In my last post we explored the law of unintended consequences – that strange phenomenon that often occurs when we take an established routine or “way of doing things” – cutting the grass, driving to work, drafting a memo, playing a game, virtually anything – and change the routine or rules or circumstances under which the activity takes place.

Sometimes the change produces the outcome we desire; in other instances, the opposite occurs, often because the participants shift their behavior in unexpected ways in response to the initial change in routine. The well-intended result in one area often ripples into an unintended consequence in another.

I promised to explore how the law of unintended consequences has played out in the world of college basketball. Here goes.

Punctuating the history of college basketball are a dozen or more inflection points – milestone changes in rules, tactics, or societal circumstance that reshaped the behavior of players and coaches, in the process altering the nature of the game in both intended and unintended ways. Seven of these inflection points emerge as especially significant.

- Elimination of the jump ball after made free throws and field goals

The elimination of the jump ball after made baskets and free throws in the late 1930’s transformed basketball into a game of continuous action, the competitors converting from offense to defense and back again in near seamless fashion. Prior to the 1937-38 season, games came to a complete halt after every field goal, the teams gathering each time at midcourt for a jump ball to see who would claim the next possession. With this rule change basketball shifted from what too often descended into an endless contest of keep-away to a game of fluidity and grace that rewarded speed and agility as well as strength and size. From that point forward, basketball evolved as a game of transition.

- The rise of the jump shot

While the change in rules eliminating jump balls after made baskets insured that basketball would become a game of continuity and rhythm, a change in tactics a decade later cemented the new paradigm. The emergence of the jump shot in the late 1940’s followed by its rapid adoption across the country in the 1950’s liberated the offensive player to maneuver on his own. The jump shooter’s quick release combined with the height attained made it necessary for the defensive player to play much tighter than what was previously needed. The defender’s aggressiveness made him vulnerable to the fake and drive and, in particular, to a brand new maneuver — the lethal pull-up jumper. No longer would teams have to rely on intricate passing and patterned movement to free a shooter long enough to attempt a two-handed or one-handed set shot. Now players could catch and shoot while moving. Quickness became a player’s greatest asset.

- The unshackled bench coach

As the jump shot began to take hold placing a premium on quickness and freelance movement, coaches experienced their own form of liberation. For thirty-eight years, from 1910-11 through the 1947-48 season, bench coaching was not permitted by anybody connected with either team during “the progress of the game.” A warning was given for the first violation and a free throw awarded after that. During the 1948-49 season the coaching prohibition was lifted and for the first time coaches were allowed to speak to their players during timeouts.

For the next thirty-five years, the game continued to evolve largely as a “players’ game,” most coaches following John Wooden’s lead – teaching during practice and confining themselves to the bench during the game. To be sure, a select few used the rule change to work the refs, play to the crowd, and develop a media persona, but by and large coaches avoided the limelight. They used timeouts sparingly and limited sideline instruction to the essential lest they break the flow of the game.

But then a huge technological shift occurred and with it, the law of unintended consequences kicked in.

On Saturday, January 20, 1968 undefeated, top-ranked UCLA and Houston squared off in front of nearly 53,000 fans in the Houston Astrodome. Billed as the “the game of the century,” it was the first prime time, national telecast of a college basketball game in history, and is largely regarded as the most significant telecast in the history of the sport. From that point forward, television coverage of college basketball exploded. As I noted in a post last year, “the explosion of television coverage nationalized the game, helped standardize instruction, and dramatically popularized college basketball, but in the process, mythologized the role of the coach as the networks searched for an enduring, enticing narrative to exploit.”

Removing the restraints on bench coaching in one era, coupled with 24/7 television coverage in another, dramatically shifted the balance from a game focused primarily on players to one in which coaches became the center of attention. As the camera increasingly lingered on the antics of coaches strutting the sideline, the number of coaches, analysts, and timeouts seemed to multiply in proportion. Pace and scoring began to decline.

- Bully ball

Just as television coverage began to expand, another rule change took effect. In the early 1970’s the NCAA voted to eliminate the three feet of clearance required when setting a pick or screen. No longer were players obliged to allow space for the defender to get around the screen. Now they could march right up to the defender and physically block him. Bobby Knight, newly arrived at Indiana, looked for a way to take advantage of the rule change.

