Seems preposterous, doesn’t it? A jump shot is better than a layup?

How can a shot requiring you to leave your feet and launch the ball some distance from the basket – 8 feet or 15 or 22 feet or farther – be better than a shot taken close to the rim?

“Well,” you might answer, “it’s the three. Three points count more than two and that makes a 3-point jumper mathematically more “efficient” shot than a 2-point jumper… or even a layup.”

But you’d be wrong.

Like an accelerant added to a fire, the modern three-pointer plays a role but is not the determining factor. Instead, it’s the inherent nature of the jump shot that makes the proposition true, not the distance of the shot nor its relative value based on distance.

To understand, you have to go back to the game’s quaint beginnings in 1891 and trace the progression of rules, tactics, and innovations that culminated in the emergence of the jump shot in the early 1940s and its eventual wide-spread adoption in the early 1950s. Encyclopedic knowledge isn’t necessary but a cursory glance backward will help.

Historical Perspective

Punctuating the history of basketball are dozen or more inflection points – milestone changes in rules, tactics, societal conditions, or promotional initiatives, often in combination with one another – that shaped the behavior of players and coaches, in the process altering the nature of the game in both intended and unintended ways.

Most often these turning points were sparked by the action or influence of specific individuals.

For example, unlike baseball and football, we can literally trace the origins of basketball directly to one man and a time certain: James Naismith, early December, 1891.

In a similar vein, in 1929 the fledgling coaches’ association of the day voted to outlaw a tactic called “continuous dribbling.” Hoping to reaffirm Naismith’s original vision of the game by emphasizing team play characterized by coordinated passing and movement instead of individual maneuver, they limited dribbling to a single bounce after which the ball handler had to shoot or pass the ball. But CCNY’s coach Nat Holman lobbied the group to reconsider and vote again. Holman’s efforts carried the day and dribbling as we now know it was officially recognized as a legal tactic to advance the ball.

Jump ahead to 1968 when television promoter Eddie Einhorn secured the rights to syndicate the televised broadcast of undefeated, top-ranked UCLA and Houston squaring off in front of nearly 53,000 fans in the Houston Astrodome. He lined up 150 stations in 49 states throughout the country, some of them signing up on the day of the game. Billed as the “the game of the century,” it was the first prime time, national telecast of a college basketball game and is largely regarded as the most significant telecast in the history of the sport. From that point forward, television coverage of college basketball exploded.

From an historical perspective these and other inflection points fall into six loosely defined time periods or phases, each characterized by one or more general trends:

• Origins & Growing Pains, 1891 – 1919: Naismith’s vision and defining structure of the game; how early experimentation refined his original 13 rules and standardized the basket and backboard, the number of players, and the dimensions of the court.

• Rise of the Coaching Fraternity, 1920 – 1932: Expansion of the game into different regions under the direction of an emerging group of “professional” coaches who sought to brand the game with their own unique styles and strategies.

• Paradigm Shift, 1933 – 1950: A seventeen-year stretch of tremendous ferment during which basketball’s regional, parochial nature gives way to a truly national game; sportswriter Edward “Ned” Irish begins promoting college double-headers in Madison Square Garden, attracting teams from the mid and far west regions of the nation, exposing the game’s fan base and coaches to different styles of play; the center jump after every score is eliminated leading to a game of continuous action and greater scoring; the two-handed set shot gives way to the jump shot; the first NIT and NCAA tournaments are played; the 1936 Olympics followed by WWII spreads basketball across the globe.

• The Modern Game, 1951 – 1978: Basketball’s coming-of-age period; the jump shot becomes the game’s primary offensive weapon; NCAA scoring climbs dramatically, increasing an average of 15 points per game by 1971; stylish inner-city black players popularize “urban cool,” slam dunking, and one-on-one freelance; Mississippi State challenges the southern color barrier, sneaking across state lines to play an integrated Loyola Chicago team in the 1963 NCAA tournament, followed three years later when Texas Western starts five blacks against Kentucky’s all-white lineup and wins the national championship; nationally televised college games become a regular feature on the major networks; UCLA’s John Wooden wins ten national titles in twelve years; Larry Bird squares off against Magic Johnson in the 1978-79 NCAA championship game, cementing the tournament’s growing prominence.

