The emergence of Kenny Sailors’ vertical, one-handed jump shot in 1943 and its widespread adoption by the early 1950s is a prism through which we can trace the evolution of shooting styles, their impact on offensive and defensive strategy, and begin to answer the question posed at the start of this essay: Why is a jump shot better than a layup?

The progression of shooting styles over basketball’s first sixty years is not a neatly sequenced timeline in which all players were shooting the same way in one decade and a different way in the next. The progression was, in fact, uneven with thousands of players in different sections of the country shooting in different ways at the same time depending on the peculiar traditions of their own locale, the influence of its coaches and star players, and the frequency of intersectional play, if any, that might expose them to other shooting styles.

As noted in Part I, Ned Irish’s famed extravaganzas in Madison Square Garden helped break down this regional emphasis by bringing the nation’s top teams and players to NYC to play one another. WWII dramatically accelerated the process with GIs from all points of the country – coaches as well as players – playing one another in pick-up games and in formally organized tournaments sponsored by the various military services, exposing them to jump shooters like Hank Luisetti and Kenny Sailors. After the war the GI Bill sent thousands of these returning troops to college campuses around the country, further nationalizing how basketball was played. By the early 1950s, one style of shooting – the Sailors’s vertical jumper – was fast becoming the norm at all levels of play.

Uneven and irregular though it was, if you were to unpack and sequence the various shooting styles in their natural, logical progression, the evolutionary path of shooting is quite clear: generally, two-handed set shooting spawned one-handed set shooting which in turn gave way to the moving or running one-handed push shot pioneered by Luisetti, closely followed a short time later by Kenny Sailors’ vertical jump shot.

Each step in the evolution, the dominant style of shooting affected the offensive principle of “separation.”

All offenses, from basketball’s beginning in 1891 to the present day, whether deliberate or fast, scripted or freelanced, seek to create separation for the shooter. That is, time and space to shoot with as little inference from the defense as possible. To shoot effectively, you have to get free.

Before jump shooting became common in the early 1950s, half court offenses generally required intricate passing and cutting in set patterns and weaves to free a player for an uncontested layup or time enough to attempt a set shot from the perimeter.

Recall our description of Doc Carlson’s Figure 8 weave in Part I: a continuity offense moving all five players through the front court along one of three different pathways or in combination with one another: crosswise beginning with a guard-to-guard pass; vertically with passing between a guard and a forward; or diagonally by passing and cutting players from one corner to the other. In each pattern, the initial pass was made to a player who had moved away from the basket to gain separation from his defender.

For example, examine Carlson’s crosswise pattern. The intended receiver of the initial pass has either advanced up the floor and taken position in the front court where his defender grants him separation because he is not viewed as an offensive threat; or he has taken his defender toward the basket, then quickly reversed direction to free himself to receive the entry pass.

The passer then cuts, looking for a return pass, and is replaced in the pattern by a teammate cutting to his vacated position, and the pattern repeats itself.

This pattern of cutting and replacing continues as the ball moves from side to side until the defense breaks down and a shot opportunity presents itself. For instance, in the process of replacing #1’s spot in the formation, #3 might quickly change direction, breaking behind his defender to receive the pass for a drive to the rim. Or perhaps the ballhandler abruptly changes the pattern, shifting from the crosswise to the vertical scheme, this time catching #5’s defender napping, leading to a two-handed set shot.

In both cases, the offense breaks the pattern’s continuity to separate a particular player from his defender. In one case, for a layup, in the other, a set shot. In effect, the constant cutting and passing lulls the defense to sleep. In Carlson’s crosswise and vertical patterns, it took ten passes and thirty cuts to return every player to his starting position in the continuity. Put them together in the same possession and you double the counts.