Early in his career Knight had favored an offense called “reverse action” – one of the many variations of the single-post style of play that had dominated the game since the mid-1950s. In this scheme, the attack unfolded from a triangular formation with a post player receiving an entry pass with his back to the basket followed by a move to the basket or pass to a teammate. “Reverse action” referred to the wing or forward cutting across the post man as the ball moved from side to side. It required refined footwork and lots of practice time to master the options that kept such an attack flowing.

In response to the new screening rule Knight replaced reverse action with a simpler attack he called the “motion” or “passing game” – a system in which the traditional positions of guard, forward and center were largely interchangeable. The old-style post game gave way to five players constantly passing, cutting, screening, and seeking open shots whenever and wherever the defense broke down.

At the same time, a momentous change was taking shape in American education. In 1972 Title IX became law, requiring schools and colleges to provide equal athletic opportunities for women. This meant that schools had to find a fairer and more equitable way to allocate practice time and thus, physical space. If a school only had one gym Title IX challenged it to find a way to accommodate both a boy’s program and a girl’s program. This usually meant limiting practice time. With less practice time available, high school coaches looked to install a simpler offense. Knight’s motion game provided the answer. Not only was Knight experiencing great success with his attack at Indiana, the passing game was easier and less time-consuming to teach. Intricate patterns of cutting, timing, and footwork gave way to a form of structured freelance in which players were taught a few simple rules to balance the floor and coordinate their movement, and then freed to read and react to what the defense gave them. Not only did it help solve the problem of limited facilities and teaching time, many coaches found the offense philosophically satisfying, as it required all players regardless of size to “learn the game” as opposed to “learning a particular position.”

As the motion offense grew in popularity several unintended consequences developed, one particularly hurtful to the game.

Traditionalists like the late Pete Newell, winner of the 1959 NCAA title at Cal and coach of the 1960 gold-medal-winning U.S. Olympic team (and a close friend and mentor to Bobby Knight) bemoaned the demise of post footwork and with it the disappearance of the big man. In his view, the motion offense clogged the middle resulting in fewer players who learned to make crisp, effective moves with the ball. Traditional footwork like the rocker step and the drop step that made such moves possible were seldom taught. “Footwork enables a player to get space to take a shot, and none of the foot skills we teach are part of the motion or flex,” Newell said. “It’s a shame to think that the next Kareem Abdul-Jabbar may be wasting away somewhere, setting screens.”

But more damaging than the demise of time-tested footwork was the increasing physicality demanded by the offense. The grinding action created by the constant cutting and screening relatively close to the basket forced the defense to respond in kind. Over time a kind of bully ball emerged with defenders clutching and bumping the attackers. This happened with such frequency that referees gradually began to ignore it and the mugging style of defense soon became the norm. The finesse and grace that had long characterized basketball gave way to a virtual scrum line.

By 1985, the NCAA and coaching community realized they had a problem on their hands.

They had seen their sport evolve from a stop-start-stop game controlled by coaches to a game of continuity and transition controlled by players. Eliminating the jump ball after each field goal meant they could no longer align their players around the midcourt circle, hoping to control the tip and begin their attack like a football team snapping the ball to launch a pre-designed play from the line of scrimmage. Instead, the change in rules insured that the game would unfold more randomly, driven largely by the players’ spontaneous decision-making.

A change in tactics – the development of the jump shot – forced coaches to surrender even more control. Whether they liked it or not, the read and react nature of the jump shot was simply too potent an offensive weapon to ignore. They could design set plays and patterns of movement but the moment of decision was truly in hands of players whose jump shooting ability freed them to maneuver on their own, literally changing the coach’s scripted play “on the fly.”

The rule change in 1948 to permit sideline coaching returned a small degree of control to the coaches but the game continued to progress through the 1950’s and 60’s as fundamentally a player’s game.

The happy consequence? An entertaining, ever-engaging spectacle: in the course of twenty-four seasons scoring increased by 25 points, from 53 PPG in 1947-48 to nearly 78 in 1970-71; shooting percentages steadily climbed as well from 29% to 44%; television coverage went national; the NCAA tournament blossomed into March Madness; coaching salaries, office pools, and interest in the college game soared.