• March Madness, 1979 – 2000: ESPN debuts and the number of regional and national telecasts of college basketball explodes; the NCAA tournament expands to 64 teams and the tournament quickly rivals the Super Bowl and World Series as America’s premier sporting event; introduction of the 3-pointer and shot clock; North Carolina freshman Michael Jordan hits the winning basket in the 1982 national championship and soon becomes the iconic figure of the NBA; one of only three basketball coaches to win an NCAA title, NIT title, and an Olympic gold medal, Indiana’s Bob Knight is fired after decades of controversial sideline and off-the-court behavior.

• Conflict & Uncertainty in the Midst of Soaring Popularity, 2001 – 2022: Every tournament game broadcast in its entirety; the 3-point line is moved back twice and the shot clock reduced to 30 seconds; the rise of AAU, high school travel teams, and the decline of fundamentals; the rise of analytics, positionless basketball, and death of the big man; amateurism questioned as NIL, pay-for-play, transfer portal, and soaring coaching salaries dominate the headlines; the COVID pandemic cancels the 2019-20 tournament; the unintended consequences of the 3-pt shot explored; the NBA’s financial ties to communist China sharply criticized; college basketball’s winningest coach, Mike Krzyzewski retires.

To be sure, these time periods are arbitrary, overlapping and irregular, subject to debate depending on how one chooses to divide the game’s historical chapters.

Generally, though, regardless of how one defines the timeline, we find that basketball’s entire 132-year evolution turns fundamentally on just three events set in the mid-1930s, roughly a third of the way through the tale.

Crossing the Rubicon

That they occurred almost simultaneously is an accident of history but given their impact on the game we play today, they are intrinsically linked. Before, basketball was one kind of game; after, it was something altogether different. Once they took hold, the game crossed the proverbial Rubicon. There was no going back.

The first surfaced in dramatic fashion in 1936 when the game’s customary two-handed set shot collided with a one-handed, running “push” shot pioneered by Stanford’s Hank Luisetti. The second, a season later in 1937 when the Collegiate Joint Rules Committee eliminated the mandatory jump ball at center court following each field goal. Setting the stage for both was the third innovation – the brainchild of New York City sportswriter Edward “Ned” Irish – an annual series of double and triple-headers in New York’s Madison Square Garden that attracted the best teams from across the country, exposing thousands of fans, sportswriters, coaches, and players to different styles of play that challenged their preconceived notions of how the game should be played.

Taken together, the three were stepping stones to the modern game of basketball.

Eliminating the repetitive, time-wasting walk to the center of the court for a jump ball after each score produced a game of transition as teams seesawed in near seamless fashion from offense to defense and back again. Paired with Luisetti’s new style of shooting-on-the-move, the game sped up, producing more possessions, shot attempts, and scoring. And Ned Irish’s promotional efforts in New York City, the sports mecca of America, showcased this new way of playing for the entire nation. Overnight basketball’s popularity soared. Two years later, Irish engineered the formation of the National Invitation Tournament, America’s first post-season, single-elimination championship. And, in 1939, the National Collegiate Athletic Association responded by playing its own “official” championship.

Basketball’s founder, Dr. James Naismith, lived long enough to see it all – he died in late 1939 – but, by all accounts, was surely surprised by the game’s growing prominence.

He never set out to invent such a game, never had any aspirations for it or himself as the game’s inventor, when in early December 1891 his boss at the YMCA training school in Springfield, Massachusetts challenged him to win over a restless class of future Y executives by concocting a new game that could be played indoors. At the time, Naismith never imagined inter-scholastic competitions in front of large crowds of 15,000 or more, national championships, and paid professional coaches designing strategies, organizing formal practices, and managing games from the sideline.

Instead, he saw his task as little more than creating a simple diversion to keep his students in shape and engaged during the cruel northeast winters while avoiding the natural roughhousing of outdoor games they enjoyed like rugby and football. To that end he spent two fruitless weeks trying different indoor adaptations of soccer, lacrosse, and football. What emerged was a loosely organized game of keep-away characterized by pushing, shoving, tackling, an occasional broken window… and a class of bored, increasingly cynical students. The very things he sought to avoid.

Finally, during a fitful evening of brainstorming shortly before Christmas break, Naismith had his epiphany.

