Let’s go back.

In fact, let’s go back forty-five years to an era of college basketball retired sports columnist Mike Loprestti fondly remembers.

“There was no shot clock, no three-pointers and no complaints about lack of scoring. Jacksonville put up 109, 104, 106, and 91 points on its way to the 1970 championship game that it lost to UCLA. Who knew that the more they put in rules friendly to the offense, the lower the scores would go?”

That same year I sat on the Notre Dame bench as the Irish student trainer and witnessed first-hand that historic tournament game I referenced in my last post. The one in which Austin Carr set the single-game tournament scoring record, garnering 61 points against Ohio University in the first round of the 1969-70 tournament.

Today, captured on ancient video tape, the game is not only great fun to watch but is of historic interest as it marks the beginning of the end of one era in college basketball and the launching of the one we now experience. In many ways, it foreshadows what the game was to become and how it began to deteriorate even as it grew in popularity driven by 24/7 cable coverage and the explosion of March Madness. Here’s a quick rundown of what the game tape reveals:

• There is only one announcer – Curt Gowdy. There are no color commentators or basketball “experts” providing analysis during the game, at halftime, or after the game. Gowdy is on his own.

• There are very few time-outs and not a single camera shot of either coach prowling the sideline, barking instructions to his players. In fact, there is no film evidence that either coach ever leaves his seat on the bench. Gowdy mentions ND’s Johnny Dee twice and the Ohio University’s Jim Snyder once.

• There are no more than two assistant coaches on either bench and except for one momentary view of Carr approaching the sideline when time is called, there are no television shots of players and coaches huddled during the timeouts.

• The game is extremely fast-paced, driven by the ND’s fast-breaking style of play. On average Notre Dame shoots the ball within 9.75 seconds of each possession, usually after one pass. Twenty-three times the Irish shoot the ball within 5 seconds of taking possession and on only three possessions do they take more than 20 seconds to take a shot. The longest ND possession resulting in a field goal attempt is 25.3 seconds, nearly 10 seconds less than what today’s 35-second clock permits or more accurately, invites.

• There is no dunking as it was made illegal several years earlier in response to Lew Alcindor’s dominating presence. Consequently, the players are adept at using the backboard and either hand around the basket. Carr, in particular, frequently plays the ball off the glass from midrange distance.

• Both teams utilize a style of man-for-man defense popular in the 1950’s and 60’s – similar to today’s “Pack Line” or “Gap” defense. Generally they permit perimeter passing and sag into the lane to block cutters and drivers; but they do not employ the aggressive on the line, up the line denial style of man defense that Bobby Knight popularized in the mid-1970’s. In fact, only one player seems schooled in the hand and footwork tactics seen in contemporary denial defense. There are few double teams and help rotations.

• When pressed, Notre Dame aggressively attacks, scoring more than 30 points in the final ten minutes of play.

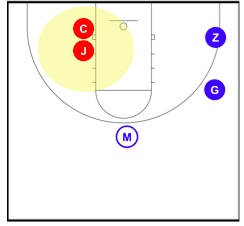

• To compliment its fast break, ND utilizes a “stack” or two-man isolation scheme, an offense similar to Tony Bennett’s Motion-Blocker attack, but one without set plays and multiple ball reversals. It relies solely on read-and-react, freelance movement, the players making all of the decisions. Throughout the season the Irish have employed a double stack formation, but for the tournament they employ a single stack featuring their two most potent threats – Austin Carr and Collis Jones – aligned on the left block. The remaining players placed on the other side of the floor, at the wing and corner.

This creates lots of room for Carr and Jones to maneuver and isolates the defenders from one another, making it difficult, if not impossible, for them to help one another with hedges, traps, and rotations. Notre Dame’s attack strategy is simple and direct: Here’s the attack alignment. Read the defense and play basketball. Once they set their strategy in motion, the coaches stay out of the way.

When Ohio shifts to a box-and-one defense hoping to stop Carr, ND counters with its traditional double stack alignment, separating Jones and Carr in the process. This simple change creates a 2-on-1 advantage on Jones’ side of the floor and Ohio quickly reverts to its man defense. Notre Dame implements its adjustment with a simple voice command from the sideline. There’s no break in action, no timeout, no change in the essential freelance movement of the players.

• Very few of the game’s 184 shot attempts come from modern three point range. The vast majority of the 194 points scored by both teams are made “at the rim” or from true midrange distance: 12’ – 15’ feet from the basket.

• Notre Dame’s ends the game with an offensive efficiency rating of 1.30 – 112 points in 86 possessions. (Incidentally, over the course of two Austin Carr-led seasons, the Irish averaged 78 field goal attempts per game, scoring 90 or more points 33 times, including 18 games of 100 or more, and generating a two-year offensive efficiency rating of 1.18 in the process. High scoring games for them and many teams were the norm.)

Like artifacts unearthed during an archeological dig, these observations tell us a lot about the nature of college basketball “back then.” More importantly, when placed side by side with the experiences, events, and data of the last forty-five years, they suggest the evolutionary path the college game has taken and help explain the troubling nature of today’s game. Six conclusions emerge.

First, the decline in pace and scoring is more severe and longer in duration than most commentators cite.

Second, the decline started in the college ranks and migrated to the NBA. Efforts to reverse the decline moved in the opposite direction.

Third, rule changes to increase “freedom of movement” and “open the floor” have been helpful but have not sufficiently addressed the core problem plaguing college basketball – control freak coaches.

Fourth, the explosion of television coverage epitomized by ESPN and the rise of March Madness nationalized the game, helped standardize instruction, and dramatically popularized college basketball, but in the process, mythologized the role of “the coach” as the networks searched for an enduring, enticing narrative to exploit.

Fifth, though well intentioned, the introduction of the shot clock and the three-pointer reinforced the shifting emphasis from “player” to “coach” and, correspondingly, from “freedom” to “control.” Scoring dropped accordingly.

Sixth, the analytics revolution further cemented the primacy of the coach and led to a mind-numbing sameness in offensive strategy.

In future posts I’ll explore each of these findings in greater detail.

Of course I’m fascinated by these last two posts. I am sharing them with my 76 yr old father who has followed basketball since the days of the Dixie Classic. We talk almost every day about basketball…his secret religion (50 yrs a Baptist Minister;)…and we always come back to this topic. I am following it with GREAT interest.

I also coach, of course, and after watching the Tourney I kept thinking…why not just create mismatches and let the defense adjust? In pick up that’s what I do. Find the mismatch and exploit it until they adjust. Seems like the Stack / Double Stack does that. Know of any resources on the double stack? Thanks for what you’re doing. Great stuff!

Thanks again for your interest. I will be developing an in-depth piece on the stack offense later on. Its genesis lies in the famous Cincinnati Swing and Go offense from the early ’60s.

Pingback: Records are made to be broken, but… | better than a layup