But unexpectedly, in the midst of the game’s great ascent, scoring began to decline. By the end of the 1983-84 season it had fallen to 68 PPG, a 9-point decline from its high mark a decade earlier. The average number of field goal attempts and makes fell as well, from 68 to 56 and 30 to 27, respectively.

The cause?

Perhaps it was the rule change permitting more aggressive screening, leading unintentionally to the jiu-jitsu style defense that was now the vogue. Perhaps t.v. timeouts were the culprit, breaking the natural flow of the game, disrupting the pace, and consequently limiting possessions, shot attempts, and baskets. Or was the allure of the camera itself a contributing factor, rewarding the growing intrusiveness and sideline antics of the coaches? Perhaps it was a combination of all three, but whatever the cause, something had to give.

The NCAA turned to the NBA for answers. In 1985-86 they introduced a shot clock, followed a year later with a 3-point arc. Surprisingly, despite the momentous nature of these rule changes, neither produced its intended effect. Scoring continued its downward slide for another thirty years, culminating in a dreadful average of 67.7 PPG during the 2014-15 season, 61.2 PPG if you convert all field goals that season back to their original 2-point value. In other words, discount the inflation impact of the 3-pointer and the per-team, per-game scoring average declined by 17 points from its high back in 1970-71, forty-five seasons earlier.

How and why did this happen?

- The shot clock

Danny Biasone, owner of the old Syracuse Nationals, introduced the NBA’s 24-second clock in 1954 hoping to reverse low scoring, rough play, and declining attendance by stimulating offensive action. The typical NBA game produced 120 shots in 48 minutes or 2,880 seconds. To set the parameters for his proposed shot clock, Biasone simply divided the average number of seconds by the average number of shots. Thus, the 24-second shot clock. It immediately increased pace and rewarded fast-breaking teams like the Boston Celtics.

In 1985-86 the NCAA followed suit, introducing a 45-second shot clock. Eight years later, in 1993-94, they reduced the time limit to 35 seconds. In 2014-15 they reduced it again, to 30 seconds. The end result? Unlike the NBA, except for its first several years of existence, there was no appreciable increase in the pace of play or in scoring. In fact, things got worse.

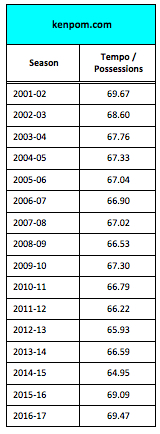

Ken Pomeroy, creator of the popular college basketball website and statistical archive, kenpom.com, began measuring tempo or pace of play back in 2001 by tracking each college team’s offensive possessions. Here’s a chart depicting his findings.

Note the steady decline in possessions despite the existence of the shot clock. Note particularly that the dramatic jump in 2015-16 when the shot clock was reduced to 30 seconds only elevated the number of possessions to the approximate level Pomeroy first documented in 2001-02. Round the numbers and you’ll discover that we’re still one possession shy of where we were sixteen years ago.

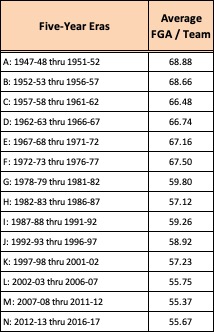

We don’t have tempo stats like this before 2001-02 because Pomeroy’s formula for calculating possessions depends on knowing a team’s offensive rebounds. Short of charting thousands of old game tapes that to a large extent no longer even exist, it’s impossible to apply Pomeroy’s tempo formula to past eras of college basketball. However, we can look at a simpler indicator of pace – field goal attempts – and draw some reasonable conclusions.

For the 30-season period extending from 1947 through 1977, pace of play was sufficient to produce an average of 68 field goal attempts per-team, per-game. During the next 40 seasons, pace slowed to a point that field goal attempts averaged only 57. To state the decline more starkly, that’s the difference between watching a game in which the opposing teams shoot the ball 136 times versus one in which they shoot 114 – 22 fewer shots attempts per game.

(Note: In 2005 Pomeroy attempted to calculate possessions for college basketball’s earlier eras based on data supplied by the NCAA. While conceding that his methodology was less exacting than his contemporary formula, he felt comfortable concluding that between 1948 and 1972, possessions generally hovered between the 80’s and low 90’s then declined sharply after 1972. Our analysis of shot attempts seems consistent with his findings.)