To eliminate tackling, he would outlaw running with the ball. Instead of carrying the ball, players would have to pass it… but to what end? He needed an objective, a way for players to score points as a result of their passing and “win the game.” In football and rugby, you carried the ball across a goal line to score; in soccer, hockey, and lacrosse, you kicked or hit the ball with a stick into a goal. But in each of those games, players inevitably converged on the target leading once again to the collisions, pushing, and shoving Naismith was trying to avoid.

His solution? Place the goal above the playing surface, requiring the players to throw or shoot the ball over their opponents instead of running through them.

Early the next morning he turned his imagined game into reality. In less than an hour, he composed thirteen rules, thumbtacked them to a bulletin board outside the gym, and instructed a janitor to mount two peach baskets to the gymnasium balcony, one at each end of the court. At 11:30 AM, his students flocked into the gym, divided into two teams of nine, and armed with a soccer ball began playing a game that Naismith had not yet even named.

It was an immediate hit.

Despite excessive fouling and only one goal, Naismith left the gym pleased. “The only difficulty I had was to drive them out when the hour closed,” he later recalled. After Christmas break, at the urging of one of his students, Naismith finally christened it. At the top of the paper listing his rules he scribbled two words – “Basket Ball.”

The Early Coaching Fraternity & Regional Styles of Play

Not surprising, the game quickly evolved as Naismith’s students improvised, bending and reshaping his original thirteen rules to their own desires, improving the game as they went.

For example, Naismith envisioned a game in which the ball was continually passed from one player to the next until they got it close enough to the basket to take an effective shot. Since there was no other way to move the ball from player to player or spot to spot except by passing, clever players began “passing it to themselves.” The player in possession of the ball rolled or threw it to an open spot on the floor, then tried to outrun his defender to recover it. This so-called “air dribble” soon morphed into the modern “dribble,” bouncing the ball in repetitive fashion as you moved across the court. Similarly, players invented a footwork tactic called “pivoting” to parry a tight defender – moving one foot while keeping the other anchored to the floor. Like dribbling, this created the space needed to pass or shoot the ball without violating Naismith’s keystone rule that prevented “traveling” or carrying the ball.

In many ways, Naismith’s thirteen rules formed a “rough copy” that invited, if not demanded, revision as the act of playing the game collided with the imprecision of the original rules. While innovations like pivoting and dribbling liberated players to evade defenders and maneuver more easily for a shot, rules standardizing the dimensions of the basket, backboard, and ball, how time and scoring was kept, the number of players, and those establishing the court’s basic layout and boundary lines provided the constraints necessary for fair competition.

Over time, as Naismith’s students graduated and took up positions in the network of YMCA organizations around the country, they took basketball with them, forcing definition on the game through trial and error, in the process, seeding the first generation of professional coaches.

Prior to WWI, coaching was largely a “delegated chore” assigned to PE teachers or members of the football staff during their offseason. Even Naismith, after moving to the University of Kanas in 1898 to head its PE department and become the school’s first basketball coach, saw himself as a mere supervisor or moderator, setting up schedules with rival schools but often refereeing games in place of managing his team from the sideline. He held only occasional formal practices and seldom traveled with his team. Just as he had attached little significance to basketball when he invented it, Naismith never saw it as a game that could be seasoned, strategized, and coached. He took no genuine interest in winning. Indicative of his approach, he lost his first game to Nebraska 48 – 8 and is the only coach in the university’s long distinguished basketball history to have a losing record.

Fortuitously, Naismith’s dismissive approach to coaching triggered the opposite response from one of his players, Forrest “Phog” Allen, who was so entranced by the game and its potential that he stayed at Kansas after graduation to become Naismith’s assistant. They seldom saw eye to eye on anything. For Naismith, basketball remained an informal game best left in the hands of the players, while for Allen it was an exacting science that could be mastered and taught to others. He insisted that one could teach players “to pass at angles and run in curves,” that one could strategize and coach a style of play that led to proficiency and victories.

Whatever their differences, sitting on the bench side by side with the game’s inventor for nine years conferred stature on Allen and when he took over the Kansas program in 1920, he used it as a platform to promote the game, building stability and professionalism in the coaching ranks.

