you. I went to Pauley to watch practice one day and then to

the game that night — the year after Wooden retired with Cunningham now the coach. The press started as a 3-1-1 with the front three lined up across the free throw line, not pressuring the inbounds pass but waiting to double team the inbounds pass recipient. The idea was to force a pass with the other three defenders anticipating like football safeties ready to intercept. Same idea as Wooden’s press but the 3-1-1 made it easier to stop the ball and trap up the sidelines. It was fun to see UCLA practice. The first 40 minutes of practice didn’t include any coaches. The players ran fundamental drills — one of the drills was shooting bank shots from the side — 10-12 ft shots. Never understood that as most players would tell you the bank shot is tougher.

Thanks for reading my stuff, Chris. Imagine as you suggest that Cunningham wanted to delay the trap instead of immediately over-committing. By pulling the defender off the inbounder and aligning him further back with the two defensive wings he was able to play more of a cat-and-mouse game. Gave him less floor to cover. Love your observations about UCLA’s practice, especially practicing the bank shot. It’s a missing art. From the wing at short range in traffic, I actually find it easier to shoot. Back in the 60’s and 70’s I think a lot of players relied on it, perhaps not practicing it in a formal sense but routinely varying their practice shots between the rim and the backboard. Given Wooden’s emphasis on fundamentals I suspect that he purposely drilled his players in the technique and that his assistants like Cunningham continued the habit.