As Pomeroy himself speculated, the “denial and helping” defensive tactics that first emerged in the mid-1970’s and grew ever more aggressive in the years that followed are not enough to explain the drop in pace and shot production. “There’s a school of thought that the gradual slowing of the game is largely due to increasingly physical defense. But even without doing modeling, I think most people understand that the offense has more control over pace… The fact that they are taking longer to shoot appears to be mainly of their own free will… The shrinking of the shot clock will nudge some offenses out of their comfort zone, but for the most part the slowing trend in the game has been the offense’s responsibility.”

In other words, pace slowed because coaches adjusted their offensive tactics in response to the shot clock. Instead of speeding up as intended, they slowed down.

In effect, the shot clock broke the natural flow of the game by creating a series of artificially timed possessions or mini-games that coaches could manage, one at a time. The rise of modern analytics with its emphasis on measuring “efficiency” exacerbated the problem, as every possession became an opportunity to seek statistical purity. Add the multiplying effect of the three-pointer to the efficiency equation and frequent t.v. commercials to each coach’s personal allotment of timeouts, and the pace of the typical game could only move in one direction: downward.

Unwittingly, the NCAA contributed to the decline by adjusting the time constraints of the shot clock incrementally. This was done to balance the competing interests of its diverse membership, ranging from those who favored a fast-paced game to those who preferred ball control. While NBA had moved aggressively, setting tempo at 24-second intervals, the NCAA tinkered with the timeframe, adjusting the collegiate shot clock from 45 to 35 to 30 seconds over a thirty-year period. Instead of delivering the abrupt jolt the collegiate game needed, the rules committee went halfway and got halfway results. While the shot clock prevented teams from holding the ball in the final minutes of the game to protect a lead, it didn’t affect the overall flow of most games in any substantive way. Regardless of the particular time constraint, 45, 35, or even 30 seconds was still plenty of time for ball-control teams to slow the pace.

Oddly, the introduction of the three-pointer in 1986 – a rule change rewarding an extra point for baskets scored from a distance greater than 19’ 9”– amplified the unintended, dampening effects of the shot clock.

- The three-point shot

The NCAA implemented the three-pointer for two reasons: to generate dramatic comebacks and increase scoring. They believed that rewarding long jumpers with an extra point would challenge defenses to guard a wider perimeter, opening the floor for a more spontaneous, higher scoring game. The ploy succeeded spectacularly in one way but failed miserably in the other. While electrifying dunks and game-tying and winning threes came to dominate the highlight reel, scoring never regained the heights it had achieved in the early 1970’s.

Given the inescapable fact that three points count more than two, how is this possible? How can a game in which some field goals are worth more than others, coupled with the fact that today’s players are bigger, stronger, more mobile and athletic, produce fewer overall points than the distant past?

The answer is actually pretty simple.

In response to the three-pointer, coaches jettisoned traditional offensive schemes for new ones like the “dribble-drive” that fostered an either/or mentality: drive to the rim for a high percentage two-point layup or dunk, or pitch the ball outside the arc for a three-point attempt. Over time this led to lower scoring as teams passed up opportunities to shoot 12-foot jump shots in a time-consuming search for the dramatic dunk or three pointer. The shot clock merely defined the limits of the search.

Check out this clip from UNC’s victory over Arkansas in the second round of last spring’s NCAA tourney. Down by only one with 1:44 left, the Razorbacks squandered twenty-nine vital seconds aimlessly dribbling around the perimeter. They ended the possession with a 26’ heave as the shot clock wound down.

The unindicted co-conspirator in this tale is the coaching community’s growing obsession with modern analytics. Dribbling deeper and deeper into the shot clock means fewer possessions, fewer field goal attempts, and in the end, fewer points. But it also means higher efficiency scores – the meat and potatoes of the analytics movement.

Not only does “3” count more than “2,” a possession producing a three-point attempt is statistically more efficient than one resulting in a two-point attempt. The logic is simple: converting three shots out of ten attempts from beyond the arc beats four out of ten from inside the arc. Nine points beats eight; 33.3% beats 40%.