Over the course of 39 seasons, he accumulated 746 victories, 24 conference championships, 2 Helms Foundation national championships, the 1952 NCAA championship, founded the National Association of Basketball Coaches, and was the leading proponent to make basketball an official Olympic sport in the 1936 Games.

Perhaps most importantly, Allen spawned a generation of coaches who put their own unique marks on the game.

Walter Meanwell, Nat Holman, Everett Dean, Clair Bee, Ward “Piggy” Lambert, Doc Carlson, Sam Barry, Nibs Price, and a small cadre of others were the game’s early coaching pioneers. They were a diverse group, relatively isolated from one another by America’s vastness with few opportunities for intersectional games, leading naturally to regional differences in strategy and styles of play.

In the East coaches favored deliberate passing, intricate weaves, and high percentage two-handed shooting. In the West – basically anywhere west of Pittsburgh – play was less structured and more experimental with one-handed shooting in the pivot area and early attempts to define fast-break tactics. But overall, regardless of region and style, the game remained slow-paced with little sustained action and painfully little scoring.

Recall that this was an era when every score resulted in the players parading to center court for a jump ball to initiate the next possession while the game clock kept running. Not only did this interrupt the flow of the game, it meant fewer possessions and lower scoring because as much as 12 minutes of playing time – nearly one-quarter of the game – was lost in the process.

On top of that, many teams, especially those in the East, succeeded by stalling – passing the ball back and forth for long stretches of time at the far end of the court until a perfect uncontested layup or set shot emerged as there was no backcourt rule to prevent it. This changed in 1932 when two westerners – Southern Cal’s Sam Barry and Nibs Price of University of California – petitioned their colleagues to establish a half-court line to distinguish the front court from the backcourt, and a 10-second rule requiring the ball to move into front court within ten seconds of beginning a possession.

While these rule changes forced teams to attack the defense in the half court instead of playing a waiting game in the backcourt, the broad stylistic differences between East and West were actually reinforced. Each style now had to contend with the fact that the space in which offensive action took place had effectively been cut in half; once the ball crossed the midcourt it had to remain there, so the defense had less space to contest. They could “mass” their defenders in a tight man-for-man defense near the basket or play a zone to nullify the elaborately scripted cutting and passing so many coaches relied upon to generate open layups and perimeter set shots.

Western teams countered with fresh emphasis on their fast-breaking schemes, rushing five men down the floor before the defense could get set. “When a successful fast break is obtained, the mass principle of zone defense is destroyed,” counseled Purdue’s Piggy Lambert whose squad was led by an extraordinary guard named John Wooden and whose offense depended “on the initiative of the players rather than set formations.” Lambert’s race horse attack was not the only strategy employed in the West but it epitomized the more open, player-directed, freelance style favored by coaches who worked in the small towns, farm communities, and the new green world of California, far from the reflexive orthodoxy of basketball in the big cities on America’s eastern seaboard.

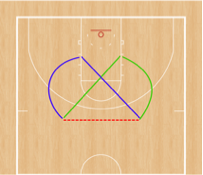

In the East, of course, coaches dismissed Lambert and his western cohorts as heretics, insisting that their plodding, deliberate approach to the game, demanding team work, patience, and disciplined ball control was the only proper way to play the game. They shot the ball in the traditional two-handed manner, and rarely shot at all until the ball had been worked in with a half dozen passes or more. NCCY’s Nat Holman ran the “Holman Wheel,” all five players cutting and swerving through endless loops around the basket until an uncontested shot emerged, while in Pittsburgh Henry Carlson used a complex weave that resembled a Figure 8.

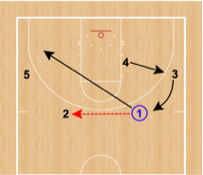

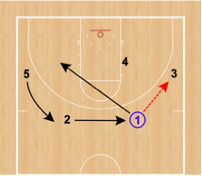

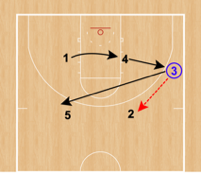

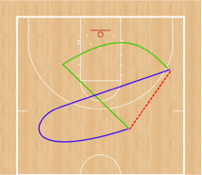

Carlson created continuity by cutting the players through the front court using three different pathways: crosswise beginning with a guard-to-guard pass; vertically with passing between a guard and a forward; diagonally by passing and cutting players from one corner to the other. The direction of each pass triggered the resulting cutting pathway and the movement from one position to the next formed a Figure 8. Scoring opportunities surfaced whenever the defense broke down.