Great patience and disciplined ballhandling was required to sustain such pattern long enough to create separation, especially for a two-handed set shot that, by definition, features a stationary shooter, balanced with both feet on the ground, dependent upon his teammates to pass him the ball at just the right time. In other words, he can’t create the shot on his own off a dribble drive or by out-maneuvering his defender for a quick catch and release because the set shot by its very nature is not quick. To ensure accuracy, coaches insisted that the shooter first “set his body” like a rifleman using his sling, arms, and legs to create a stable platform from which to aim and fire his weapon. If he didn’t have time to do this, he was forced to dribble or pass the ball to a teammate to re-trigger the sequenced pattern of cutting and weaving.

Here’s a short clip of two-handed shooters at work.

The one-handed set shot emerged first on the Pacific Coast. It required the same stable base as its two-handed cousin but was a bit quicker to execute and was less cumbersome in a mechanical sense as there was only one hand involved in the shooting motion. Over time it replaced the two-handed set shot as the preferred method of perimeter shooting. I don’t have game film of the one-handed set shot but it’s easy for most fans to visualize as its basic form lives on today in free throw shooting.

With the advent of Luisetti’s airborne, one-handed push shot, separation occurred much quicker as it didn’t require time to create the stationary base needed for effective set shooting. Nor did it rely on a perfectly timed pass to the shooter as he was completing his “set up.” Instead, Luisetti’s own forward motion, usually off a dribble, generated the shot. Unfortunately, there’s no game footage of his transformative performance in Madison Square Garden in the mid-1930s but there are old film clips of shooters copying Luisetti’s style in the years that followed, plus more recent footage of today’s “floater,” a close relative of the original push shot.

Instead of setting themselves for the obligatory two-handed or one-handed set shot, each of these shooters is “on the run,” pushing the ball up and toward the basket with one hand after taking flight. In many ways, this shooting style is more indicative of unscripted freelance play than of shooting itself, and was perhaps Luisetti’s key contribution to the game. Combined with his flashy behind-the-back dribbling and passing, his running jumper challenged the coaching orthodoxy of the day, popularizing a quicker, freer form of play, and demonstrating that his style of shooting did not depend upon intricate teamwork but could be achieved by a player maneuvering on his own to gain separation.

As the evolution of shooting styles progressed from one to the next, the time needed to achieve separation shrank while the resulting options to attack the defense increased.

Clearly, one’s foot and hand speed affect how quickly a shooter can free himself from his defender to attempt a shot, but the mechanics required to execute a specific style of shooting plays a critical role, too. For example, as we have seen, a two-handed set shooter is frozen in place, hoping to complete his shot but if denied, forced to make a return pass to one of his teammates or to shift from a shooting stance to a dribbling posture to initiate the next step within the offense. The one-handed set shooter can accomplish this more quickly as the ball is already cradled in one hand and positioned for either shooting, passing or dribbling. Moreover, his feet are not likely anchored to the floor in the parallel position favored by two-handed shooters, but are in a staggered position mirroring his shooting hand. This posture makes it easier and quicker to convert from a shooting intent to passing or dribbling. Luisetti’s shooting style, of course, speeds the process further as the shooter frees himself by leaping past his defender, deciding to shoot or pass while in the air.

This progression of quicker separation and increasing options for attacking the defense culminates in the vertical jump shot pioneered by Kenny Sailors.

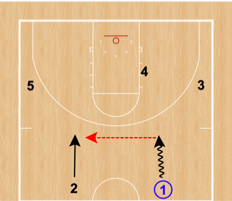

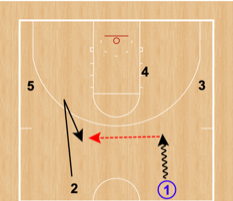

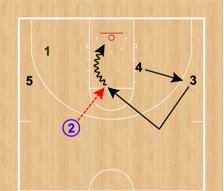

As noted in Part I, like Luisetti’s push shot, Sailors’ jumper often came off the dribble. For example…

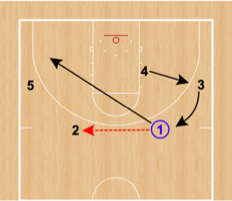

But the vertical nature of Sailors’ jumper didn’t require a dribble to spring him loose to initiate the shot. Instead, a shooter using his approach could maneuver without the ball to create separation, then as he received a pass with his dribble still live, attack the defense in multiple ways:

• catch and shoot from a stationary position or off a cut or screen

• catch, fake the shot, and drive to the rim

• catch, fake the shot, drive, and pull-up for a jumper

In each case, the speed at which he could convert the pass into a shooting motion by beginning his jump or by merely threatening the jump put the defense at extreme risk.