Once the shot clock was introduced, followed a year later by the three-pointer, is it surprising that coaches would begin playing possession by possession, relying more and more on three-point attempts to squeeze more efficiency out of each possession?

Clearly, efficiency is important. It means that you’re producing points each possession or in enough possessions to generate a statistical efficiency rating greater than your opponent. And, indeed, that often results in victory.

But not always.

The goal in basketball is to outscore your opponent by the end of the game, not to achieve a greater number of efficient possessions. It’s a bit like America’s presidential electoral system but in reverse. You win the presidency by accumulating 270 votes in the Electoral College where all fifty states are represented proportionally. The nationwide popular vote counts for nothing. In basketball the opposite occurs: the “popular vote” – the total number of points you score over the course of the whole game – means everything while the “electoral college” or points-per-possession means nothing. In the same way, the victor is not determined by the number of halves or quarters won but by the total number of points scored over the course of the complete game. In high school basketball you can outscore your opponent in each of the first three quarters only to get shell-lacked in the fourth quarter and lose the game.

A team posting a greater number of possessions, however inefficient, is often more effective because it generates more shot attempts than its opponent.

Witness the performance of West Virginia in this year’s NCAA tourney. Throughout the season the Mountaineers were an inconsistent, streaky shooting team. They marched all the way to the Sweet Sixteen, though, on the back of an old fashioned, interior-focused offense with lots of flex action, offensive rebounding, and intense full-court pressure that forced turnovers in nearly 28% of their opponent’s possessions. Though ranked a dismal 123rd in field goal percentage, they were 3rd in offensive rebounds, 5th in field goal attempts, and averaged ten more possessions per game than their opponents.

“The fact that they get way more field goal attempts than their opponents makes up for their very streaky shooting,” ESPN analyst Fran Fraschilla says. “I always say, ‘you have to create an offense with a missed shot in mind,’ because even if you shoot 45 percent from the field, 55 percent of the shots are coming off as misses… Their offense is designed with the missed shot in mind. In other words, they’re not worried about making or missing jump shots. If they go in, great. If guys heat up, great. But they’re also very cognizant of the fact that a missed shot [can be] a pass to a teammate. That’s how they look at it. You can analyze [the shooting] until the cows come home, but the fact is they get way more field goal attempts than their opponents.”

The old fashioned, but time-tested relationship between turnovers, offensive rebounds, possessions, and shot attempts still means something. Quantity often trumps quality.

Put aside the electrifying dunks and come-from-behind, long-range jumpers, and as CBS commentator and former coach Bill Raftery says, “The 3-pointer is a house of cards.” That same West Virginia team forgot its strengths, squandering its final possession in the tournament searching for the “efficient three.” Down by only three points with 38-seconds to go against Gonzaga, they jacked-up three successive three-point attempts and missed them all, burning the clock down to nothing in the process.

Contrast this with South Carolina’s victory over Florida the following weekend in the Elite Eight. Down by seven at half, the Gamecocks generated a 14-point swing, scoring 44 points without making a single three-pointer. In fact, they attempted only three in the second half, relying instead on “life in the paint” where they accumulated simple two-pointers and free throws. In contrast, Florida missed all of its fourteen three-pointers in the final 20-minutes of play.

Two seasons ago Villanova charmed the nation with its championship run, hoisting 44% of its shot attempts from beyond the arc during the season and defeating UNC in the final seconds with a dramatic three-pointer. Keep in mind, though, that the loser – UNC – returned to the final round last season, winning the national championship with its very traditional interior post game and offensive rebounding while three-point-crazy Villanova was bounced from the tournament in early March for the fourth time in five years.

If you’re hot from beyond the arc you’re very efficient and tough to beat, but on cold shooting night the “either/or” game leaves you with few alternatives.

Like Villanova most teams today have a no midrange game. In fact, several generations of players have come and gone without ever mastering a 12’ jumper or simple bank shot from the wing. The vast majority of today’s young coaches never played in the midrange themselves, have no knowledge of how to coach it, and are ignorant of the sets and schemes that produce it. Once today’s guards get into an area 10’- 15’ feet from the basket, they force their way to the rim and if denied, attempt to pitch the ball to the corner in hopes of a three-pointer. It’s all predetermined because they lack the confidence to pull up in traffic and hit the short jumper. There’s no third option.