Here’s the crosswise pattern followed by an image illustrating the emerging Figure 8.

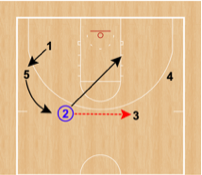

Carlson’s vertical pathway unfolded like this.

Carlson drilled his players in these basic continuities as well as the diagonal version, then intermixed them, and finally schooled them to see the natural “breaks” in the pattern where they could score.

To be sure, the stylistic divide between East and West was by no means absolute. New Englander Frank Keaney jettisoned the slow-poke offenses of NYC in 1928, instructing his Rhode Island teams to rush down the floor to create a numbers advantage and attempt more shots that their opponents. Eleven hundred miles west, Wisconsin’s coach Doc Meanwell ran a disciplined, ball control system he called “scientific basketball,” built on criss-cross cutting patterns, short passes, and limited dribbling, just like they did in the East.

But the general trend held true.

The confined quarters of NYC and the eastern seaboard seemed to promote rigid conformity to slower, methodical strategies while the vastness of the Midwest and West, its towns and schools often miles apart, led to experimentation, variety, and a freer style of play.

On December 30, 1936 these two styles of play collided in dramatic fashion when Stanford squared off against Long Island University in one of Ned Irish’s famed double-headers at Madison Square Garden.

Collision

Irish had begun promoting double and triple headers matching local teams with showcase teams from around the country five years earlier in 1931. Within a few years he was sponsoring as many as eight extravaganzas per season featuring big name programs like St. John’s, NYU, CCNY, Notre Dame, Kentucky, Oklahoma State, Loyola Chicago, Bradley, Cal Berkeley and Stanford, and attracting huge crowds of 16,000 or more to the Garden. In less than a decade he had made New York City the mecca of college basketball.

Stanford’s arrival in town that December was met with anticipation but also a good bit of skepticism, if not derision. They were defending champions of the Pacific Coast Conference but the year before, NYU had trounced a University of California team that had split four games with Stanford during the conference season. And now Stanford was matched with the class of eastern basketball, Clair Bee’s Long Island University of Brooklyn, winners of 43 consecutive games against the best teams of the nation.

While LIU was a known commodity to local fans and the press, Stanford was an enigma. In their pre-game workouts, they seemed to approach “the epochal conflict between Eastern orthodoxy and Western iconoclasm with an attitude bordering on the frivolous,” noted Sports Illustrated’s Ron Fimrite in his 1975 retrospective on the game.

“On offense they roamed like prairie dogs, switching positions to meet changing situations… On defense the Indians played a combination zone and man-to-man that their coach, John Bunn, called a ‘team defense.’ Here again, switching positions was perfectly acceptable. To Eastern audiences, it all smacked of anarchy… And those who watched them shooting one-handed during practice were moved to laughter… ‘I’ll quit coaching if I have to teach one-handed shots to win,’ snapped Nat Holman, the City College of New York coach and the ranking savant of Eastern basketball. ‘They will have to show me plenty to convince me that a shot predicated on a prayer is smart basketball. There’s only one way to shoot, the way we do it in the East— with two hands.’”

No one epitomized Stanford’s unorthodox style more than its star, Hank Luisetti, the team’s most liberated freelancer. On one possession he might bring the ball up the court, the next, play the post, and then later move to the forward position switching from left to right and back again at will. What astonished New York fans was not so much that he shot, rebounded, dribbled, passed and played defense better than anyone on the court, but that he performed these things in unconventional ways. He dribbled and passed behind his back, and appeared to shoot without glancing at the basket. When he drove, he soared like a hawk, looking left and right before releasing a mid-air, one-handed “push” shot.

As a freshman during the 1934-35 season, he averaged better than 20 points a game. In his first varsity appearance as a sophomore, he tried nine shots against the College of the Pacific and sank them all. Later that season he scored 32 points in 32 minutes in the opening game of the conference championship series against Washington. In the next playoff game, he scored 24 of his 30 points in the final 11 minutes to rally Stanford to a 51-47 victory over USC. This was an era when teams rarely scored more than 45 points in a game. For an individual to repeatedly amass 20 or more points per game was extraordinary, the stuff of legend.