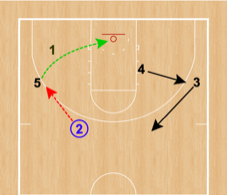

In quick succession, here are a series of films featuring shooters from the across the decades executing each maneuver. First, the catch and shoot from a stationary position.

Second, the catch and shoot off a cut or screen. As you watch, focus in particular on the film’s first three clips featuring Andre Battle, a relatively unknown player from Loyola Chicago in its 1985 Sweet Sixteen game against defending national champion, Georgetown. Mentally compare the rapid speed at which he moves, catches, and shoots with the deliberate, slower pace of the two-handed set shooters featured in our earlier film. In many ways this comparison encapsulates the dramatic impact of Sailors’ shooting technique on how basketball has been played since the early 1950s.

Next, the catch, shot fake, and drive to the basket.

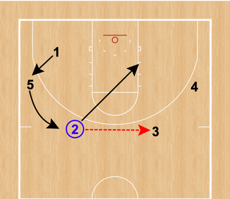

And lastly, the catch, shot fake, drive, and pull-up jumper. No maneuver more effectively epitomizes modern basketball than the pull-up. The analytic community tends to disparage it but with the exception of the traditional big man — think Kareem or Wilt the Stilt — all great players master it.

The traditional set shooters of basketball’s early decades were hampered by their flat-footed stationary position. Shooters in the Luisetti mode were quicker and stealthier, but depended on the forward motion of the dribble drive to launch their airborne push shots. Once in motion, the die was cast; there was no turning back. But Sailors’ jump shot didn’t commit the shooter prematurely. He retained multiple options for launching the shot, moving from one to the next, quickly and seamlessly as he read the defense.

Sailors’ Impact

Hall of Fame coach Ralph Miller believed that Sailors’ jump shot served as the catalyst for the last major revolution in basketball:

“The jump shot forced defensive minds to re-evaluate their position in the game because the old theories could not contain the new weapon. Until the 1950’s, offense had always been allowed the privilege of initiating and controlling action on the floor. It always attacked first, while the defense waited to see the attack start before reacting to the scoring thrust. This friendly and unwritten agreement worked nicely for both parties until the jump shot appeared on the scene… Old methods for one-on-one coverage with help were no match for the jump shooter… The jump shot threatened the balance of power between the two primary elements of the game, offense and defense.”

Once Sailors’ vertical jumper became the norm, it changed basketball in four ways.

First, the court got “bigger.” In recent years NBA coaches have used the term gravity to describe the impact the three-point shot has on defense; that as shooters get more proficient from spots beyond the three-point arc, they “pull” defenders with them, stretching the defense and opening paths for driving. The defense is forced to guard more space. But as we’ll explore in Part III, this was true long before the advent of the 3-pointer. Whether a jump shot is worth three points or two, the shooter’s range and quickness create gravity, making the court “bigger” and harder to defend.

Second, defensive reaction time got shorter. Reaction time is the time it takes for one player to react to the movement another player. To succeed in basketball, you just have to be quicker than your opponent at a particular moment in time. For example, how long will it take for a defensive player to react to the movement of an offensive player and adjust his position accordingly? The answer depends on the distance between players and their relative quickness. In order to react in time, the defensive player must create a cushion – a position that allows him to pressure the ball yet protect the basket.