Defenses, of course, are not stupid. As coaching consultant Randy Sherman recently posted, good defense invites the midrange pull-up by taking away the either/or game, forcing the attacker to take the one shot he is coached to avoid, he seldom practices, and has no confidence in making.

Refreshingly, during last spring’s NCAA tourney, commentator Jim Spanarkel sang the praises of the old school, midrange pull-up, explaining that even in the midst of the three-point era, it remains a potent weapon for those who have mastered it, and in fact, is an indispensable tool if one hopes to become truly “unguardable.”

If you doubt Spanarkel’s wisdom, imagine what will happen when the NCAA moves the three-point arc back once again… and you know they eventually will. The pool of players comfortable and proficient shooting threes from NBA distance will inevitably shrink and those left outside this special club will have no idea how to operate in the midrange.

In the end, not only did the three-pointer and the clock fail to increase pace and scoring to any substantive extent, they led to several unintended, systemic problems for the game.

First, poor shooting. Not just the inability of many players to maneuver and threaten the defense from the true midrange area (10’ – 15’ from the center of the cylinder), but a general decline in the art of shooting. There’s a reason so many NBA teams have hired shooting gurus to teach shooting mechanics. As SI’s Matt Norlander noted in 2014, “college basketball has become a game of scorers instead of shooters, and this has unquestionably downgraded the product.”

“I don’t think there’s any question that a fundamental like shooting is not being developed and taught like it used to,” says Fran Frascilla. “There are a lot of guys playing shooting guard at the college level who can’t make a jump shot.”

“Overall, the three has been good for our game,” said the late Rick Majerus following the disastrous 2011 final between Connecticut and Butler when Butler shot 18% from the field, “but that’s only when the right guys are taking those shots. You go into any gym now, and watch kids from 7 to 17, and they all gravitate to the three-point line. Even the kids who can’t shoot are out there throwing up threes. The middle game is gone… I always remember Don Haskins growling at one his players after he bricked a long jumper: Son, there’s a reason they aren’t covering you.”

How often do you see players take a simple bank shot from the wing? Coaches used to teach the value of the soft touch achieved through a high arc with backspin off the glass. Today it’s a lost art. “In the old days everybody used to shoot it off the glass. I can’t think of any young players who do it today,” says Pelican’s coach Alvin Gentry. “It’s old school,” chimes in former college and NBA star, Derek Harper, “and today if it’s not glamorous, it won’t work.”

“Guys don’t make any shots anymore, let alone bank shots. Guys today just want to dunk and shoot 3-pointers,” says Larry Bird. Walt Frazier agrees: “The art of shooting has been lost.”

Second, poor overall fundamentals. Add the rise of AAU and high school travel teams to the mix and the late Pete Newell’s lament that the sport is “over coached and under taught” is echoed by many observers.

John Jay, former Oregon State head coach and former assistant to master teacher Lute Olson: “Teaching nowadays is a matter of convenience. The demands for executing the right way aren’t as stringent. Now everybody wants to dunk or shoot the three, but nobody has the footwork to do the other stuff.”

Fran Fraschilla: “College basketball is about the incomplete player.”

Dan Peterson, former Delaware coach and twice coach-of-the-year during his fourteen years in Italy. “When I see NCAA players come here, I’m stunned. They have no moves, no shot, nothing to go to. They’re all looking for the spectacular dunk and have no interest in anything else. They’re always out of position, constantly taken to school by smarter European players. It’s embarrassing. The Italian federation used to invite an NCAA coach to its main clinic. They haven’t invited one for years.”

Donn Nelson, Dallas Mavericks president of basketball operations: “We’re getting kids who look at you as if you’re speaking a foreign language when you tell them to run a give-and-go. They’ve raced through the system on God-given talent. They spend two years in college for all the wrong reasons, and boom, land on NBA doorsteps. It’s a travesty. They can run and jump and dunk over you, but they can’t play five-man basketball.”

Frank Martin, South Carolina head coach: “I hear everyone coming up with every excuse possible why the game doesn’t flow. I think the shot clock is the last concern why it doesn’t flow. The NBA has a 24-second shot clock and I just watched an NBA team score 36 points in a half the other day. We’re talking playoffs, not a boring game at the end of January. Our problem is not with shot clock or defensive styles. Our problem is we’re under-teaching the game at the grassroots level.”