But could Luisetti and his freakish style stand up to team like LIU on a national stage?

A crowd of 17,623, the largest of the year, jammed into Madison Square Garden to find out. Halfway through the first half they had their answer. The score was tied 11-11 but it was already apparent that LIU was bewildered by Stanford’s “team defense,” fast break, and Hank Luisetti who seemed to be everywhere, stealing the ball, passing with dizzying accuracy, and lofting his running one-handers from every angle. When Stanford left the court with a 22-14 halftime lead, the fans awarded them a standing ovation.

The second half was no contest. Paralyzed by Luisetti and the freelancing Indians, LIU went a full seven minutes without scoring. Luisetti was in complete control of the tempo, leading all scorers with 15 points as Stanford eased to a 45-31 victory.

The cheering New York fans sensed they had just witnessed a revolution. “Wait a second,” they seemed to shout, “you mean there’s another way to play this game?”

NY Post sportswriter Stanley Frank answered the following day: “Overnight, and with a suddenness as startling as Stanford’s unorthodox tactics, it has become apparent that New York’s fundamental concept of basketball will have to be radically changed if the metropolitan district is to remain among the progressive centers of court culture in this country. Every one of the amiable clean-cut Coast kids fired away with leaping one-handed shots which were impossible to stop.”

Not only was LIU’s long reign over but, more significantly, so was Eastern-style basketball. Luisetti’s running, one-handers had exposed its limitations, inviting coaches to replace their pre-ordained, scripted patterns and two-handed set shots with the spontaneity of player initiative, fast breaks, and running one-handers.

One year later, on the heels of a 50-point performance against Duquesne in Pittsburgh, Luisetti returned to NYC where he led Stanford to another big-time victory in the Garden, this time against Nat Holman’s CCNY squad. Later that season, on March 5, 1938, he broke the national collegiate four-year scoring record against Pacific Coast Conference rival, California.

Luisetti’s heroics, of course, coincided with the elimination of the mandatory center jump after each score. This effectively put more “game time” back on the clock and combined with Luisetti’s unique shooting style transformed basketball into a game of fluidity and grace that rewarded speed and agility as well as strength and size. Years later, Hall of Fame coach Pete Newell chronicled the impact:

“Luisetti’s success opened up new avenues of basketball thinking. It began the trend for faster play. It resulted in fast-break strategy and its possibilities…Defense was sacrificed for increased offense…Where a total of thirty points could at one time reasonably assure victory, it became evident that even fifty points could not guarantee victory… Prior to the advent of Luisetti and his famous one-hand shot… the general thinking among coaches that this was a risky, poor percentage shot. Few coaches allowed their boys to use the one-hand shot, and few boys attempted it because of possible consequences if their coach saw them. The success of Luisetti and his remarkable scoring feats became a national topic and revitalized the thinking of many coaches as to the possibilities of the shot.

Even entrenched conservatives like Nat Holman who had claimed they would never permit one-handed shooting soon became advocates.

Kenny Sailors’ Vertical Jump Shot

While Hank Luisetti was cementing his legacy in Madison Square Garden, a boy ten years his junior was improvising his own version of one-handed shooting on an isolated ranch in southeastern Wyoming. His name was Kenny Sailors and unlike Luisetti who decided to shoot or pass the ball after he was airborne, when Kenny left his feet, it was to shoot.

He remembered the first time he tried it. It was May, 1934 and he was a skinny 13-year-old playing a game of one-on-one with his older brother, Bud, on the makeshift court where they spent their free time. The ground was dirt, the ball was leather with laces, and the rim was a rounded piece of pipe attached to a windmill. Kenny was dribbling this way and that, trying to find a path to the basket, when Bud, not only older but at 6’5” nearly a foot taller and a budding high school star to boot, began taunting him. “Let’s see if you can get a shot up over me.”

“I had to think of something,” Kenny said in an interview a lifetime later. So, he improvised.