The speed and flexibility of the jump shot dramatically shortened defensive reaction time. Between players of equal ability, generally the offensive player will get the shot he wants. To defend against a good jump shooter his defender must play tighter and thus is more susceptible to a shot fake and subsequent drive, or to the pull-up jumper if he is able to recover in time to stop the drive.

Third, standard defenses were forced to change. When playing man-to-man defense in the era before the jump shot, it was possible to sag or loosen up on a ballhandler when he dribbled. Now he could stop and shoot right out of the dribble. And a player without the ball could immediately “catch and shoot” as he received a pass. As a result, a defender was forced to play much tighter than before. This, in turn, made it imperative that he have help when he was outmaneuvered because of his aggressive play. When picks and screens were involved, it became even more difficult to guard the individual opponent.

Similarly, zone defenses became vulnerable. The placement of the defenders in a zone choked off paths to the basket forcing opponents to shoot from the outside. It collapsed around the pivot area disrupting the pivot offense. It was of value as long as the opponent was attempting to get to the basket. But uncovered jump shooters outside the perimeter of the zone, armed with greater range, speed, and accuracy than the game’s traditional set shooters, rendered the standard zone obsolete.

In response, coaches turned to a variety of new defensive strategies: full-court man, zone, and combination presses to create fatigue and confusion; half court disruptive tactics involving aggressive trapping, help side positioning and various rotation rules; combination defenses like the matching zone and “junk” defenses such as the “box and one” and “triangle and two.” Anything to seize initiative from the offense.

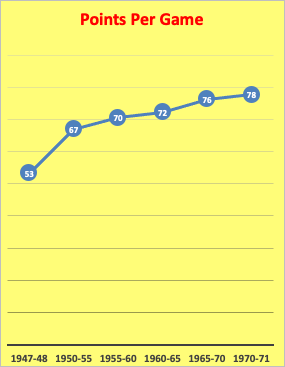

Fourth scoring rose dramatically because the speed at which jump shots could be taken generated more shot attempts, leading naturally to more baskets. During the 1947-48 season, the first for which the NCAA kept uniform statistics, college teams averaged 53 PPG. Twenty-four seasons later, in 1970-71, the per-game scoring average had increase by 25 points to

78 PPG. Shooting percentages climbed as well from 29% to 44% because the mechanics of the jump shot were more efficient and easier to master than traditional set shooting.

In two-handed set shooing, though the shooter’s feet remain on the floor, he uses knee and hip extension to push his body upward and typically releases the ball before the vertical body motion ceases. Thus, his upward body motion contributes to the ball’s release speed, angle and backspin. Add proper placement and coordination of two hands to the equation and it takes exquisite timing to make the shot with any consistency. One hand off-kilter, exerting a tad too much pressure on the release, and the ball flies off target.

The jump shot has fewer moving parts. The release typically occurs at the peak of the shooter’s jump and is produced largely by the motion of the shooting arm and the follow-through generated by his cocked wrist because the body has lost all or most of its velocity at that point. He’s literally hanging in the air, the ball rolling off his fingertips in a backward motion that creates backspin and a softer touch.

And it wasn’t just the shot’s speed and mechanical ease that produced more attempts and makes, but the fact that every player on the floor became a jump shooter. It was an equal opportunity weapon, a standard way of shooting available to all. Short or tall, quick or slow, regardless of position, everyone could master its fundamentals and use it as a shooting technique.

Before Sailors jumper became prominent, shooting styles were largely determined by the position you were assigned: hook shots and “turn” shots by the center in the short and midrange post area; one-handed or two-handed set shots from the perimeter by guards and forwards; and layups, tip-ins, and put-backs for anyone who could get close enough to the basket.

With the jump shot, any player could generate shots from anywhere on the floor, limited only by his personal ability and physical traits. Standardization led to frequency and frequency to proficiency.

Why is a jump shot better than a layup? We’ve laid the groundwork… we’re almost there. In Part 3, we finally answer the question.