Third, waning team play and the lack of offensive diversity. The game used to be played off the pass, now it’s a game off the dribble. The off-ball screens that required movement without the ball have shifted to on-ball screens to set up the dribble-drive and the either/or style of play. Team A shoots and misses, forsakes the offensive rebound, and immediately falls back to prevent a run out. Team B snags the rebound, attempts the run out, and when denied, runs a high-ball screen to set up the dribble drive. More often than not, this results in one player dribbling, one screening, and three standing around hoping to receive a pitch out for an uncontested three. Everyone does the same thing.

Is there a way out of this mess? College basketball’s seventh historic inflection point provides an opening.

- Freedom of movement

Beginning in 2013-14 and extending over the next four seasons, the NCAA passed a series of rule changes and officiating “points of emphasis” to crack down on hand-checking, arm bars, and other forms of overly aggressive defense. The intent was to give offense room to breathe but in the face of increasing fouls and howling coaches during the initial months of implementation, the officials backed off, and bully-ball once again became the norm.

Two years later, during the 2015-16 season, the NCAA and coaches association tried again, this time successfully. The officials committed to enforcing the rules and points of emphasis with steadfast consistency. This time there would be no retreat. A foul is a foul is a foul. If you want to play tough defense, terrific, but from now on teach it the way we used to: move your feet, anticipate cutters, beat the dribbler to the spot, pressure your opponent all over the floor… but no more wrestling.

To further support the basic thrust of the movement, the NCAA expanded the three-foot arc under the basket to four feet, clarified block / charge situations, and even took aim at unfair offensive tendencies that had crept into the game like the mini-half step or hop that players were increasingly taking after receiving a pass, a disguised form of traveling.

Collectively these changes sought to grant both offensive and defensive players the floor space needed to make natural, normal basketball moves. And the effort has paid dividends, modest to be sure, but nevertheless positive. Since 2014-15 points per possession have increased by nearly a half point, effective FG percentage has climbed 1.5 points to 50.5%, and the number of free throws has declined by nearly two per game.

Is it enough? Not even close.

Dramatic action is required on three fronts, all of them aimed at the corralling the coaches and liberating the players:

- Severe reduction in the number of timeouts, especially during televised games. College coaches have more than enough time in practice to teach players to read game situations and apply the coaching staff’s preferred tactics on their own. Additionally, substitutions and simple hand and voice signals give coaches a means to manage the game without needlessly interrupting its flow.

- Stern enforcement of traditional bench decorum. Game officials must be granted the authority to police the sideline antics of coaches. The constant pacing, gesturing, and straying onto the court must come to an end. Such behavior seldom contributes to the outcome of the game except to reinforce the illusion that the coaches are more important than they actually are. The focus needs to shift from the “teachers” to the “students,” from the “directors” to the “performers.” (I was disappointed to see the NCAA expand the size of the coaching box for the 2017-18 season; they should dramatically reduce it.)

- Most importantly, a change in coaching philosophy and strategy emphasizing the open floor concepts epitomized by UCLA on the college level and Golden State in the professional ranks. “I watch and I think that this is the way basketball was played on the playgrounds,” says former NBA star Tom Mescherry in Sports Illustrated commenting on the Warriors’ style of play. “They pass, screen away, cut… it’s fluid.” Coaches are shameless copycats so perhaps this style will eventually spread. Right now, college basketball is like watching little kids play soccer: everyone runs to the ball. UCLA great Bill Walton explains how things used to be and why he is grateful that the Bruins returned to their old ways last season: “The rule at UCLA was that if you’re dribbling, you’re not dribbling to set yourself up… you’re dribbling to set someone else up. One dribble was OK… two, you’re passing the ball. There is so much mindless, senseless, and purposeless dribbling going on in today’s game.”

If you want a picture of what these changes would mean for college basketball, think one word: hockey. One time out, coaches standing behind the bench, rapid substitutions, constant movement.

Pass, cut, shoot. Pass, cut, shoot. Pass, cut, shoot. Pass, cut, shoot. Pass, cut…

Woah,this blog is amazing. I really like studying your content regularly.