He drove to the basket, stopped on a dime, but instead of planning his feet to begin the traditional two-handed set shot he knew with certainty Bud would swat away, he leapt – straight up – and at the apex of his jump with the ball cradled in his right hand and his right elbow aimed at the basket, released it. “I don’t remember if that shot went in or not, but Bud said, ‘Kenny, that’s a good shot. You should keep working on that.’ So, I did.”

Four years later Sailors was a champion miler, long jumper, and a basketball star at Laramie High School, building the leg power that would eventually give him, by his measure, a 36-inch vertical lift — an invaluable asset for a 5’10” guard who liked to shoot jump shots. He led the Laramie to a state championship and followed his brother to the University of Wyoming, also on a scholarship.

Like Hank Luisetti, Sailors’ defining moment came in Madison Square Garden with a brilliant shooting and dribbling performance that earned him “outstanding player” honors in the 1943 NCAA victorious title game against Georgetown. “His ability to dribble through and around any type of defense was uncanny, just as was his electrifying one-handed shot,” the New York Times wrote. Later, on April 1st,Wyoming was anointed the nation’s best college team after defeating St. John’s, the National Invitation Tournament champion, in an overtime Red Cross fund-raising exhibition at the Garden. “The dynamic Ken Sailors,” as the Times put it, “led the way again.”

Were Luisetti and Sailors the first to shoot the ball while airborne?

There’s no way to really to know. There may have been dozens of kids shooting jumpers like Sailors on their barnyard courts, driveways, or local gyms, or hurling down the floor like Luisetti and freelancing in the air.

But only Sailors and Luisetti made it to New York’s Madison Square Garden in big time games in front of thousands of fans and covered by newspapers with a national reach. Together they gave airborne, one-handed shooting full legitimacy and currency, accelerating its prominence and acceptance, and irreversibly changing how basketball was played.

Of the two, Sailor’s vertical jumper was truly transformative, delivering the greater long-term impact.

Luisetti’s running push shot was uniquely personal, hard to replicate, driven by “a body in motion.” In Luisetti we have a freelancer in the open floor leaving his feet as he nears the basket to pass or to shoot, either choice propelled by his forward movement in the air. The closest we get to this technique in today’s game is the “floater” in which the forward motion of the body in flight generates the soft push to the basket. And while Sailors’ first attempt also came at the end of a dribble drive – he was playing one-on-one with no one to pass to or to receive a pass from – his technique did not rely on a dribble or running motion. He jumped vertically. In a game of two-on-two or more, such a shooter could “catch and shoot” from a standing position and do so much quicker than those shooting traditional two-handed set shots. In fact, he had multiple options: catch and shoot; cut, catch and shoot; catch, fake, and drive; catch, fake, drive, and pull-up.

Most importantly, Sailor’s jump shot could be standardized, its mechanics defined, taught, and honed by all players in the same way. You didn’t have to be a modern version of Hank Luisetti – think Pistol Pete – to become a proficient jump shooter in the Kenny Sailors mode.

The nature of the Sailors’ jumper was captured dramatically in this 1946 photograph by Life Magazine photographer Eric Schaal who caught Sailors airborne from his courtside perch in Madison Square Garden.

Note the mechanics. Sailors is suspended two or more feet above the hardwood and at least that much over the outstretched hand of his hapless defender. The ball is cradled above his head, his elbow at 90 degrees, his right hand poised to release the ball along a high arch toward the rim with a snap of his wrist.

“That’s today’s classic jump shot,” John Christgau wrote in his book on jump shooting, The Origins of the Jump Shot. His view was echoed by Jerry Krause, the retired research chairman of the National Association of Basketball Coaches who concluded that Sailors was the first player to develop and consistently use that style of shooting, and by the late Ray Meyer, venerated former coach of DePaul University, who assured Sailors in a handwritten letter, “You were the first I saw with the true jump shot as we know it today.”

Schaal’s photograph, appearing in one of America’s most widely circulating magazines of the era, made an impact from coast to coast. “A shot whose origins could be traced to isolated pockets across the country — from the North Woods to the Ozarks, from the Appalachian Mountains to the Pacific — was suddenly by virtue of one picture as widespread as the game itself,” wrote Christgau. “Everywhere, young players on basketball courts began jumping to shoot.”

That ends our history lesson. In Part 2 we’ll draw some conclusions and begin answering the question before us.

Glad to see you are back from your hiatus!

Thanks, Mike!